Civil-military ties: A major challenge for Imran's govt

The PTI-led government faces many challenges. One it does not acknowledge is that of civil-military relations.

The PTI-led government faces many challenges. One it does not acknowledge is that of civil-military relations. Yet, in a constitutional democracy, if civil-military relations are not clearly conducted within the framework of civilian supremacy they will, sooner or later, become problematic. Many see the current state of civil-military relations as providing a civilian mask for selective military rule. The political salience of the military in Pakistan is too obvious to be denied.

However, it is equally undeniable that civilian rule in Pakistan has largely failed to provide effective and acceptable governance. The reasons for this are many and generally known. They include the patriarchal nature of party politics; massive entitlement-based leadership and political corruption; extractive administrative and political institutions; endemic poverty and deprivation; and the “majboori” of the masses.

Moreover, the necessarily security-oriented nature of the state in its initial years enabled or compelled the military in Pakistan to play a political role beyond its normal remit. Over time, this came to be regarded, especially within the military, as the political norm.

The recently elected government will now have to overcome the weight of the past. Being “on one page” with non-elected subordinate institutions may have tactical advantages. But it cannot remain a policy imperative. If it does, it will undermine democracy, good governance, human resource development and, above all, nation-building. Accordingly, it is incumbent on both the civilian and military leadership to facilitate the proper development of civil-military relations within the context of civilian supremacy. After all, civilians comprise 99 per cent of the country’s population.

There is a view that for any elected government to successfully contextualise civil-military relations within the framework of civilian supremacy — a fundamental premise of the Constitution — it must first “stoop to conquer” the reservations of the military. These reservations relate not only to institutional interests; they also reflect an entrenched inclination of the military to regard its political salience as indispensable for the security and survival of the country.

This is also a response to the largely valid perception of civilian political incompetence and irresponsibility. Correcting this perception is, of course, easier said than done. There is the reality of the dismal record of civilian governance. Much of this incompetence is still on display. Parliamentary proceedings by and large provide a disgusting spectacle. Reportedly, over 300 parliamentarians including ministers have been suspended for not submitting details of their assets! There are also disparities in civilian and military power and differences in their institutional and political perspectives.

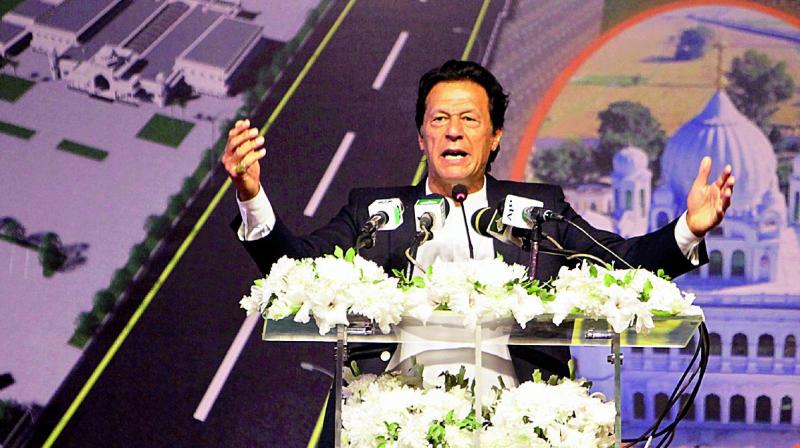

The Prime Minister seeks to transcend this political resignation and build a new political dispensation. As a result, the people are becoming more insistent in their demand for a just and responsive political order. Given the current empathy between the ruling party and the military there is a real opportunity to strengthen the democratic principle of civil-military relations under the rubric of civilian supremacy. This will entail progressively altering largely unarticulated but pervasive assumptions in the military that (a) it is an autonomous stakeholder in the governance of the country, (b) it should remain more or less exempt from supervision of elected civilian authority including Parliament, (c) its inputs in the formation of policies of particular interest to it should be taken as policy parameters, and (d) it should have protection from the criticisms of civil society and the media.

For any elected civilian government to alter these assumptions it will first need to establish the credibility of its governance as well as its moral and political authority. In the past, elected governments have, almost without exception, irrevocably lost their moral and political authority within a year or two of assuming office. This undermined their ability to face down the political assertiveness of unelected institutions. Military rule, for all its limitations and disadvantages, has often been superior to civilian parliamentary rule because of the latter’s record of bad governance and the betrayal of its pledges. Nevertheless, the longer-term costs of deviations and dilutions of democratic governance are massive, and are still being paid by Pakistan.

The Quaid departed far too early. Since his passing, no civilian government has delivered on its promises. Neither, for that matter, has military rule whether covert or overt. Accordingly, despite misgivings about the early performance of the PTI-led government, there is no reason to give up on it because of initial trials and errors. All the available alternatives to the PTI, civilian or otherwise, have been tested and found woefully wanting. After a year, however, the government will need to stand on its own record of delivery. The misdemeanours of its predecessors will no longer provide an explanatory or political crutch. Its success in this regard will also go a long way towards resolving the perennial problem of civil-military relations.

The writer is a former Pakistan high commissioner to India

By arrangement with Dawn