After Doklam, more realism' by China's PLA?

A strong personality like Mr Modi in power in India is never to China's advantage.

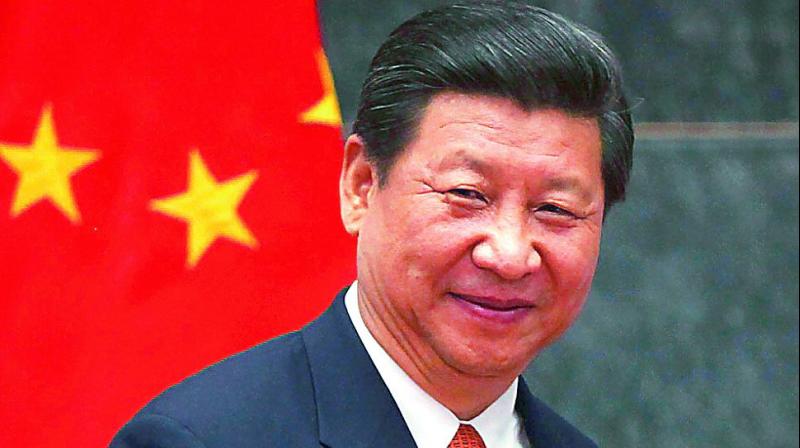

If one applies any sense of rationale the automatic conclusion would be that Doklam was a planned input or a seized opportunity as an influencing element for the 19th congress of the Communist Party of China — it was a Xi Jinping special, a contribution to China’s naked ambition under him to be viewed as a power which could address issues as it wished and coerce even large nations to submission. President Xi has personally achieved much in the last fortnight, with the elevation of his status and philosophy to that of his illustrious predecessors, Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. Through the last five years he worked passionately to achieve this and perceived that at the time of decision on his future status and position in history, he had to be seen as the sole facilitator of China’s progress to superpower glory. A part of the process to do the above was the projection of China’s international power. The activities which were designed to do this included the high-profile Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) conference in Beijing in May 2017. Preceding that for a period of time the South China Sea (SCS) issue, and China’s refusal to yield any space on its claims, occupied the narrative. This culminated in the refusal to abide by the decision of the international tribunal that gave credence to the US allegation of China being outside the rule-based international order.

As a natural competitor for strategic space in Asia, India was viewed as one emerging nation, a neighbour too, with which China had not achieved anything using coercive power anytime in recent past. This perception appeared to further cement after India’s refusal to be present at the BRI conference in Beijing. So an issue had to be created, and Doklam presented just that opportunity. Perhaps it occurred just incidentally and was grabbed as being suitable to ratchet up the strategic advantage. It did not go China’s way due to India’s steady, mature and non-coercive response. After 72 days, with attempts at crude psychological warfare through military demonstrations in the depth and one of the most ineffective and poorly-thought information campaigns employing state media; it turned to India’s advantage. There were few options for President Xi but to draw down. A conflict situation on the border could not have reached any finality before the big event — the 19th congress. Despite all calculations there wasn’t a single guarantee that China would be in a position of military advantage any time without opting to enlarge the conflict; that in the international environment of today would not have given China any strategic advantage either.

A careful analysis of the reports and statements in Global Times and People’s Daily belied any notion that China, 27 years after adopting “war under informationised conditions” as a basic doctrine, had achieved anything substantial in the PLA’s non-contact strategy. Such blatancy, lack of subtlety and utterly misplaced arrogance more often works to the advantage of the adversary. Victory and defeat are terms that can’t be explained through such standoffs. Mr Xi achieved much at the 19th congress in coming to be the undisputed leader of China for the next five years. In fact, with no identified potential successors, Mr Xi rules the roost with prospects of a third term. His philosophy, titled “Thoughts on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era”, is now enshrined in the constitution; it supplements and in fact overrides the Maoist and Deng philosophies.

How will this translate into effect in terms of Mr Xi’s attitude towards India, now that he has achieved what he wished to at the 19th congress and the future lies open? He would be wary of the sudden changes taking place in US foreign policy with engagement by important US functionaries in different nations prior to President Donald Trump’s coming visit to Asia, particularly China. It is likely that Mr Xi will await further US moves and assess the emerging quad alliance — US, India, Australia and Japan — and the seriousness with which it may create alternatives to the One-Belt-One-Road (OBOR), bridge the oceans and access other continents. The addressing of India after Mr Xi’s anointment can go many ways. First, an abrasive followup to the attitude adopted during and just after Doklam. This could be an ego-based response to seek opportunities in the near future to overcome the embarrassment at Doklam. Much depends on how deep is the perception of China’s embarrassment in the PLA’s and Mr Xi’s own thinking. It needn’t be restricted to overt border-based military activity or walk-in operations to claim lines, forcing more standoffs. It would appear extremely immature, though given the Chinese response in the state media, this is the kind of action which will restore so-called “pride” in China’s perceived self-superiority. However, it would have learnt its lessons in handling border standoffs too. The year 2018 could be considered an important one by China in terms of Sino-Indian relations, in which China may invest much with intent to politically embarrass Prime Minister Narendra Modi in order to weaken him before the 2019 general election. A strong personality like Mr Modi in power in India is never to China’s advantage.

The feasibility of China wishing to push for a major Indian military embarrassment remains an option. Wary of the fact that India’s strategic confidence is increasing and with greater military modernisation this will only increase further, China could well be tempted to trigger a situation in which escalation remains in its control. It is likely to re-examine the dynamics of its collusive cooperation with Pakistan and determine how winnable such a situation will be. A top-of-the-head assessment lends itself to the deduction that given India’s recent advances and redeployment at its northern borders, its capability to hold its own in the event of a border war is high. That is what the Army and Air Chiefs keep harping on when confronted about dual threats. It is general war that will remain a questionmark; the unbridled use of missiles and rocketry in depth against strategic objectives, a field in which India has advanced, but the asymmetry remains. The political objectives which China may seek are yet unlikely to be delivered through such actions as escalation to the oceans would still remain in India’s hands. Prudent minds in the PLA would have war-gamed this to the last. Wars are not just fought out of frustration, their terminal state is more important than the romance of the trigger. Under these circumstances, after Doklam in particular, a greater degree of realism may have entered the PLA’s war room considerations. None of these should point towards anything immediate in terms of a Sino-Indian standoff.