By invitation: Saving Bengaluru - Get masses to love public transport

The National Urban Transport Policy says 'streets for people' and only roads for vehicles.

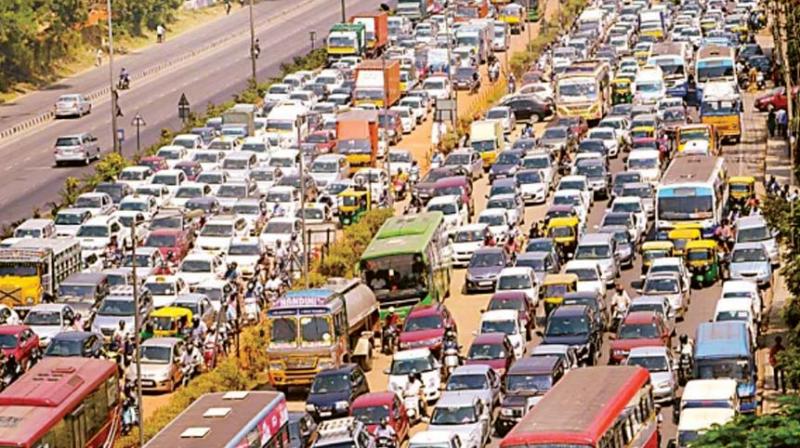

Commuting through Bengaluru is a harrowing experience, to say the least. In the absence of a reliable, integrated public transport system, citizens are left with no choice but to buy their own vehicles, which, understandably, contribute to the ever-worsening melee on the roads. The government's approach to city-planning is dictated by making room for these vehicles, which at best, may ease the situation temporarily but create problems for the future. The National Urban Transport Policy says 'streets for people' and only roads for vehicles.The steel flyover proposed in 2016, which would have drained the state exchequer apart from causing drastic harm to the city's green cover and its architectural aesthetic, was met with widespread resistance. Sustainable, carbon-conscious growth takes place through carefully planned expansion, integrated public transport, restricted or paid parking and pedestrian-friendly zones, all of which will encourage people to leave their cars at home and hop on a train or a bus instead

Few lessons have been learned from the debacle, however, for the government, undaunted by the mass furore, has proposed a second structure, this time from Shivananda Circle. But is creating more room for private vehicles really the answer? Urban transport planning in Bengaluru is distinguished by a singularly myopic approach, aimed more at filling political kitties than establishing a long-term, sustainable transit solution in a fast-expanding city. Over the last ten years, Bengaluru has emerged as a shining example of what not to do! Where do we go from here?

Layouts and land acquisition:

Progress and expansion are hamstrung by a few significant obstacles, some related to policy and others to a lack of political will. At the heart of urban expansion lies the availability of serviced land, which should be connected by a network of roads. The peripheries of the city are distended through grid or ring radial networks - Bengaluru uses the latter but could do so more effectively. In Bengaluru, the construction of ring roads seems to be guided by the availability of land and real estate interests, instead of the other way round. This should have been anticipated in the 1990s, but it wasn't, resulting in congestion caused by an over-reliance on a few roads. More than ever the city needs to develop more efficient road network and better delivery of serviced land for its peripheral demands of expansion.

There are some planned colonies in Bengaluru - Jayanagar, for instance - made recognisable through their street nomenclatures. Unfortunately, the planning model is very slow, for it involves the tedious process of acquiring land and then making planning layouts based on obsolete methods of reserving land for certain purposes based by strangling planning regulations on the buildings.

Acquiring agricultural land for peripheral urban development has always been tenuous: compensation is unevenly distributed, as farmers giving up their land invariably give in to their apprehensions and stall development plans. The only profit here is made by the developers. Town planning schemes (TPS) that use land pooling mechanisms have proved far more feasible; cities in Gujarat are good examples. Land is demarcated for a layout and people are asked to surrender around 40% of what they own. They are happy to do this, for the land is used by the government to develop amenities like roads, parks and a network of pipelinesinfrastructure. What you get in the end is a geometrically-shaped plot that abides a wide enough road.

Owners speculate on the value of their land to make a profit through Town Planning Schemes, which ensure this. Land that was sold in acres is now measured in yards. This way, landowners who would have had to negotiate, reluctantly, at agricultural rates, can now compete in the urban land market, with property backed by roads, pipelines infrastructureand a host of civic amenities. Speculating landowners can negotiate directly with developers, the government gets its roads and well-equipped community spaces and developers are kept happy too. In many cases, farmers invite the planning authority to develop their land.

Citizens pay a betterment tax to meet the expenses borne by the government for infrastructure development. Magically, this tax matches with the compensation amount for 40% of land that government acquired from the land owners. Nobody actually pays anybody money and what we're all left with is well-planned, holistic development. In this way, new layouts formed on the peripheries also get easy access to the city centre. Karnataka should adopt this method for its urban development needs.

Building an integrated transit system:

The second idea is about integrating and expanding the public transport. The establishment of a successful public transport system begins with access. How is the commuter going to access the metro or railway station? Does it involve a frantic hunt for parking space or a relatively stress-free ride in a bus or taxi? What incentive does the average commuter have to choose public transport over a private vehicle? Is anyone looking into the economics of commuter choices?

BMTC, the state-run bus service, is in commendable shape, with a fleet comprising some 6.000 buses. Its services and operations, however, haven't been upgraded in a while and few attempts have been made to integrate the bus network with the suburban rail or Namma Metro. Little coordination takes place between BMTC and BMRCL, which should be conceptualising a single-ticket mechanism that works across modes of transport. Otherwise buses and trains will operation in isolation and public transport will always struggle to survive. Families who live on the peripheries of the city are forced to buy then own vehicles, which adds to the congestion and locks us into a certain motorised lifestyle.

People will use public transport only if they have an incentive, or if its benefits outweigh those of driving a privately-owned vehicle. Pedestrian-friendly zones that provide access to Metro stations, an efficient bus service and paid-parking services are all enabling mechanisms in this process. TenderSURE is one of the few initiatives in keeping with transit-oriented development and could be used to enable pedestrian access to and from Metro Stations. Paid parking, with preference given to commuters using public transport will also encourage people to leave their cars behind.

A successful city requires transit zones that are easily accessible through public transport and pedestrian zones. In this IT heartland, technology-driven solutions are always at hand and we must embrace them - fast. Urban development must include the provision of serviced land, backed by an efficient road transport, along with investments in the integration and expansion of public transport. If not, we must resign ourselves to the chaos!

The writer is an architect and urban planner. He is currently Associate Professor, Centre for Environment Planning and Technology University, Ahmedabad (As told to Darshana Ramdev)