How Venezuela turns its useless bank notes into gold

EL CALLAO: Venezuela's most successful financial operations in recent years have not taken place on Wall Street, but in primitive gold-mining camps in the nation's southern reaches.

With the country's economy in meltdown, an estimated 300,000 fortune hunters have descended on this mineral-rich jungle area to earn a living pulling gold-flecked earth from makeshift mines.

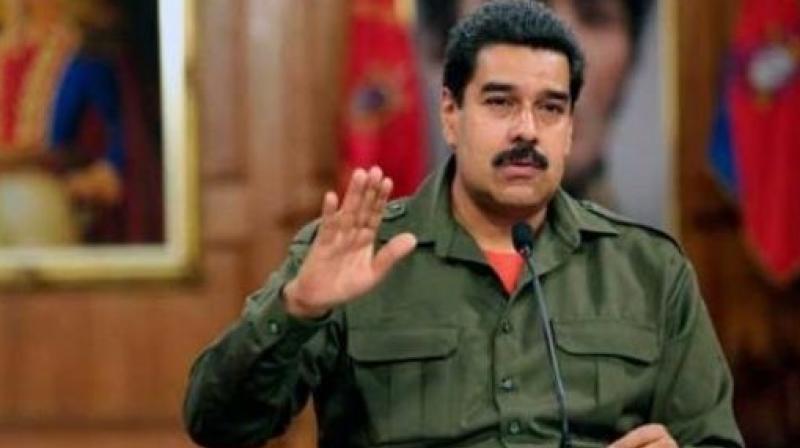

Their picks and shovels are helping to prop up the leftist government of President Nicolas Maduro. Since 2016, his administration has purchased 17 tonnes of the metal worth around $650 million from so-called artisan miners, according to the most recent data from the nation's central bank.

Paid with the country's near-worthless bank notes, these amateurs in turn supply the government with hard currency to purchase badly needed imports of food and hygiene products. This gold trade is a blip on international markets. Still, the United States is using sanctions and intimidation in an effort to stop Maduro from using his nation's gold to stay afloat.

The Trump administration is pressuring the United Kingdom not to release $1.2 billion in gold reserves Venezuela has stored in the Bank of England. U.S. officials recently castigated an Abu Dhabi-based investment firm for its Venezuela gold purchases, and have warned other potential foreign buyers to back off.

The existence of Maduro's gold program is well-known. How it functions is not.

To get a glimpse inside, Reuters tracked Venezuela's gold from steamy jungle mines, through the central bank in the capital of Caracas to gold refineries and food exporters abroad, speaking with more than 30 people with knowledge of the trade. They included miners, intermediaries, merchants, academic researchers, diplomats and government officials. Almost all requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly, or because they feared retribution from Venezuelan or U.S. authorities.

What emerges is the portrait of a desperate experiment in laissez-faire industrial policy by Venezuela's socialist leaders. U.S. sanctions have hammered the nation's oil industry and crippled its ability to borrow. The formal mining sector has been decimated by nationalization. So Maduro has unleashed freelance prospectors to extract the nation's mineral wealth with virtually no regulation or state investment.

The Bolivarian Revolution now leans heavily on ragtag laborers such as Jose Aular, a teenager who says he has contracted malaria five times at a wildcat mine near Venezuela's border with Brazil. Aular works 12 hours daily lugging sacks of earth to a small mill that uses toxic mercury to extract flecks of precious metal. Mining accidents are common in these ramshackle operations, workers said. So are shootings and robberies.

"The government knows what happens in these mines and it benefits from it," said Aular, 18. "Our gold goes into their hands."

Maduro has also received a crucial assist from Turkish President Recep Erdogan, a fellow strongman who has likewise sparred with the Trump administration.

Venezuela sells most of its gold to Turkish refineries, then uses some of the proceeds to buy that nation's consumer goods, according to people with direct knowledge of the trade. Turkish pasta and powdered milk are now staples in Maduro's subsidized food program. Trade between the two nations grew eightfold last year.

But scrutiny is intensifying as Venezuela's politics reach the boiling point. In recent days, many Western countries have recognized Venezuela's opposition leader Juan Guaido as the South American nation's rightful president.

Maduro's adversaries have called on foreign buyers of Venezuela's precious metal to stop doing business with what they say is an illegitimate regime.

"We are going to protect our gold," opposition legislator Carlos Paparoni told Reuters in an interview.

The gold road begins in places like La Culebra, an isolated jungle area in southern Venezuela. Here, hundreds of men labor in crude mining operations that would be at home in the 19th century. They excavate mineral-laden dirt with picks in hand-dug tunnels, hauling it out with pulleys and winches.

Their activity is laying waste to fragile forest ecosystems and spreading mosquito-borne diseases. Miners complain of shakedowns by military forces sent to guard the region, whose homicide rate is seven times the national average. Venezuela's ministries of defense and information did not respond to requests for comment.

Miner Jose Rondon is used to hardship. Now 47, he arrived in 2016 from northeast Venezuela with his two adult sons. His bus driver's salary could not keep pace with Venezuela's hyperinflation, which the International Monetary Fund projects will hit 10 million percent this year.

The three men net roughly 10 grams of gold monthly from backbreaking work. Still it is roughly 20 times what they could earn back home.

"Here I do much better," said Rondon, resting in a crude bunkhouse strung with hammocks.

Gold in hand, miners head to the town of El Callao to sell their nuggets. Most buyers are unlicensed, small-scale traders working in cramped shops fitted with alarms and steel doors.

"The state is buying gold, everyone is buying gold, because it's what is doing well," said Jhony Diaz, a licensed wholesaler in Puerto Ordaz, 171 kilometers (106 miles) north of El Callao. Diaz says he buys gold from traders and resells every three days to the central bank.

Because Venezuela's currency, the bolivar, is worth less every hour someone holds it, the state pays a premium over international prices to make it worthwhile for those who could smuggle gold out of the country to exchange for dollars.

Traders who sell to Diaz end up with bricks of cash to carry back to El Callao and other gold-rush towns to pay miners, who use it to buy food, supplies and send whatever is left to their families.

Gold purchased by the government is smelted in the nearby furnaces of Minerven, the state-run mining company, according to a high-ranking employee. It is then transported to the vaults of the central bank in the capital Caracas, 843 kilometers (524 miles) away.

The gold does not stay there long. The central bank's gold reserves have plummeted to their lowest levels in 75 years. Venezuela is selling the artisan metal as well as existing reserves to pay its bills, according to two high-ranking government officials.

The main buyer these days is Turkey, the officials said.

Maduro's gold program has developed in tandem with his deepening relationship with Turkey's Erdogan. Both leaders have been criticized internationally for cracking down on political dissent and undermining democratic norms to concentrate power.

A Nov. 1 executive order signed by U.S. President Donald Trump bars U.S. persons and entities from buying gold from Venezuela. It does not apply to foreigners. Ankara has assured the U.S. Treasury that all of Turkey's trade with Venezuela is in accordance with international law.

Venezuela in December 2016 announced a direct flight from Caracas to Istanbul on Turkish Airlines. The development was surprising given low demand for travel between the two nations.

Trade data show those planes are carrying more than passengers. On New Year's Day, 2018, Venezuela's central bank began shipping gold to Turkey with a $36 million air shipment of the metal to Istanbul. It came just weeks after a visit by Maduro to Turkey.

Shipments last year reached $900 million, according to Turkish government data and trade reports.

Venezuela's central bank has been selling its artisan gold directly to Turkish refiners, according to two senior Venezuelan officials. Proceeds go to the Venezuelan state development bank Bandes to purchase Turkish consumer goods, the officials said.

Gold buyers include Istanbul Gold Refinery, or IGR; and Sardes Kiymetli Mandele, a Turkish trading firm, according to a person who works in Turkey's gold industry as well as a Caracas-based diplomat and the two senior Venezuelan officials.

In an interview with Reuters, IGR CEO Aysan Esen denied the company has been involved in any Venezuelan gold deals. In a written statement, she said she met with Venezuelan and Turkish officials in Istanbul in April to offer her views on compliance with international regulations.

Esen said she advised the Turkish government that working with Venezuela "would not be right for leading institutions or the state."

As for Sardes Kiymetli Mandele, no one at its Istanbul offices responded to inquiries from Reuters.

Turkish consumer products, meanwhile, are making their way to Venezuelan tables. In early December, 54 containers of Turkish powdered milk arrived at the port of La Guaira near Caracas, according to port records seen by Reuters.

The Istanbul-based shipper, Mulberry Proje Yatirim, shares an address with Marilyns Proje Yatirin, a mining company that signed a joint venture with Venezuela's state mining firm Minerven last year, according to filings with a Turkish trade registry gazette in September.

The companies did not respond to a request for comment.

Even Maduro's critics acknowledge he has pulled off a neat trick of alchemy: By compensating hard-pressed citizen miners with inflation-ravaged bolivars and obtaining precious metal in return, he has found a way to spin straw into gold.

Venezuelan economist Angel Alvarado, an opposition lawmaker, said "dark operations and unusual mechanisms of commercial exchange," are among the few tools Maduro has left.

"There is a desperation to stay in power at all costs," Alvarado said.