Sanjeev Ahluwalia | GST 2.0: A Major Reform or Sops for Hard-Pressed?

GST 2.0 must optimise across the three primary objectives: of reducing the incidence of tax on consumers; increasing its economic efficiency by reducing the number of rates; and generating more revenue via boosted consumption and growth.

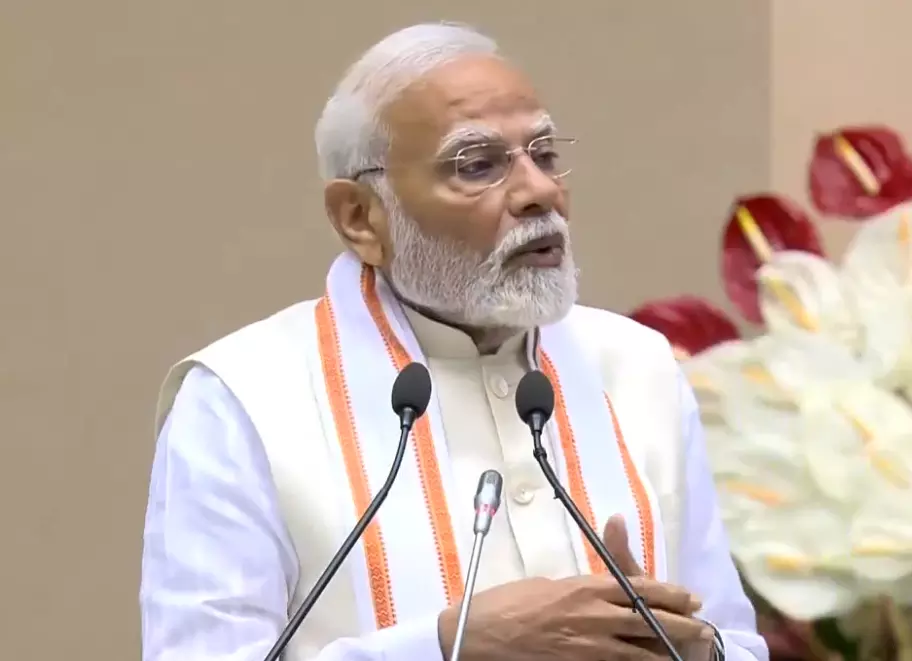

Prime Minister Narendra Modi promised structural reforms of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime in his Independence Day address which would lower prices, increase consumption, and thereby boost GDP. This long-term reform strategy is made even more urgent by the American intransigence in imposing penal import tariffs on India. The GST Council, chaired by finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman, has met this week to determine a new structure for GST 2.0 to replace GST 1.0 -- a value added tax implemented in fiscal 2017-18 which consolidated multiple indirect taxes levied by the Union and state governments into a single tax applicable across the country.

The benefits thus far have been significant. The value-added format avoids the “cascading effect” of tax levied on the tax already paid, by making all tax on input purchase deductible from the final tax burden, by linking the purchase invoice with the sale invoice. This also creates an incentive to avoid cash payments without a bill, thereby enlarging the tax base and revenue.

There is, however, much to rectify. First, the existing GST has six rates -- zero for agricultural unprocessed, unpackaged goods and social services, five per cent for high volume and low margin essentials and daily needs, 12 per cent for garments, processed food and telecom services, 18 per cent for electronic and electrical consumer durables, IT and business services and capital goods and 28 per cent for “sin” and luxury goods. including automobiles, tobacco products and coal. Plus, there is a special low rate of 1-3 per cent for gold, silver, cut diamonds and jewellery.

This multiplicity of tax rates encourages misclassification to evade tax and costs more administratively. Collection efficiency -- the share of tax collected versus the potential -- at about 60 per cent -- reflects a common problem of economies with multiple rates in Europe, where collection efficiencies are similar. In Brazil, a developing economy like India, the efficiency is below 40 per cent. In comparison, in New Zealand and South Africa, both with a single tax rate of 15 per cent, the collection efficiency is higher, at about 77 per cent and 98 per cent respectively. However, tax efficiency also depends on the composition of the tax base, which varies across countries, making a fair “apples to apples” comparison difficult. The UK, with three tax rates, has a collection efficiency of 70 per cent, far higher than in Europe, illustrating that institutional differences also matter.

In India. tax collection efficiency can be significantly enhanced by bringing alcohol and petroleum fuels under GST 2.0. These account for about five per cent of India’s GDP. The addition of these goods can boost the tax base by 12 per cent from Rs 140 trillion to Rs 157 trillion and the revenue collected by 60 per cent from Rs 25 trillion to Rs 40 trillion. Sadly, the political economy is not supportive. These provide about 40 per cent of the “own revenues” of state governments and are key to their fiscal sovereignty.

Only a grand bargain, giving more voting power to states within the GST Council, and safeguards guaranteeing tax buoyancy, would be necessary, but perhaps not as generous as the 14 per cent promised in GST 1.0, given low inflation prospects in future. States should also consider that fast expanding electrification of transport can severely damage future revenues from petroleum fuels. Bringing agriculture under GST can become possible only once it evolves into a commercially-oriented and profitable sector.

GST 2.0 must optimise across the three primary objectives: of reducing the incidence of tax on consumers; increasing its economic efficiency by reducing the number of rates; and generating more revenue via boosted consumption and growth.

An SBI research report suggests collapsing the existing six into five rates by ending the existing rate of 12 per cent and shifting products in the associated tax base (five per cent of total tax base) to the lower tax slab of five per cent. Similarly, the highest tax rate of 28 per cent (share in tax base of 15 per cent) could be ended. Two-thirds of the tax base moved to the lower tax rate of 18 per cent and the remaining five per cent share in tax base, moved to a new much higher tax rate of 40 per cent.

The net result is that for 80 per cent of consumers, the tax burden will remain the same. For 15 per cent of purchases, the tax burden will reduce by 7-10 per cent.

Just five per cent of purchases in the luxury, automobiles and “sin goods” segment will attract a hefty 12 per cent additional tax. This restructuring fits well with the objective of benefiting the largest set of consumers or holding them unharmed, whilst soaking the rich and the wayward via a higher “sin tax”, which partially pays for the tax reductions enjoyed by the middle class. Those at low-income levels remain unharmed.

This is clever accounting, but far from structural reform. The objective of improving the efficiency of tax collection significantly remains compromised to manage the near time impact on consumers and protect government revenue. The inflation impact is assessed at an additional 0.25 percentage points. SBI anticipates an overall deficit initially of unto Rs 1.1 trillion in the annual revenue collection, but expects this can be neutralised by the consumption boosting “income effect” of lower tax for consumers in 15 per cent of the tax base. Industry, however, is wary of demand compression in automobiles if they are included in the “sin tax” 40 per cent segment.

The weighted average rate of GST continues decreasing from 14.4 per cent at inception to 11.6 per cent in 2019 to 9.5 per cent in GST 2.0, illustrating the favourable direction of change in tax for a significant segment of consumers. Tax buoyancy will depend on how propensity to save windfall gains during tough times plays out versus the marginal propensity of

consumers to spend (mostly in the higher income-tax brackets). The tax structure remains complex with five rates, including a special rate for diamonds, jewellery and precious metals. Increase in the efficiency of tax collection will depend on the level of tax breaks given for products where demand is suppressed by income. There is also the issue of neutralising the likely differential impact across states depending on their income and consumption profiles. A good first step for meaningful engagement, in the spirit of cooperative federalism, would be for the finance minister to pledge that no state will be harmed by the change.

Whether some will be benefited more than others would then be her discretion.