Tweaking needed on Highway liquor ban

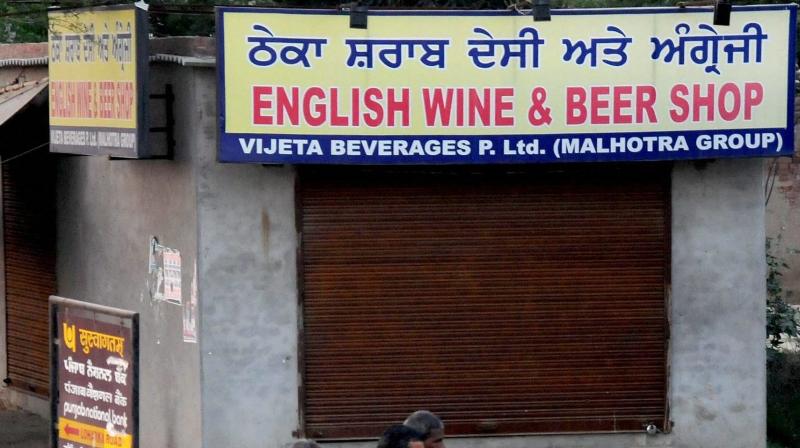

The Supreme Court ruling extending its ban on bars along national and state highways have led to several unexpected consequences: bars shut in all major cities on arterial roads classified as highways, but which really are highways only outside city limits. Hotels, restaurants, clubs and standalone bars that pay huge sums for liquor licences have been badly hit. The arguments relate to safe driving, which is why the court also insisted that all display boards of liquor vends and bars be banned. This has nothing to do with the larger principle of whether the sale of liquor should be permitted. The regulations that apply selectively to location near highways puts paid to the principal aim of preventing drinking and driving, that leads to a world record number of deaths on Indian roads in proportion to the vehicle population. Sikkim and Megalaya are totally exempt from the 500-metre or 220-metre rule as almost 90 per cent of liquor shops would have to shut to comply with this restriction.

Drunken driving is a global phenomenon that is tackled by governments and cities with strict police action leading to temporary driving bans and total withdrawal of diving licences for repeat offenders based on penalty points and fines. In India, however, the drive against drunken driving is used more to collect bribes, with the police in some states justifying it on the grounds that they pay politicians and bureaucrats to get plum postings and hence must recover their “investment” this way. This is callous in a nation on whose roads about 400 deaths occur in what can best be described as “daily massacre”, even if deaths due to drunken driving form only a part of those deadly statistics. There is no arguing against the social principle of curbing driving under the influence of liquor even if we are incapable of training drivers and road users on even the basic principles of road safety.

The excise collection from liquor, which undergoes high “sin” taxes, helps prop up state revenues, which in Tamil Nadu’s case, where liquor sale is a state monopoly, is as much as Rs 26,000 crores annually, and offsets the high cost of freebies and other state-run social programmes. The ruling doesn’t make a distinction between cities and the hinterland, through which highways run for several thousand more kilometres than inside towns, cities and metros. One way states can beat the ban is to name such highways as mere roads when they are within city limits even though that would mean trying to beat down the principle of road safety the court action was intended to serve. The Supreme Court itself might take a different view when it assesses the enormity of the problem its order may have created.