360 degree: Zero dark visibility - The cloud over our cities

India’s capital New Delhi is one of the most polluted cities in the world. Smog persists well into January — a health risk for millions. The highest court in the land stepped in to issue a directive that shut over a thousand schools and kept people off the streets. What’s alarming however is how cities across the rest of India mirror Delhi’s several green blunders. What Delhi needs to do immediately, as should Allahabad, Patna, Raipur and Gwalior – is to set up green buffers, ban the burning of crop stubble and garbage, decongest traffic, set up dust traps at construction sites and vacuum clean the roads…

When the Supreme Court on November 10, 2016, directed the Central Pollution Control Board to come back within 10 days, with strategies to strengthen air quality monitoring in Delhi and the National Capital Region, along with a plan for a graded response to the severity of air pollution, it was the first time that any authority had taken cognisance of Delhi’s recurring and annual smogs this year. At the onset of this year’s winter, the choking haze of pollution was the worst in living history! Our meteorologists and scientists had predicted that the wind would be at a standstill and pollution would spike to severe levels on Diwali day. That’s exactly what happened. But before the Diwali smog had a chance to thin out, meteorological scientists told us that a lower-level anti-cyclone — a weather phenomenon that prevents the dispersion of smog — had developed around Delhi on November 2. There was virtually no wind. The smog thickened and worsened, and according to the Indian Meteorological Department, is the worst smog and with the poorest visibility in over 17 years.

To add to Delhi’s woes, Diwali was followed by farm fires intensifying in Punjab and Haryana, the proverbial icing on the pollution mud pie, which continued for over a week until November 7 until the winds did the cleaning. By then, pollution levels had spiked to 7-8 times the normal. By November 5, 2016, the levels were 14 times the standard. This surpassed the Great London smog of 1952, that had killed thousands within a week. There is enough evidence in Delhi and other parts of the world to prove how emergency hospital admissions related to cardiac and respiratory symptoms increase manifold when pollution spikes. Some governments have smog alerts and take emergency remedial action to protect the vulnerable — children, the ailing and the elderly. The health advisory linked to the Indian Air Quality Index states that when the smog reaches a severe level putting the vulnerable at risk, a proactive warning is issued to encourage people to stay indoors and avoid exposure. Particularly, in a city like Delhi, where every third child has impaired lungs...

Little question therefore that the onus, to inform people about the potential risks they face and put emergency measures in place to stop pollution peaking, has to be on the government. Globally, emergency action kicks in the moment pollution hits the worst air quality level and persists at least for three consecutive days. Cities such as Beijing, Paris, London and several across the United States have such systems in place. Beijing shuts down schools, industrial units, halves the number of vehicles on the road with odd and even schemes, intensifies public transport and bans fireworks. Depending on the stringency, these measures help slow pollution peaking when the weather turns hostile and helps lower pollution. Responding to the public outcry, the Arvind Kejriwal Government announced a slew of temporary emergency measures as pollution persisted. The Delhi government shut schools, closed coal-based power plant in Badarpur, halted construction activities for 10 days, vacuum cleaned PWD roads, banned leaf burning and slapped fines on responsible officials.

The glaring omissions are the vehicles that remain out of the ambit of the emergency scheme even though vehicles contribute hugely toxic emissions very close to where people are. Ultimately, however, the effectiveness of these emergency actions will depend on stringent enforcement as much as zero tolerance. Yet this year Delhi could have been better prepared. It had one year to put measures in place since last winter when the Supreme Court had clamped down to control toxic emissions from trucks and cars, pushed for penal action on waste burning and construction dust, and started more vigilant monitoring of farm fires. The Delhi government did halve car numbers with its odd and even scheme. But any hopes that there would be a second bending of the pollution curve in Delhi were belied when an enduring action plan for a lasting impact on air quality was not put in place. No measures, either short or medium term were set to reduce pollution from vehicles, power plant, industry, biomass based cook stoves, waste burning, construction and farm fires in a time bound manner to meet clean air targets. The national capital region does not even have its own air quality data set to drive action.

If Delhi cant breathe, neither can Mumbai, Kolkata, Ahmedabad

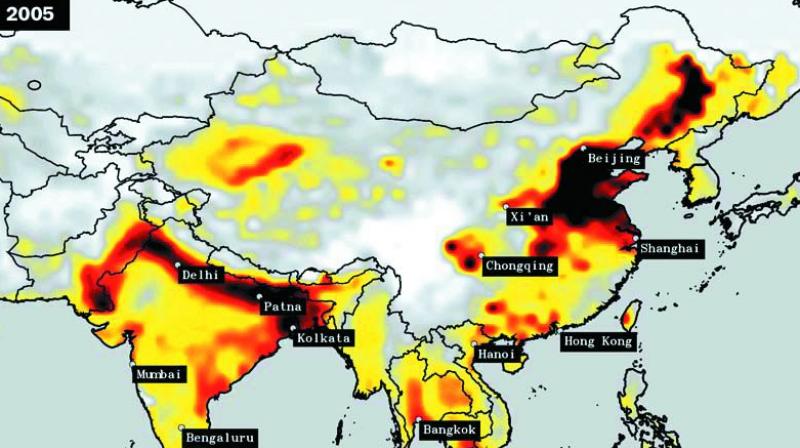

Delhi mirrors the crisis across the nation. Many of the smaller cities are more polluted than Delhi today, busting the myth that Delhi is a standout polluter. Half of India’s cities have particulate levels that are “critical”, putting sizeable sections of the urban population at highly toxic risk. Global Burden of Disease Estimates shows that air pollution is already the fifth largest killer in the country. This demands a national air quality planning strategy to enable and compel all habitats and cities to act to meet clean air targets.

The recent initiative of the Union Ministry of Health and Welfare to get health criteria in all policies and programmes across sectors, is a critical step forward. Air quality trends in several cities including Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Ahmedabad and others have shown pollution levels dropping after action is taken, saving premature deaths and illness. Surely, if it can be done in one, it can be done in all.

(Ms Roychoudhary is Executive Director of Research and Advocacy and head of the air pollution and clean transportation programme, campaigns for clean air and public health, Centre for Science and Environment.)