Citizenship rows threat to India’s cohesiveness

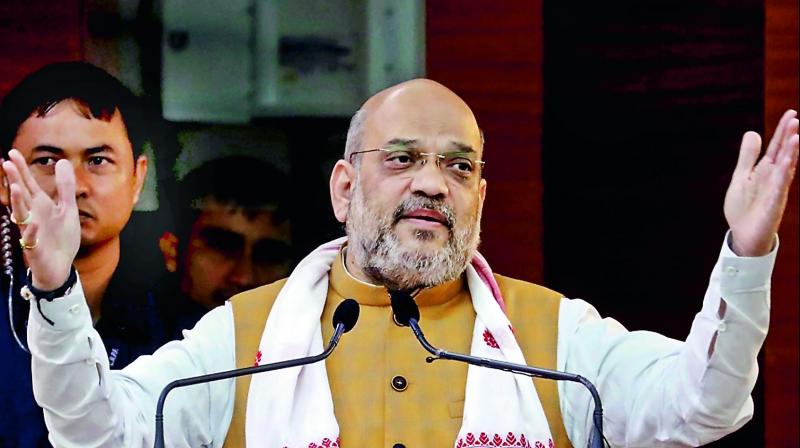

The assurances in the address of Union home minister Amit Shah to the North Eastern Council last weekend don’t seem to have ended the sense of disquiet among the people of the various states of the Northeast, and this was amply reflected in the observations by some chief ministers, notably that of Meghalaya’s Conrad Sangma.

In short, the Centre appears to be carrying less conviction than before. This is worrying for a border area. To the heady mix of sensitive issues that characterise the Northeast has been added the abrogation of the special status for Jammu and Kashmir under Article 370 of the Constitution.

This has suddenly raised a question mark over the status of Article 371, which applies to Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram. Article 371 prevents people from outside from buying land in the area (as in J&K before abrogation). Since 2015, the Centre has been attempting a final peace settlement with the Nagas. It has remained pending on several details, such as a separate flag and constitution for the Naga areas. After the Centre ended Kashmir’s special status, the Nagas are casting doubts on the sincerity of the negotiations.

Mr Shah sought to assuage them, saying that while Article 370 was a “temporary” provision, Article 371 is a “special provision”. This narrative is imaginary. In two rulings — of 1968 and 2016 — the Supreme Court has established there was nothing “temporary” about Article 370. The Nagas are unlikely to be impressed with the play of words. The wider recent problems of the Northeast burst forth with two near-simultaneous developments. The first was the government’s insistence on a pursuing a ham-handed course to roll out the National Register of Citizens, which seems to be aimed at arrivals from former East Bengal/East Pakistan and Bangladesh (the history of Assam’s immigration problem, which later came to be identified with “illegal immigration”, goes back a century). The other is the Citizenship Amendment Bill, under which the idea is to accept as “refugees” all non-Muslim immigrants (even so-called illegal ones) from neighbouring countries, but treat the Muslims — most of whom are dirt poor — as “infiltrators” and “termites”.

This idea of granting citizenship on the basis of religion is repugnant to the principle of democracy. Even so, if many in Assam seemed not unhappy that one section of immigrants was sought to be identified (and deported or sent to detention camps), they are deeply aggrieved that another set of Bengali-speaking immigrants (of Hindu faith, typically) might be settled in Assam, and this is beginning to have a political fallout.

Regardless of how this impacts the BJP’s fortunes as a political party, the conundrum thrown up in Northeastern India, premised on the communal factor, has every potential to undermine the cohesiveness of the country in a sensitive border region. The Kashmir parallel in respect of Nagaland is causing further complications.