Pak in a fix over J&K, but India’s challenges remain

The Mumbai attacks of November 2008 marked the high point of these assaults.

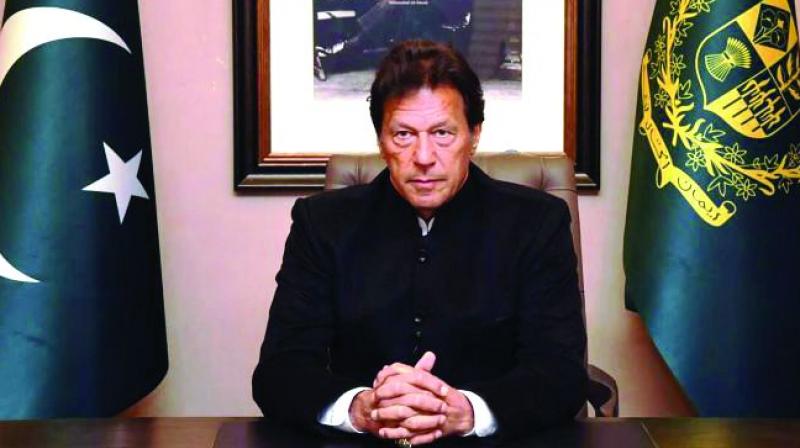

Pakistan’s leaders have responded to India’s Kashmir-related initiatives with shock and bewilderment. After the August 5 announcement in New Delhi, the Pakistan National Assembly went into a frenzy, with parliamentarians hurling abuse at Prime Minister Imran Khan. In exasperation, he asked his colleagues: “What do you want me to do? Attack India?” This frustration reflects a new scenario in South Asia.

For the past 30 years, the Pakistani armed forces have used the instrument of jihad as state policy in the Kashmir Valley by backing street demonstrations and, more lethally, organising cross-border incursions of trained and highly-motivated militants. A well-organised and substantially funded support system exists in Pakistan to provide religious indoctrination and training in weapons, bombings and organisation of cells to carry out acts of terror across India.

The Mumbai attacks of November 2008 marked the high point of these assaults. These attacks, with their careful planning, multiple targets and sheer ruthlessness, clearly affirmed their origins in Pakistan and convinced the international community that Pakistan was both the fountainhead and the sanctuary for state-sponsored extremist groups.

Pakistani writers have criticised the recent Indian initiatives as a “unilateral abrogation” of the Shimla Agreement of 1972 and the Lahore Declaration of 1999. But they fail to note that these agreements had committed the two countries to settle differences through “peaceful means”. Again, during the “back channel” discussions during the Pervez Musharraf presidency, India had insisted that Pakistan ensure “an end to hostilities, violence and terrorism”. At no stage has Pakistan ever rejected violence as its preferred instrument to settle matters to its advantage.

However, having kept India under pressure for at least three decades, Pakistan now finds itself in a difficulty. The “surgical strike” of September 2016 and the Balakot air attacks by India in February this year have made it clear that a terrorist attack from across the border will meet with firm retaliation and could escalate into a full-scale war. Pakistani commentators now fear that if there is now any violence in Kashmir, Pakistan will be blamed and there could be a sharp Indian response.

Hence, being reluctant to instigate violence at this stage of the delicate discussions with the Taliban in Doha, Pakistan has no option but to agitate its concerns before an international audience. However, Pakistan has little credibility due to its established affiliation with extremism. Again, the world’s major nations are distracted by other concerns — the Gulf crisis, Brexit, Ukraine, the Sino-US trade war, North Korea. This has meant that no country has come forward to give Pakistan the backing that it so desperately seeks.

Over the past two decades, the countries of West Asia have built solid political and economic ties with India, and they also see India as a valued partner in addressing their concerns relating to extremism, which are linked with Pakistan providing a congenial habitat for jihadi groups to flourish.

China’s first official statement on the Indian initiative referred only to its concerns relating to Ladakh; for the rest, it only called upon the two countries to “exercise restraint”. However, under Pakistani pressure, it finally agreed to back “closed door consultations” at the UN Security Council in New York on Friday, the first discussion on the Kashmir issue since 1965, though Pakistan did not get much satisfaction from this conclave.

Pakistan’s foreign minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi had prepared the ground for this by warning his countrymen not to live in a “fool’s paradise”, and made it clear that there would be no warm welcome for Pakistan at the UN. He also spoke of India being an attractive investment destination, including for the “guardians of the Ummah”!

Pakistan does have the capacity to win over even hostile US Presidents by reminding them at different times of its crucial role in addressing issues of importance to them. Recently, it has convinced President Donald Trump that its assistance is essential to conclude a deal with the Taliban that would enable American troops to go home. Hence, Pakistan sought to put pressure on Mr Trump by suggesting that it might have to shift its troops from the Afghan to the Indian border, thus jeopardising the peace process with the Taliban. Given Pakistan’s deep and abiding links with the Taliban, the US is hardly likely to be blackmailed in this crude manner.

While Pakistan’s diplomatic effort is unlikely to be fruitful, we in India need to remain wary of the human rights groups, including the UN high commissioner for human rights (UNHCHR), Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. For the past three decades, these organisations have castigated India for abuses in Kashmir.

In July this year, the UNHCHR issued a 43-page report in which India was criticised for: the use of excessive force against violent protests; the lack of justice for past abuses, and the immunity enjoyed by the security forces for serious human rights violations. India had officially dismissed the report; while the UNHCHR South Asia head responded that India was “unwilling to confront its own human rights failures”.

Clearly, the principal challenges for India lie at home. The abrogation of Article 370 and the end of the state’s special status has been an article of faith for the Sangh Parivar ever since 1950. However, beyond ideology, the success of the initiative will really lie in fulfilling the commitment of genuine integration of Kashmiris into the national mainstream and their all-round development, while respecting their unique identity and culture.

According to recent news reports, the Northern Army commander in 2001, Lt. Gen. Rustom Nanavatty, had prepared a “strategy for conflict resolution” for the state. He had called for a “long-term, coherent, comprehensive, all-encompassing strategy” to restore normality — defined as a situation where democratic institutions can function without hindrance.

The elements of this strategy had included fulfilling the legitimate aspirations of the people; synergising the functioning of the Central and state governments, and improving governance.

Hopefully, such a strategy has been shaped and is ready for implementation. Any failure on the domestic front will leave India in the crosshairs of human rights groups, which will do no good for our international standing or even self-image.

The writer is a retired diplomat who has served as India’s ambassador to several West Asian capitals