Mental health and Indian pop culture

Why does Bollywood repeatedly misrepresent mental health and illness for a general population that is ridden with mental health issues?

Here’s what we know: Indian cinema, especially Bollywood, repeatedly misrepresents mental health and illness. And yet, India is not a country completely in the dark when it comes to mental health awareness. So why does its most popular film industry rarely create content which correctly portrays mental health for a general population that is ridden with mental health issues? It is baffling to see that well-educated and socially aware filmmakers are tempted to exploit certain elements of psychological disorders as critical plot elements, but wrap entire movies, without ever shedding any actual light on a given disorder — like Asperger’s Syndrome in My Name Is Khan, depression in Anjaana Anjaani or autism in Barfi.

Priyanka Chopra and Ranbir Kapoor’s characters suffer from autism in Barfi.

Priyanka Chopra and Ranbir Kapoor’s characters suffer from autism in Barfi.

It is baffling to see that socially aware filmmakers are tempted to exploit certain elements of psychological disorders as critical plot elements, but wrap entire movies, without ever shedding any actual light on a given disorder — like Asperger's Syndrome in My Name Is Khan.

It is baffling to see that socially aware filmmakers are tempted to exploit certain elements of psychological disorders as critical plot elements, but wrap entire movies, without ever shedding any actual light on a given disorder — like Asperger's Syndrome in My Name Is Khan.

MISREPRESENTATION AND MISINFORMATION

If inadequate representation isn’t enough, there is plenty of misinformation thrown our way in terms of the clinical diagnosis, aetiology (causes), prevention, or even care! For example, in Black, Amitabh Bachchan’s character — who is meant to be suffering from Alzheimer’s — is shown to regain his memories. That’s blatantly incorrect, as it is a disorder that progressively worsens, misleading to a general public and potentially harmful, in terms of setting unrealistic expectations. Don’t you think?

Amitabh Bachchan’s character is meant to be suffering from Alzheimer’s in Black.

Amitabh Bachchan’s character is meant to be suffering from Alzheimer’s in Black.

Over the years, although there have been movies which have done a better job at representation as compared to the rest, the attitudes remain the same. Kiran Kotrial, a popular screenwriter, says, “Broadly speaking, there hasn’t been any real change in the representation of mental health in mainstream commercial cinema as words like paagal are loosely used and aren’t yet considered to be politically incorrect.” From normalising discriminatory behaviour, to mocking characters with mental illnesses through supposedly comic roles like in Krazzy 4, to sensationalising psychological disorders, or emphasising the criminality and unpredictability of the mentally ill (like in Darr), or lampooning mental hospitals like in Humshakals... the list goes on.

Kalki Koechlin’s character suffers from Cerebral Palsy in Margarita With A Straw.

Kalki Koechlin’s character suffers from Cerebral Palsy in Margarita With A Straw.

The misinformed usage of umbrella terms like “depression” and “schizophrenia” as explanations to mental illnesses only show the large disparities between a DSM criterion and Bollywood’s distortions. Most movies also fail to show clear distinctions between learning or intellectual disabilities and psychotic disorders, leaving the audience bewildered. Psychiatrists are also ill-represented, with some performing roles of exorcists or encouraging exorcism, like Akshay Kumar in Bhool Bhulaiya, which gives an impression that mental illnesses translate to supernaturalism. Or you have the situation where the reel-life psychiatrists suggest Electro Convulsive Therapy (ECT) in an ominous manner, like Om Puri in Kyon Ki.

Akshay Kumar plays a psychiatrist in Bhool Bhulaiya.

Akshay Kumar plays a psychiatrist in Bhool Bhulaiya.

You might think we’re making a mountain of a molehill and you might cite artistic licence, sure… but don’t think that irresponsible representation doesn’t add to the problem of stigma, as people within the industry are well aware. Fauzia Khan, a Creative Producer, says, “Mental health is still represented in a highly exaggerated fashion with mainly physical manifestations. The Indian audience has a tendency to be influenced by this representation and feel that the sphere is in black and white. Any real de-stigmatisation is possible only if there is a realistic portrayal and characters suffering from mental illnesses aren’t used as caricatures.”

The most recent addition to this atrocity is the upcoming comedy movie Mental Hai Kya which aims to “bring out the crazy in you as sanity is overrated” and that “crazy is the new normal”. Really? At a point where mental health needs utmost attention, it is exasperating to see filmmakers choosing problematic titles that are born from loose, derogatory phrases used in Indian languages.

To top it all, the movie posters make an absolute mockery of self-harm with Rajkumar Rao burning a cigarette on his forehead as he laughs. A pool of ignorance, Indian cinema rarely allows for healthy discussions regarding mental health. By exaggerating mental illness, filmmakers feel that they are able to feed the audience with the right amount of drama, humour and conflict needed to keep them entertained. Mental illness ends up being the excuse for any amount of gore and irrationality shown on screens.

MAKING A DIFFERENCE

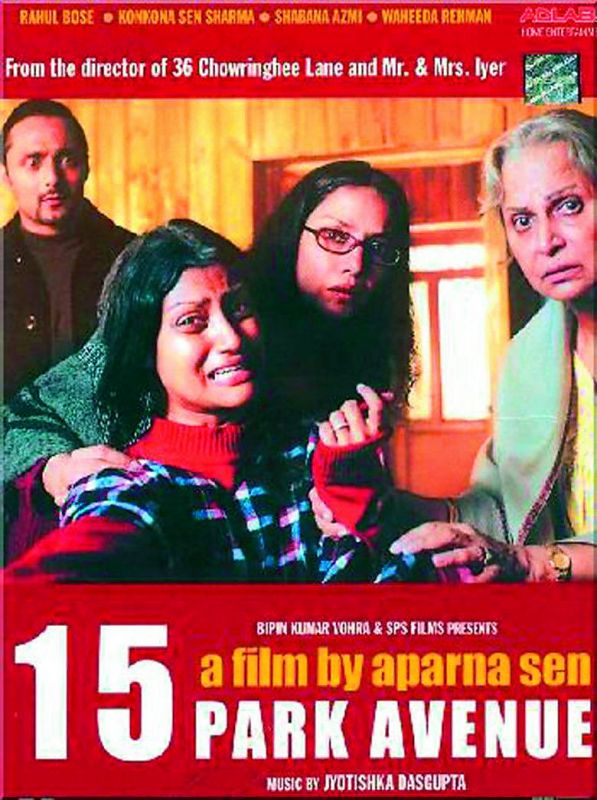

“If our movies, working within the realm of the main storyline manage to convey the pain and experiences of the afflicted person sensibly and interestingly, the audience will surely ‘take home’ some sense and perceive mental health differently and be more sensitised to the travails of one suffering from mental illness,” says Kotrial. Fortunately, there do exist a few movies which show a refreshing change in the manner of which mental health has been dealt with like 15 Park Avenue’s depiction of Schizophrenia or Cerebral Palsy in Margarita With A Straw, or Dear Zindagi normalising therapy. Hichki is a movie adapted from the Hollywood movie Front of the Class which itself was based on the book, Front of the Class: How Tourette Syndrome Made Me the Teacher I Never Had. Hichki finally brings to light a much neglected disorder with the plot revolving around a teacher having Tourette’s syndrome. Although such films deviate from the usual ignorance, they are still few in number and there is much room for growth. Inducing pity in its audience will not help the cause but portraying empowered and functioning individuals with mental issues will.

Rani Mukherjee-starrer Hichki, adapted from the Hollywood movie Front of the Class, brings to light a much neglected disorder with the plot revolving around a teacher having Tourette’s syndrome.

Rani Mukherjee-starrer Hichki, adapted from the Hollywood movie Front of the Class, brings to light a much neglected disorder with the plot revolving around a teacher having Tourette’s syndrome.

Konkona Sen Sharma plays a schizophrenic in 15 Park Avenue.

Konkona Sen Sharma plays a schizophrenic in 15 Park Avenue.

THE WAY FORWARD

Popular stars and personalities coming out with stories and personal experiences dealing with poor mental health, like Deepika Padukone speaking about her fight with depression or Anushka Sharma suffering from anxiety, help to draw attention to these issues. And filmmakers can also take a leaf out of the book of our stand-up comedians, who have begun incorporating relevant discussions into their acts like Sex and Sexability 2.0, which focused on Bollywood’s representation of mental health, disability rights and mental illnesses. Some hugely popular comedians, like Tanmay Bhat and Mallika Dua, also regularly spread mental health awareness through social media.

Actress Deepika Padukone speaks openly about her fight with depression.

Actress Deepika Padukone speaks openly about her fight with depression.

Anushka Sharma speaking out about her struggles with anxiety helped draw attention to the issue.

Anushka Sharma speaking out about her struggles with anxiety helped draw attention to the issue.

Spreading the word Some hugely popular comedians, like Tanmay Bhat and Mallika Dua, regularly spread mental health awareness through social media.

Spreading the word Some hugely popular comedians, like Tanmay Bhat and Mallika Dua, regularly spread mental health awareness through social media.

Mallika Dua

Mallika Dua

Note to the media: Mainstream media in India also needs a corrective, away from a sensationalised or even romanticised portrayal of mental illness. Suicide is almost always sensationalised; the Indian media does not follow a set of guidelines… potentially causing great harm. The content produced and a subtle change in attitudes in the past few years show that mental health (and illness) may finally receive the regard it deserves, yet there is a long way to go. When a country’s media and movie industry has leverage over the mindsets of its general public, it becomes its inherent responsibility to use it to its advantage and bring vital discussions to light.

Shruti Venkatesh is an aspiring Clinical Psychologist and Research Assistant at De Sousa Foundation, currently in her fourth year as a student of Psychology. She has been trained in REBT, TA, Forensic Psychology and Clinical Psychotherapy, and volunteers at NIOS and SPJ Sadhana.

This piece was first published on The Health Collective