50 Years After Emergency, Faultlines Still Remain Open In India

Fifty years on, the Emergency is less a concluded epoch than an unsettled question.

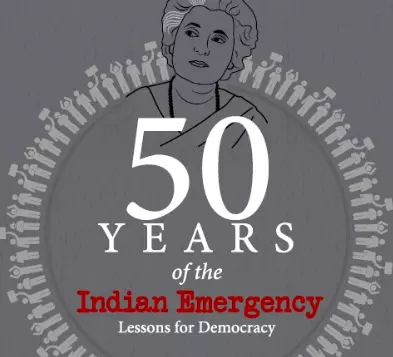

Hyderabad:It’s easy to think of the Emergency as history’s severest warning about the fragility of Indian democracy. At the Hyderabad launch of “50 Years of the Indian Emergency: Lessons for Democracy” at Vidyaranya High School on Wednesday, what emerged instead was a layered conversation about how that moment still breathes through constitutional practices, police institutions, regional experiences, and narrative memory.

The event felt more like a public excavation of certain democratic fault lines that India still has not closed. As editor Peter Ronald deSouza reminded the audience, “the daughter of Nehru won over the mother of Sanjay when she revoked the Emergency.”

The evening began with deSouza, former director of Indian Institute of Advanced Studies (IIAS), setting out the dilemmas of writing a book on a subject so often revisited. He explained how he and Harsh Sethi, former consulting editor of Seminar, chose to commission contributions across law, economics, literature, and politics, so that no single narrative would dominate.

He requested to ask not only why Indira Gandhi imposed the Emergency but also why she eventually withdrew. To him, the subjectivity of the decision-maker remains critical to understanding that historical moment. “Decisions are important, and the subjectivity of the most important decision-maker has disappeared from our social science literature,” he added.

Sociologist and legal scholar Kalpana Kannabiran, brought a more personal note.

She said her essay examined “the resistance politics of law” in Andhra Pradesh, where state violence during the Emergency took on a particularly raw form. She spoke of a “decoupling” between administration and policing with civil servants pushed through welfare programmes, including the Bonded Labour Abolition Act, while police torture and extrajudicial killings created a climate of fear. This paradox, she suggested, has left a playbook for later governments.

Rather than continue along institutional lines, Sasheej Hegde, philosopher, pulled the discussion into theory and memory. Calling himself an “Emergency child,” he said the period gave him “an extra edge of consciousness.” To him, the book supplies the pieces to “make sense of the event,” but scholarship must also “make present the event.”

The economic picture that followed provided a stark counterpoint. Economist Errol D’Souza asked the audience to look at trade-offs. He pointed to neglected data from the 1970s like per capita national income growth at 1.1 percent between 1971 and 1975, and inflation peaking at 17.8 per cent in 1974. He also drew attention to the more intimate essays in the book, like letters exchanged between Madhu and Pramila Dandavate, where “our sweetest thoughts are in our darkest times.”

Fifty years on, the Emergency is less a concluded epoch than an unsettled question. The book, the conversation in Hyderabad, and the memory it awakens remind us that democracy is never merely constitutional order. According to the panel, it is always about decisions made under duress, the institutions that survive or deform, and how we tell their stories.