Analysing the Humanitarian Corridor

As Myanmar’s rebel group Arakan Army took control over most of Rakhine state, including all townships bordering Bangladesh, anticipation of a famine threatening civilians trapped in this ongoing civil war has been doing rounds for quite some time

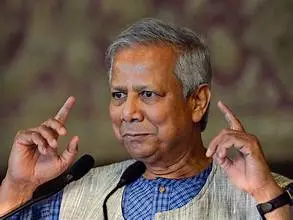

Dr. Muhammad Yunus, the chief advisor of Bangladesh’s interim government, has been facing flak over the recently proposed humanitarian ‘corridor’ connecting Bangladesh to Rakhine state in Myanmar.

As Myanmar’s rebel group Arakan Army took control over most of Rakhine state, including all townships bordering Bangladesh, anticipation of a famine threatening civilians trapped in this ongoing civil war has been doing rounds for quite some time.

In this context, the interim government justified the proposed humanitarian ‘corridor’ connecting Bangladesh’s Cox Bazar to Rakhine that would facilitate aid delivery to civilians trapped in war-torn Rakhine. This comes at a time when the country is grappled with political uncertainties and growing complexities that contributed to weaning popularity of Dr. Yunus. In 2017, about 600,000 Muslim Rohingyas fled to Bangladesh from their homes in Rakhine state in Myanmar to escape military persecution and armed violence, a crisis that has been internationally recognised as a humanitarian catastrophe. Presently, Bangladesh hosts the largest number of Rohingya refugees, about 1.2 million, predominantly in Cox Bazar district bordering Myanmar’s Rakhine.

The repatriation of Rohingya refugees, a long-standing (and contesting) issue, has gained renewed attention under the Yunus-led interim government.

The ‘corridor’ controversy started in early April when chief adviser’s high representative for the Rohingya issue Khalilur Rahman remarked of a UN-brokered talk between the interim government and the rebel Arakan Army (that agreed to take the Rohingyas back), in efforts of establishing a ‘humanitarian channel’ connecting Bangladesh to Rakhine, which the interim government stated to consider.

This triggered sharp reactions from political parties—Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), Islami Andolan, Communist Party of Bangladesh (CPB), National Citizen’s Party (NCP), People’s Rights Council, Jamaat-e-Islami, and even non-political party Hefazat-e-Islam—criticising this decision to risk infringing on nation’s sovereignty, territorial integrity and security and demanding for its suspension.

Apprehensions were raised on the actual intent behind such a corridor, suspecting it as Yunus patronising interests of foreign nations, while condemning the interim government for taking an unilateral decision (which it is not constitutionally authorised with) without any consultation with political parties. Even the Bangladesh Army chief expressed his disapproval for such a humanitarian ‘corridor’, rejecting any such ‘bloody corridor business’.

Since early this year, Yunus-led interim government has been pushing the issue of repatriation of Rohingyas, although seeing no progress. It is believed that the idea of humanitarian ‘corridor’ was first broached during Yunus’s New York visit last September.

This February, replying to Yunus’s letter, UN chief Antonio Guterres acknowledged Dhaka’s concern on Rohingya crisis and assured engagement “…. to enable safe, rapid, sustained and unhindered humanitarian access to those in need in Rakhine and throughout Myanmar.” However, Guterres’s visit to Cox Bazar in March is particularly noteworthy for during this visit the idea of humanitarian ‘corridor’ was first voiced. Recognising the challenges of refugees living in Bangladesh camps due to the declining humanitarian aid for Rohingyas (that led to UN’s initial decision to reduce budget for food allocation for Rohingyas, later halted after Guterres’ visit) and the situation of return of Rohingyas to their homeland to be ‘extremely difficult’, Guterres suggested the idea of a humanitarian channel from Bangladesh ‘if circumstances allow’ which would require ‘authorisation and cooperation.’

Moreover, a joint pledge of repatriation of Rohingyas by ‘next Eid’ (that is, June) was announced by Muhammad Yunus. Meanwhile, the chief advisor has been actively engaged in diplomatic efforts (EU, US, Australia, Sweden, Japan, China, UN) to secure international aid and support for repatriation of the Rohingya refugees.

Many issues surrounding the Rohingya issue are already stake take for Dhaka. First, the rebel militant group Arakan Army’s significant control of Rakhine in December, triggering severe humanitarian crisis in Bangladesh’s bordering region. Second, the persistent issue of influx of Rohingyas in Bangladesh from Rakhine amid international aid challenges in Bangladesh Rohingya refugee camps. Third, the violence perpetrated by Rohingya armed groups inside community’s refugee camps in Bangladesh and fourth, instances of abduction of Bangladeshi fishermen fishing in Naf river in Cox Bazaar by the Arakan Army.

Given these challenges perpetuating Bangladesh’s economic and political constraints, the proposal of a humanitarian ‘corridor’, expectedly, has been frowned upon. Humanitarian corridor as a ‘neutral’ space intended to provide a safe passage of refugees and aid in warn-torn regions has, many a times, found to be misused for military exploitation and political manipulation, thus, aggravating humanitarian crisis.

Indeed, the interim government made a miscalculation in agreeing on a humanitarian ‘corridor’. Following the critical reactions of political parties, a change in stance came on the horizon, adding to the controversy. First, the foreign advisor Md Touhid Hossain declined such a corridor to have been a part of discussion during the UN chief’s visit, contradicting Khalilur Rahman’s remark. Instead, the foreign advisor briefed about Bangladesh’s policy decision to set humanitarian corridor ‘in principle’ in Rakhine, under the UN’s supervision, to provide humanitarian aid to Rakhine state in Myanmar.

The Chief Advisor’s Press Secretary then dismissed any discussion with the UN on so-called humanitarian corridor and that such decision will be reached only after discussion with ‘all parties’. Even Khalilur Rahman, the recently redesignated National Security Officer, has now backtracked form his earlier remarks and said there has been no agreement on the ‘corridor’, that there only had been talks of sending aid to Rakhine, and that a humanitarian channel would be pursued ‘if all parties agree’.

The UN Resident Coordinator, in her recent visit to Dhaka, too, now denies of UN’s involvement on talks on any ‘humanitarian corridor’. It is without a doubt that internal pressures on Yunus has a role to play in such change in position—from humanitarian ‘corridor’ to now a humanitarian ‘channel’.

These contradictions have instigated more speculations in Bangladesh of the interim government giving in to foreign interference, endangering the country’s sovereignty. The backlash Yunus faced over his decision to hand over Chattogram port to foreign firm for his unilateral decision that risk the country’s economic independence, further added fuel to the fire, with political parties taking note of interim government’s cosying to policies that undermines national sovereignty.

The chief advisor threw the wrong ball in his efforts to repatriate the Rohingyas. Now, with pressures mounting on Dr. Yunus to conduct election soon announcing a clear roadmap, it remains to be seen if the interim government plays its cards right.

This Article is authored by Dr. Ankita Sanyal, a Research Fellow at International Centre for Peace Studies (ICPS), New Delhi. She can be reached at sanyal_ankita@outlook.com.