Report is an impeachment referral

Washington: There is enough evidence that US President Donald Trump obstructed justice that merits impeachment hearings. That in one sentence, is the most important summary of the redacted version of Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report released on Thursday running to 448 pages.

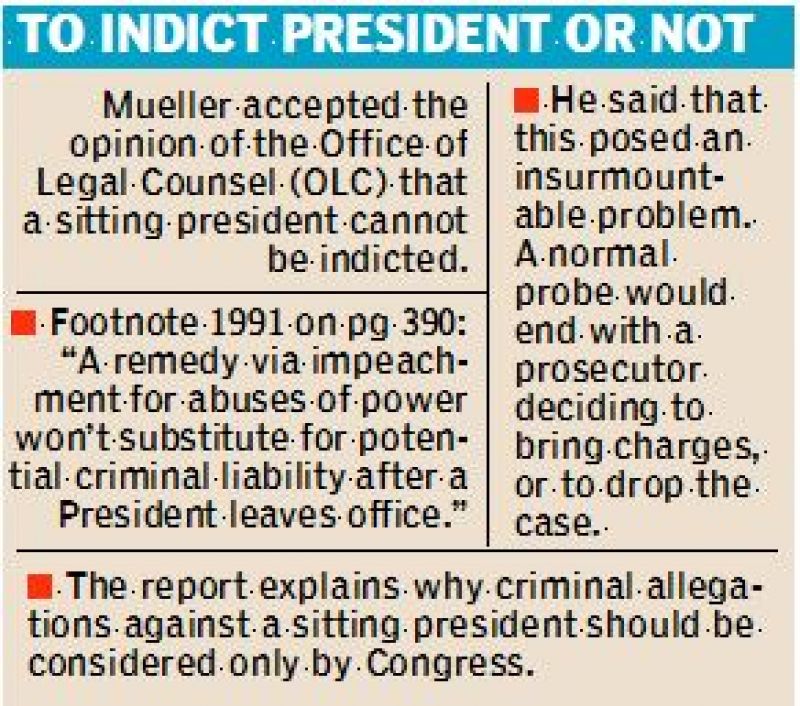

The report in short, could be called an impeachment referral. Footnote 1991 on page 390 of the report states: “A possible remedy through impeachment for abuses of power would not substitute for potential criminal liability after a President leaves office.” However, the report explains why criminal allegations against a sitting president should be considered by Congress and not the Justice Department. That is because in the American criminal-justice system, every accused, no matter how big or small, is entitled to a fair defense and a chance to clear their name.

Mueller explained in detail why he “determined not to make a traditional prosecutorial judgment” as to whether the president had broken the law by obstructing justice. He begins by noting that he accepted the opinion of the Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) that a sitting president cannot be indicted.

That, Mueller explained, posed an insurmountable problem. A normal investigation would end with a prosecutor deciding to bring charges, or to drop the case. It’s a binary choice. But “fairness concerns counselled against potentially reaching that judgment when no charges can be brought.”

Ordinarily, a criminal charge would result in “a speedy and public trial, with all the procedural protections that surround a criminal case.” But if Mueller were to state plainly that, in his judgment, the president had broken the law, it would afford “no such adversarial opportunity for public name-clearing before an impartial adjudicator.” In other words, because a sitting president cannot be indicted, making such a charge publicly would effectively deny Trump his day in court, and the chance to clear his name.

Mueller also pointed to the OLC’s guidance on seeking sealed indictments, which could be unsealed when a president leaves office, or leveling such charges in an internal (and, presumably, nonpublic) report. Secrecy, the OLC counselled, would be difficult to preserve—and so either step could place a president back in the same unfair situation, accused of a crime without the chance to clear his name.

Crucially, the same concerns don’t operate in reverse. If — examining the evidence and the law — a prosecutor were to determine not to charge an individual, there would be no fear that public disclosure of that decision would be unfair. But if Mueller believed he could not fairly say that the president had committed a crime, he also believed he could not honestly say that he hadn’t. “If we had confidence after a thorough investigation of the facts that the President clearly did not commit obstruction of justice, we would so state,” the report explained. While the report does not conclude that the President committed a crime, it also does not exonerate him.

Attorney General William Barr reviewed the same evidence, though, and came to a different conclusion. In his summary of the report, he wrote, “Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein and I have concluded that the evidence developed during the Special Counsel’s investigation is not sufficient to establish that the President committed an obstruction-of-justice offense.”

There is a vital distinction here between the two findings. Mueller wrote that his evidence was not sufficient to clearly establish that the president had not committed a crime; Barr insisted that it was not sufficient to establish that he had. It’s possible to read the two conclusions as different ways of stating the same finding; it’s equally possible to read them as fundamentally at odds with each other.

— Agencies