Shikha Mukerjee | Polls Won’t Lead To Orderly Power Shift in Bangladesh

Awami League ban, rising Islamist influence and street power cloud the February 12 election

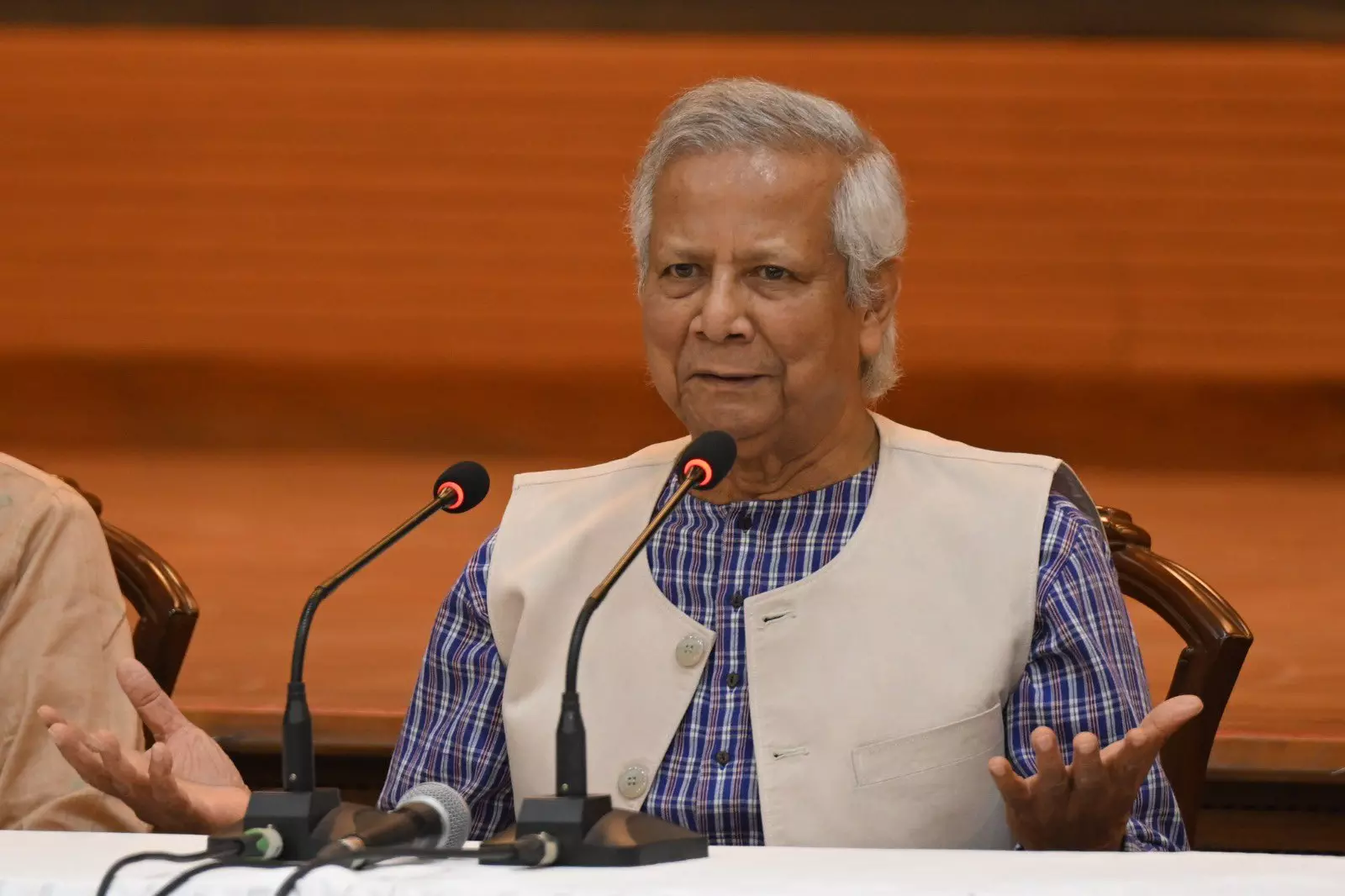

If the run-up to the election in Bangladesh scheduled for February 12 is as turbulent as it has been in recent weeks, peaking with the killing of Inquilab Manch leader Omar Sharif Hadi and the murderous attack on Motaleb Shikdar, arson and attacks on newspaper offices, spiralling tension and all-around fear, the sanctity of the election is not guaranteed. In his role as chief adviser, Muhammad Yunus has reiterated his pledge to provide peace, fairness and freedom to Bangladeshis as they exercise their franchise.

Since the promise is only partial, as the administration headed by Mr Yunus has banned the Awami League and declared it cannot participate in the election, trouble is inevitable. It does not require the warning or threat delivered by Sajeeb Wajed Joy, exiled son of his exiled mother, Sheikh Hasina, that Awami League supporters will hit the streets during the election to register their protest at being excluded. The burst of violence and its continuation, reflected in killings of two Hindus by mobs on the rampage, are signals enough that the Yunus administration is not in control of either the law-and-order situation or the political conditions nurturing the violence in Bangladesh.

The key player in the February election will be the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, now led by just-returned Tarique Rahman. With the Awami League’s exclusion, the BNP is the only broad-based party in Bangladesh, though it is neither secular, nor Islamist, nor liberal nor particularly committed to democratic governance or a corruption-free administration. The BNP is best defined by what it is not, rather than what it is. It has partnered up with the Jamaat-i-Islami as part of the Four Party Alliance and was one of the 18 parties, later 20 parties, that fought against the Awami League in elections that were not particularly free or fair.

The 2026 election will be different from all past elections, rigged or only partially manipulated. The difference will not be the degree of freedom that voters can exercise; it will be the choice that voters make. Bangladesh politics has never been as polarised as it is now, with the power parties like the Jamaat-i-Islami, which wants to bring in Sharia law and was blacklisted and banned by Sheikh Hasina for its alleged association with the Pakistan Army in 1971. In the fray will be Hifazat, an ultra-extremist Islamist party and the newly-formed National Citizen Party with a core leadership drawn from the 2024 uprising led by the Students Again Discrimination.

What is particularly significant is that the principal parties in the fray were all born after 1971, starting with the BNP. Regardless of their ideological position, all the parties are fundamentally anti-Awami League. Therefore, an election without the Awami League looming over the political space means that newer equations will emerge the closer it gets to election day. The Jamaat has already begun negotiations with other, obviously like-minded parties: “We want to see a stable nation for at least five years. If the parties come together, we’ll run the government together”, Jamaat’s Ameer (president) Shafiqur Rahman said in an interview at his office in a Dhaka area days after the party created a buzz by securing a tie-up with NCP.

The furore within the NCP over the arrangement is a pointer that the quest for stability necessary to fulfil the pledges in the famous July Charter for better governance and broader democracy could be jeopardised by instability.

Opinion polls in Bangladesh predict that the BNP will emerge as the largest party, with the Jamaat a strong second. While the Jamaat and BNP have been partners before, the two are not buddies any longer. As the anointed heir of his mother Begum Khaleda Zia, who passed away recently, Tarique Rahman has stepped into the leadership position but his leadership remains to be confirmed by the satraps who manned the party during its years in the wilderness, when it was harassed and penalised by the Sheikh Hasina regime. The party will ride a sympathy wave that will benefit Tarique Rahman, but he has to know how to handle it, burdened as he is with a reputation for corruption, abuse of power and a propensity to run when the chips are down, such as his exile in the United Kingdom for 17 years.

With a youth population, that is persons between 18 years and 35 years, comprising an estimated 33 per cent of the 16.5 crore people in Bangladesh, students and the left behind will be a critical factor.

Having successfully exerted power, albeit through hitting the streets and challenging the authority of the Sheikh Hasina regime in violent protests, Gen Z is unlikely to be docile if the results of the election do not fit in with their expectations of how governance and democracy function in Bangladesh.

In the 55 years since its birth, regime change has not been turmoil-free. The chances of the February election outcome being turmoil-free are not certain. The BNP, if it wins, will have to negotiate with the self-appointed custodians of good government in Bangladesh. If it falls short of a majority, it will need to find partners. While Tarique Rahman has made noises of approval about the NCP and attended the funeral of youth leader Hadi as soon as he returned to Dhaka, it is not certain that he can actually do business with them, just as it’s unclear if he can do business with BNP’s former ally, the Jamaat. How far Tarique Rahman is prepared to go in making concessions to the radical Islamist forces that have grown and are power hungry is an open question.

While India has made it clear that it will work with whatever regime is voted to power in free and fair elections, it has also made it clear that it wants a free, fair and inclusive election, meaning the participation of Awami League in elections and government formation. There is speculation that the BNP has struck a deal with the Awami League to lift the ban on it, anticipating that it will come to power after February 12. Whether it can do so, is an open question.

Just as vague is how the new government structures its relationship with India, which is seriously strained now, over among other things, giving Sheikh Hasina shelter and enabling her to address the people in Bangladesh through selected interactions with the media. Indian investments in Bangladesh have not been jeopardised through the turbulence. However, India is part of Bangladesh’s domestic politics, mirroring how Bangladeshi infiltration and violence against Hindus is an emotional issue in India’s domestic politics.

Shikha Mukerjee is a senior journalist