Sanjaya Baru | The Many Hyderabads That We Now Live in

Once divided by the Musi, now united by diversity — Hyderabad’s story of many cities in one.

In 1947 the rulers of Hyderabad State did not want to be a part of the new Republic of India. Today, Hyderabad has become a mini-India and a metaphor for our national motto — unity in diversity. Perhaps due to its cosmopolitan character and composite culture, a mix of north and south, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru had famously called it India’s “second capital”.

Hyderabad, or what is now Greater Hyderabad, is many cities in one. Until not very long it was popularly referred to as the “twin cities” — Hyderabad and Secunderabad. When in fact it ought to have been referred to as “triplet cities” — “Old” Hyderabad, a “New” Hyderabad and Secunderabad. The city began as an urban settlement south of the river Musi. It then grew northwards, crossing the river. Then emerged Secunde-rabad. There is now a newer Hyderabad, the other side of the Banjara Hills, referred to as Cyberabad.

This metropolitan sprawl is now a “quadruplet” city comprising four socially and culturally distinct entities. Each of these four urban spaces has its own history, its own social composition and cultural characteristics. This could be said of some other Indian cities that have grown beyond their original geography, like Old Delhi and New Delhi, but the evolution of Hyderabad’s four-sided personality has been more organic than most other such cities.

Hyderabad was first populated south of the River Musi. It then expanded north of the river. In 1578 Ibrahim Qutb Shah, of Golconda’s Qutb Shahi dynasty, built Purana Pul connecting the southern and northern banks of the Musi and facilitating the northward expansion of the city. However, the seat of power moved north of the river only in the early 20th century when the young ruler, Mir Osman Ali Khan, chose to reside at the King Kothi Palace, rather than at the Old City’s Chowmohalla Palace, the residence of his predecessor.

By moving to King Kothi, the 20th-century Nizam implicitly promoted the northward expansion of the city even as it was increasingly populated by Telugu, Marathi and Kannada speaking subjects of his multi-lingual kingdom. Localities like Kacheguda, Tilak Nagar, Himayat-nagar, Narayanaguda, Chikkadpalli, Bashir Bagh, Nampally and Khairatabad became new residential localities and most of the 20th-century construction of new public buildings as well as palaces of higher and lesser nobility were in this space. The ruling elite moved into the adjoining hills, building large mansions in and near Banjara Hills.

The difference in the social and cultural life of these localities in the Old City and Hyderabad north of Musi has been brought out in a sharp and interesting manner in a series of essays written originally in Telugu, by Paravasthu Lokeshwar, and recently translated and published into English titled Sheher Nama: The Romance of Hyderabad’s Bastis (South Side Books, Hyderabad, 2025). Though the author does not in fact spell it out, what the essays show is that the Old City had a very different social and cultural rhythm compared to the neighbourhoods that came up largely during the course of the 20th century. Even as this part of Hyderabad was growing, a parallel development occurred further north thanks to the British, who maintained a cantonment in Secunderabad. Many early residents of Secunderabad came from the British territory of the Madras Presidency, and so Secunderabad became home to Tamils, Malayalis, Andhras, Parsis and Anglo-Indians.

Even during my school and college years, in the 1960s and early 1970s, I could feel the distinctive cultural and social difference between Hyderabad and Secunderabad. Incidentally, Secunderabad was where all the Hollywood and English movies would be screened at theatres with names like Plaza, Dreamland and Tivoli. For a long time, the only movie theatre playing English movies in Hyderabad was situated close to the Hussainsagar Lake, that separates the so-called “twin cities”, Embassy cinema. Most Hindustani movies would play at theatres in Hyderabad with names like Zamarud Mahal and Dilshad Cinema.

Hyderabad north of Musi has been the space in which much of the city’s politics and social life played out through most of the 20th century. The Nizam functioned from this space and so did the government of united Andhra Pradesh. This space was the political centre, even if not the economic centre. The latter moved increasingly to the north-west.

Secunderabad had its own appeal with its markets, restaurants, open spaces and movie theatres, but it was always the lesser of the twins.

Lokeshwar’s essays focus mostly on the localities of the old city and a few in what I call “new” Hyderabad. For tourists, Hyderabad was always defined by Charminar and Chowmohalla Palace. However, as Dinesh Sharma’s fine book, Beyond Biryani: The Making of a Globalised Hyderabad (2024) notes, there is more to Hyderabad than its distant and quaint history. Hyderabad has been a centre of research and teaching and Cyberabad is an extension of this personality of the city.

Over the past quarter century, ever since the city began growing beyond the Banjara Hills and crossed over into Jubilee Hills, Gacchi Bowli, Madhapur and so on, a fourth urban space, Cyberabad, has developed which is far more multi-ethnic in its composition with information technology, fintech and global capability centres recruiting young Indians from all over the country.

Today, as one drives from one part of Hyderabad into another, the difference is palpable. The lingua franca of the Old City remains “Dakhni” — a mix of Urdu, Telugu and Marathi, the language of social interaction that I grew up with. In new Hyderabad and Secunderabad Telugu, increasingly with a Telangana accent, is more widely spoken today than even a couple of decades back. Cyberabad has yet to develop a character of its own. At present, it is an agglomeration of concrete, steel, glass, boulevards, green spaces and gated communities.

Every time I return to my home city, I realise how many new inhabitants have made it their home and how even more socially and culturally diverse this metropolis has become.

Talented Indians from every corner of the country are flocking into this dynamic city. What is, however, worrying is the growing assertion of the newly rich and of religious extremists among both Hindus and Muslims. Hyderabad was known for its multi-cultural, multi-lingual and multi-religious character. The city’s new elites need to work hard at preserving this identity.

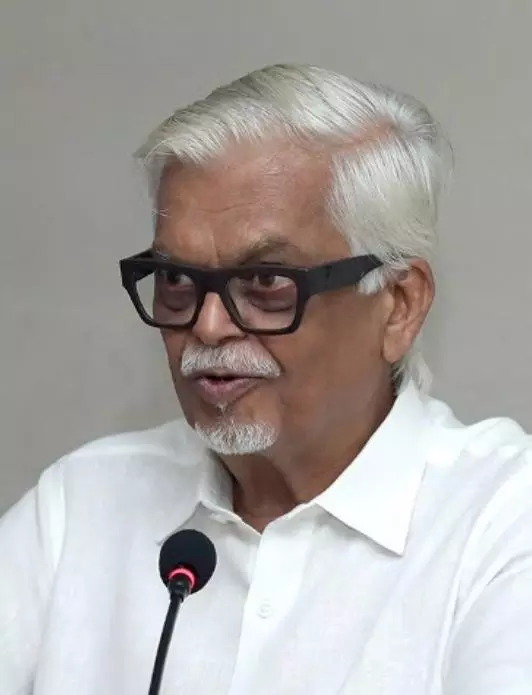

Sanjaya Baru is a writer and an economist. His most recent book is Secession of the Successful: The Flight Out of New India