Privately, he cried out to God

The world knows of saints, patriots and social revolutionaries.

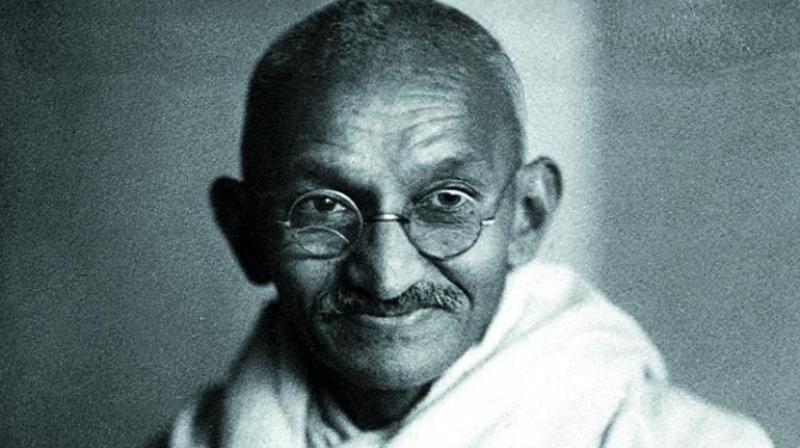

Mahatma Gandhi has seven surviving grandchildren and numerous biographers. As one who belongs to both groups, let me share with readers of the Deccan Chronicle my thoughts, 71 years after his death, about Gandhi.

I was twelve-and-a-half when he was assassinated in Delhi, where I was going to school and where, between 1946 and 1948, Gandhi spent good portions of his final two years. His warmth towards my siblings and me (we saw him often though briefly) was expressed in laughter, hugs and thumps on the back. I loved him. But family first was not Gandhi’s motto. He gave most of his time to Hindu and Sikh refugees from Pakistan, to Delhi’s vulnerable Muslims, and to people like Nehru, Patel, Maulana Azad and Rajendra Prasad, members of free India’s first cabinet, who wanted Gandhi’s support as they faced the challenges of Partition.

Six decades later, in 2006, I completed my Gandhi biography. This was long after I had studied and portrayed the lives of two remarkable men who were also very close colleagues of Gandhi’s (Rajaji and Sardar Patel) and soon after writing the biography of another exceptional individual and close associate, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, who had spent 12 years in British prisons and 15 years in Pakistani prisons before his death in 1988.

In a previous study, Understanding the Muslim Mind, I had depicted the lives of Sayyid Ahmed Khan, Iqbal, Jinnah, Azad and four other Muslim figures from the sub-continent’s recent history. In addition, in 1999m I had published Revenge & Reconciliation, an overview of Indian history from the times of the Buddha and the Mahabharata to the end of the 20th century.

I give all this background so that readers may know that for me Gandhi is a figure from a broad history that I have tried to understand, not just a beloved grandfather.

The world knows of saints, patriots and social revolutionaries. I found the historical Gandhi to be all three, spiritual seeker, national leader and social transformer.

With every breath of his, Gandhi seemed to remember Rama, his favourite name for God. With every breath of his, so it also appeared, Gandhi fought to rebuild India’s spine, enabling compatriots to stand erect and look the Empire in the eye. Equally unceasingly, he asked fellow-Indians steeped in hierarchy to look at other Indians as equals.

I found that some of his British adversaries, Churchill included, saw only the anti-imperialist in him. Dismissing Gandhi’s involvement in moral, social and economic questions, Wavell (the general who was the Empire’s penultimate viceroy in India, immediately preceding Mountbatten) even wrote in 1946 that he felt anti-British ‘malevolence’ in Gandhi, and that Gandhi’s goal was ‘the establishment of a Hindu Raj’ (Viceroy’s Journal, 439, 314).

While Jinnah made the same charge, Hindu adversaries attacked Gandhi for rejecting Hindu Raj and seeking Hindu-Muslim reconciliation. The truth, I learnt, was that Gandhi wanted no one to coerce anyone. He wanted no one to submit to coercion. And he wanted everyone to respect every fellow human being as an equal.

In 1933, Gandhi’s close British friend, Charles Andrews (who was ‘Charlie’ to Gandhi and almost the only person to call Gandhi ‘Mohan’) pressed Gandhi to focus solely on the removal of untouchability ‘for the whole remainder of your life, without turning to the right or the left’. Recalling that Gandhi had ‘again and again’ said that with untouchability Indians were ‘not fit’ for swaraj, Andrews asked his friend not to try ‘to serve two masters’. The question of independence could be left to others, said Andrews (David M. Gracie, ed., Gandhi & Charlie, Cowley, Cambridge, Mass., 1989, p. 155).

This is how Gandhi replied:

My life is one indivisible whole. It is not built after the compartmental system —satyagraha, civil resistance, untouchability, Hindu-Muslim unity… are indivisible parts of a whole… You will find at one time in my life an emphasis on one thing, at another time on other. But that is just like a pianist, now emphasizing one note and now [an]other. But they are all related to one another (15 June 1933; Collected Works 55: 196).

The social, the moral and the political merged into a single impulse in Gandhi’s life. No wonder a Gandhi statue stands today next to the British Parliament, and people the world over connect Gandhi to the insight that humanity is one and to the recognition that hatred of fellow-humans is folly.

Historians examining his life have found it hard to separate Gandhi the general who won several victories for his nonviolent armies from the private, often isolated and praying Gandhi who cried out for strength and wisdom from God.

Sometimes the two Gandhis appear together. On August 7, 1942, in Mumbai, when Gandhi was going to launch his last movement for liberation, Quit India, his secretary Mahadev Desai told another close associate, Kaka Kalelkar: ‘This evening’s is the most important meeting of [Gandhi’s] life. He has decided to pray before setting forth.’

No one knew how the Empire or the Indian people would respond to the Quit India call. The prayer-song loved by Gandhi, Narsi Mehta’s Vaishnava Jana was sung, as Gandhi and eight or so others prayed. Kalelkar thought that Gandhi’s face during the singing ‘shone with the pure radiance of trust in God, a firm resolve and gentleness’ (Kalelkar, Gandhi Charitra Kirtan, Nava-jivan, 1970, p. 42.).

Imprisonment soon came for Gandhi and scores of thousands, including for Kasturba and Desai, who both died in detention at Gandhi’s side. Across India, hundreds fell to British bullets. In 1947, however, the British quit India.

As Hindu-Muslim violence besmirched the dawn — in Delhi and elsewhere in India and Pakistan — Gandhi fought for sanity. Part of his response was a daily meeting with a small group of Delhi’s Muslim leaders. On October 26, 1947, which was Eid day, Gandhi told this group:

Jesus Christ prayed to God from the Cross to forgive those who had crucified him. It is my constant prayer to God that He may give me the strength to intercede even for my assassin. And it should be your prayer too that your faithful servant may be given that strength to forgive (CW 89: 411).

Some indeed wanted Gandhi killed. Armed with hidden revolvers and explosives and a plan to kill him, seven men arrived on 20 January at his prayer-meeting at the Birla House garden. An explosive was set off at one end of the garden, but the rest of the plan miscarried.

Sulochana Devi, a poor woman, bravely shouted at the man who set off the explosive, who was apprehended by others and handed to the police. The other would-be killers slipped away in a waiting taxi. The next day, Gandhi spoke about the attack on him:

You should not have any kind of hate against the person who was responsible for this. He had taken it for granted that I am an enemy of Hinduism. Is it not said in Chapter Four of the Gita that whenever the wicked become too powerful and harm dharma God sends someone to destroy them? The man who exploded the bomb obviously thinks that he has been sent by God to destroy me.

But… if we do not like a man, does it mean that he is wicked?... If then someone kills me, taking me for a wicked man, will he not have to answer before God?... When he says he was doing the bidding of God he is only making God an accomplice in a wicked deed…

Those who are behind him or whose tool he is, should know that this sort of thing will not save Hinduism. If Hinduism has to be saved it will be saved through such work as I am doing. I have been imbibing Hindu dharma right from my childhood. My nurse, who literally brought me up, taught me to invoke Rama whenever I had any fears…

Do you want to annihilate Hindu dharma by killing a devout Hindu like me? Some Sikhs came to me and asked me if I suspected that a Sikh was implicated in the deed. I know he was not a Sikh. But what even if he was? What does it matter if he was a Hindu or a Muslim? May God bless him with good sense (CW 90: 472-73).

Six days later, on 27 January, Vincent Sheean, an American reporter, met Gandhi. On Sheean’s request Gandhi translated for him the Ishopanishad verse recited in his evening prayers: ‘Renounce the world and receive it back as God’s gift. And then covet not.’

Gandhi explained, Sheean would write, that the last four words were important, for a renouncer was often tempted to covet again. Sheean felt that Gandhi’s words reached out ‘from the depths to the depths’. (Vincent Sheean, Lead Kindly Light, Random House, New York, 1949, pp. 190-93.)

It would seem that this man who was ready to face, forgive, and pray for his assassin was also polishing his soul for an expected meeting with his Maker.

Three days later, when Gandhi was killed on 30 January, my ten-year-old brother Ramchandra and I, two years older, were taking part in a running event in school. Taken to Birla House, we saw his body lying on a white sheet on the floor. Our father Devadas, Gandhi’s youngest son, was sitting beside it, along with Mountbatten, Nehru, Patel and others. There were flowers near the body and prayers were being sung.

It seemed a peaceful scene. Foolishly I imagined that my beloved grandfather would stand up and start walking. He didn’t, but 71 years later his thoughts continue to travel.

‘Hate not,’ he said. ‘Fear not,’ he added. ‘Know the other person’s pain,’ he sang. Gandhi was not perfect; no human being is. But his message rings true. The world seems to need it.