Would have been hard for Centre to justify continuance of Sec. 377'

It is only a physiological variation that occurs in a very small percentage of the population, says Arvind Datar.

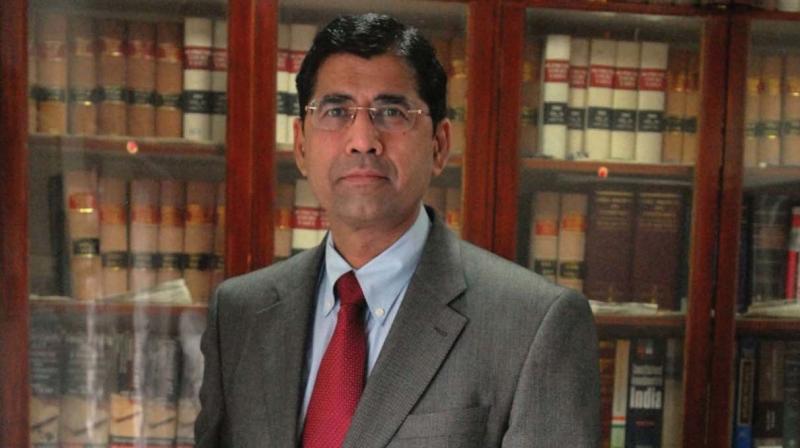

On September 6, the Supreme Court partially struck down IPC Section 377, which criminalises gay sex and homosexuality between two consenting adults. Senior advocate Arvind P. Datar, who was one of the lawyers who fought for the gay community, speaks with J. Venkatesan on the landmark verdict. Excerpts:

The Supreme Court has given a historic verdict in the LGBTQ issue. As a senior advocate you have spearheaded the fight for justice to the gay community. What is your take on the judgment, which has partly declared IPC Section 377 unconstitutional?

The writ petitions were filed to challenge only one part of Section 377, the portion that made even same-sex relationship among consenting adults a crime. The challenge was to the basis of Section 377, which was embodied in the phrase “carnal intercourse against the order of nature”. This was a law drafted in 1860 and medical evidence has now clearly established that a same-sex relationship is not against the order of nature. It is only a physiological variation that occurs in a very small percentage of the population. The referral order also indicated that the Constitution Bench would deal with this limited issue and, to that extent, the petitioners have succeeded.

On December 11, 2013, a two-judge Supreme Court bench of Justices G.S. Singhvi and S.J. Mukhopadhaya upheld Section 377 holding that it does not suffer from the vice of unconstitutionality. The court had then left it to Parliament to “consider the desirability and propriety of deleting Section 377 from the statute book or amend the same”. How did this sudden turn around happened?

The 2013 decision of a two-judge bench reversed the landmark ruling of the Delhi high court in 2009. The high court judgment had elaborately examined the entire history of the legislation and also noted the legislative progress in several counties. The earlier criminalisation of same-sex relationships was based on certain religious beliefs and a lack of understanding of why such relationships occur. The high court judgment was extremely well written. Unfortunately, the two-judge bench did not consider the reasoning of the high court but reversed the judgment on untenable grounds, particularly pointing out that the issue of decriminalisation should be left to Parliament. This was an incorrect approach as the statute, which becomes void with the passage of time, can be struck down by the Supreme Court or high courts. The Supreme Court has repeatedly pointed out that the Constitution is a “living document” and has to keep pace with the changing needs of each generation or the felt necessities of time. The Supreme Court did not bother to consider that a law made in 1860, based on no evidence but on prejudice and religious beliefs could not be sustained in a civilised democracy in the 21st century. The 2013 Supreme Court decision put the clock back to 1860.

Looking back, Section 377 should have been automatically rendered void by the recognition of the right to privacy, since sexuality is a private issue. What prompted you and others to file petitions for declaring this section unconstitutional? Do you think the court ought to have struck down the entire section without exception?

A statute cannot be automatically rendered void; it has to be expressly declared as unconstitutional by a competent court. The original petition was by Naz Foundation, an NGO. To avoid any objection on issues of locus-standi, the petitioners, who actually belong to the gay community, filed writ petitions under Article 32 because their individual fundamental rights were at stake. Each of them woke up every morning as a potential criminal, who could be arrested and sent to jail. That is why individual writ petitions were filed by the people who were actually affected by Section 377 continuing to be on the statute book.

It was not possible for the court to strike down the entire section, as the other parts of Section 377, dealing with children and animals, will continue to be valid. This was also made clear in the referral order.

It will raise a host of questions relating to parenting and adoption, housing, military service, employment and inheritance. Following decriminalisation, denial or restriction in such matters would invite legal action, since the right to equal access would be violated. Though the Supreme Court has declined to examine these while dealing with the present set of petitions, the judiciary will eventually have to ponder over them, even if Parliament legislates in the matter.

The issues relating to marriage and adoption are complex and will require extensive legislative amendments to the laws dealing with those subjects. For example, the Hindu Marriage Act and the Special Marriage Act both proceed on the basis that a marriage is between persons of the opposite sex. Various sections of these laws will have to be changed if rights of marriage and adoption are to be given to members of the gay community.

On the second day of hearings, additional solicitor-general Tushar Mehta filed an affidavit declaring that the government would leave the validity of the law entirely in the hands of the court. Do you think that this stand of the Centre has helped the Supreme Court in deciding the issue?

The stand taken by the Central government was laudable. It did not oppose the petitions for the sake of opposition. Perhaps, it realised that same-sex relationships have been decriminalised not only in Western democracies but even in Israel, Trinidad, Fiji and so on. It would have been very difficult for the Central government to justify the continuance of an archaic portion of Section 377 in the world’s largest democracy and which rightly prides itself on being governed by the rule of law.

Any other aspect of the judgment you would like to express? What impact this verdict will have on society as a whole?

The result of the judgment is that same-sex relationships will no longer be a crime and all persons of the LGBT community can live a life of dignity and free of fear or harassment. Further, such relationships cannot be a ground to disqualify a person either at the time of recruitment or at the time of promotion. Similarly, any other benefits that are given to citizens cannot be denied only on this ground. At the same time, the validation of these relationships will not mean that the right to marry automatically follows. Such further rights will have to await either amendment in the existing law or fresh legislation.

B09