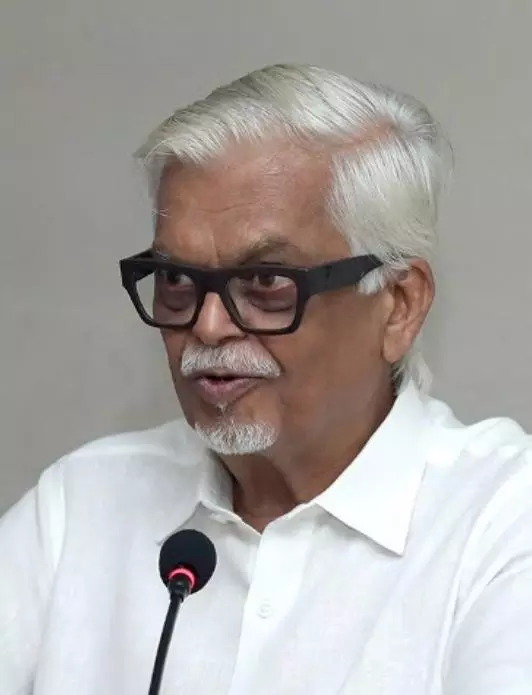

SANJAYOVACHA | Cartels, Customers, Cronies In The Captive India Market | Sanjaya Baru

A product of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s “leftist” phase, the MRTPC was set up in 1969 in response to studies that showed the growing power of monopolies, oligopolies and cartelisation in the Indian economy

This column is a tribute to my friend and columnist, the late Bibek Debroy. Bibek was chairman of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council when he passed away last November. A quarter century ago he was a columnist in a newspaper of which I was the editor. On one occasion when I was off on a vacation with my family, I requested Bibek to take charge of the newspaper’s daily editorial.

Bibek was at the time actively researching the damage that out-dated laws, rules, regulations and institutions were inflicting on the economy. He wrote an editorial questioning the functioning and relevance of one such institution -- the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Commission (MRTPC). A product of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s “leftist” phase, the MRTPC was set up in 1969 in response to studies that showed the growing power of monopolies, oligopolies and cartelisation in the Indian economy.

After the industrial policy liberalisation of 1991, the government’s commitment to battling these tendencies had weakened to enable Indian companies to scale up and become more globally competitive. By the turn of the century, the MRTPC had gone soft and was no longer very active in going after monopolistic and restrictive trade practices. Why not wind it up, asked Bibek. He did not stop with that question.

He went on to ask why the government should be spending so much money on a virtually defunct institution headed by a retired judge for whom, he alleged, the office was just a sinecure. The said judge promptly issued a suo moto notice of contempt of court, for the MRTPC had a legal status. Summon the editor, said the judge.

When I returned from vacation, I was informed that as editor I was required to appear in court and either defend Bibek’s editorial comment and face the consequences or extend an abject apology. The judge was a tough-minded gent who not only demanded an apology, that the newspaper’s lawyers advised I extend, but also imposed a fine. Within a year after this incident the MRTPC was wound up.

In 2002 the MRTPC was replaced by the Competition Commission of India. The CCI began on a hopeful note and was active for a while, especially after 2004 when the government of the day was serious about promoting a competitive business environment.

However, over the years even the CCI has lost its bite. Under-staffed and often ignored, the CCI has been unable to prevent the rapid growth of monopolistic and oligopolistic practices and the spread of cartelisation.

The merger of Air India and Vistara was a fit case for the CCI. It reduced the number of private airlines, and when the IndiGo crisis erupted it was noticed that while IndiGo had cornered 60 per cent of the civil aviation market, the merged entity of Air India and Vistara had 35 per cent of the market and the two airlines were carving up the domestic market, adopting restrictive trade practices. The IndiGo crisis opened the can of worms of cartelisation and cronyism in the civil aviation sector. It also raised questions about regulatory oversight, political interference, cronyism and gross mismanagement on the part of IndiGo.

Across several product markets, it has since been reported in the media, duopolies have come to exist. If IndiGo and Air India dominate the civil aviation market, we have Jio and Airtel dominating telecom, Asian Paints and Berger in paints, Tata and JSW in steel, Reliance, Adani, Tata and NTPC in power, UltraTech and Adani in cement, Google and Meta in online ads, Apollo, MRF and JK in tyres, and so on. Two, three or at most four firms dominate most goods and services markets.

Even when there are a few more firms as in private health care, with three to five corporate hospitals dominating a given geographical space, there is price fixing and cartelisation. The fact is that post-1991 economic liberalisation has allowed firms to grow but has also contributed to the dominance of a few in each product or services space.

In the past decade we have witnessed something more insidious -- first, the use of government agencies by big corporates to increase the latter’s market power; second, the emergence of oligopolies in the media that enables corporates to curtail media scrutiny. There is rarely any serious scrutiny of the operation of cartels, price fixing, market sharing and so on in different markets across the country in the national and business media.

In the face of oligopolistic practices, the CCI has been a toothless tiger, like the MRTPC in its final days. What is worse, today the government is being accused of enabling cartelisation. Consider the case of civil aviation. The board of the Tata Sons was reportedly not in favour of buying Air India when the Union government put it up for sale. The Narendra Modi government was keen on establishing its credentials as a

business-friendly government and was keen on privatising Air India. However, no corporate was willing to step forward and buy Air India. It was at this moment that the late Ratan Tata stepped in and persuaded the Tata Sons board to take over Air India. Board insiders say that Ratan Tata made an emotional appeal reminding the members that it would be a homecoming for Air India. The government had taken over Air India from J.R.D. Tata and it was only fair that the airline be returned to the Tatas.

When Air India was privatised the CCI should have examined the move and stepped in to prevent the emergence of an oligopoly. The CCI could have tried to prevent the merger with Vistara. If two separate boards running two separate firms, even if under the same Tata umbrella, some element of competition would have still been preserved.

The merger of Vistara with Air India and the ease with which a politically well-connected IndiGo was allowed to expand services created the duopoly that an embattled government is now trying to discipline. Rather than promote competitive markets, government policy in recent years has been to facilitate cartelisation.

Where is the CCI? What is it doing? Is it merely just another sinecure for retired officials? That was Bibek’s question about MRTPC a quarter century ago. To be fair, the record shows that CCI has been active and has been hearing and disposing off scores of cases. Yet, we find cartelisation on the increase. Is it the case that the CCI is going after the small fish while turning a blind eye to big fish?

Sanjaya Baru is a writer and economist. His most recent book is Secession of the Successful: The Flight Out of New India