K.C. Singh | In Trump Era, India Has To Recalibrate Strategy

India’s Independence Day this year had two important events overshadowing it

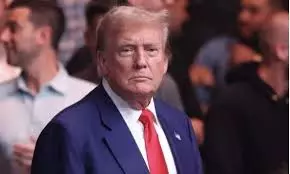

India’s Independence Day this year had two important events overshadowing it. One, Operation Sindoor in May, from which Pakistan emerged diplomatically stronger, with US support. The other, the much-awaited summit meeting in Alaska, later the same day, between US President Donald Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin. The summit was important for New Delhi because of US-imposed 25 per cent punitive tariffs on India for buying Russian oil.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s address from the Red Fort reflected both these concerns. He began by lauding the military operation and targeting Pakistan and its sponsored terrorism. Pakistan’s nuclear blackmail, he argued, would not deter India from punishing any future terrorist acts against India. Regarding the threatened punitive US sanctions, he announced protection for Indian farmers. This signalled to the United States India’s unwillingness to concede, in the trade negotiations, the US demand for India opening the agriculture and dairy sectors.

The Putin-Trump summit in Alaska opened with a red-carpet reception and a fly-past by US military aircraft. President Trump applauded, as his Russian guest approached. Then the two rode together in the US presidential limousine like long-lost friends. However, after the meeting, they only made statements, refusing to take questions. Also, the planned lunch was called off as both leaders returned home.

President Trump claimed that though no deal was made or any Ukraine ceasefire achieved, there was some progress. He said: “Ukraine has to agree to it. Maybe they will say no”. This implies that he failed to extract any concession from President Putin, hoping Ukraine buckles.

President Putin gained by transitioning from being a diplomatic pariah, with the International Criminal Court’s arrest warrant against him pending, to being warmly welcomed in America with flypasts and salutes. Mr Putin, as expected, successfully played Mr Trump, as he had in their six previous summits, during the first Trump administration. He defended Mr Trump’s old denials of any Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. He also endorsed Mr Trump’s claim that the Ukraine war in 2022 would not have occurred had Mr Trump been the US President. In both cases Mr Putin loses little while endorsing Mr Trump’s fact-free theories and massaging his ego.

This holds a crucial lesson for India. The Washington Post analysed recently the India-US tariff-induced tension. One factor singled out was Mr Trump’s repeated claims of mediating the India-Pakistan ceasefire. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s discomfort with those statements, leading to dodges and denials, has apparently bruised Mr Trump’s ego. Pakistan, on the other hand, promptly accepted the US role and even supported a Nobel Peace Prize for Mr Trump. This earned Pakistan presidential goodwill, versus US pinpricks on India.

After the Alaska summit, when interviewed by Sean Hannity of Fox News, President Trump said punitive tariffs on China for buying Russian oil are deferred because “the meeting went very well”. But, he added, he could review it in two or three weeks. About India he thought Russian oil imports stood cut, quipping: “Well, he (Putin) lost an oil client… which is India”. However, news reports indicate that India’s public sector oil companies are still importing Russian oil, unfettered by the government. President Trump, distracted currently, may revisit this issue if the Ukraine-Russia deal collapses.

Prime Minister Modi also announced in his Red Fort address that India was developing a comprehensive missile system for defence and attack. He christened it “Sudarshan Chakra”, after Lord Krishna’s lethal flying disc. This raises the question why now, and not post-Balakot in 2019? It was a strategic mistake to assume that abrogation of Article 370 and robbing Jammu and Kashmir’s statehood would solve the Kashmir issue and deter Pakistan permanently. The Pahalgam attack, followed by the effective use of Chinese planes and missiles to down Indian Air Force planes, as indeed the repeatedly aggressive posturing by Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff Asim Munir, confirm Pakistan’s continuing defiance.

China would now assiduously rectify gaps in Pakistan’s missile defence system, which allowed India to hit Pakistan’s military facilities and assets.

Former US President Ronald Reagan had initiated a move away from the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction, or MAD, by his Strategic Defence Initiative (SDI) in 1983. It involved a satellite-based, laser-using and computer-assisted command and control system. This rattled the Soviet Union, which lacked the resources to match what was labelled as “Star Wars”. Although not implemented during the Reagan presidency it had twin impacts. One, it unleashed research that led to subsequent anti-missile systems. It also led to the Communist control in the Soviet Union loosening, with Mikhail Gorbachev introducing “perestroika”, or economic reform. The Russian regression to an authoritarian order, blatantly breaching Ukrainian sovereignty, demonstrates that new weapons systems do not solve diplomatic and geostrategic issues. Thus, whatever India creates will get matched by Pakistan with Chinese help.

Deterring Pakistan has got complicated because the basic assumptions shaping Indian diplomacy in this century have collapsed. For instance, the concept is now questionable that growing India-US relations were untouchable because India was critical to balancing China’s rise. President Trump’s “America First” transaction-minded approach ignores such strategic thinking. Hence, China and India are seen as equally guilty of buying Russian oil, the former allowed even a longer rope.

The other assumption was that the US and its troops having left Afghanistan, during the Joe Biden presidency, Pakistan was of marginal interest to them. Mr Trump has been wooed successfully by Pakistan with exaggerated accounts of its oil, gas and rare minerals reserves. Pakistan is also seen as a nuclear weapons-possessing Sunni power, balancing Shia Iran.

Indian diplomacy thus confronts these new variables. The Modi government is handicapped by excessive dependence on former bureaucrats handpicked for Cabinet appointments or ambassadorial assignments in important nations. For example, to tackle President Trump, the Indian ambassador in Washington requires golfing skills, partying craft, networking with Mr Trump’s family and outreach to billionaires. Similarly, India’s external affairs minister needs the social skills, political access and charisma of Vajpayee-era personalities like Jaswant Singh.

Additionally, the national security adviser needs to think strategically and act dynamically. America’s former NSA Condoleezza Rice in her memoir explains that her job involved handling a trijunction of diplomacy, defence and intelligence. In India, former diplomats Brajesh Mishra and J.N. Dixit had the requisite skill-set.

In the contemporary global environment in the Trump era, the Indian government needs to recalibrate strategy, with unity at home and Machiavellian prowess abroad.