How China compromised its socialist ideals and cozied up to America in 1971

China was the first major power to make a move by openly warning India

Yahya's Kremlin setback was on account of his narrative being diametrically opposite to the reports that the Kremlin was receiving from its diplomats in Dacca and Islamabad... Significantly, after the emissary's departure, the Kremlin responded positively to Indira Gandhi's appeal for help for logistical support to deal with the worsening refugee crisis. It announced the dispatch of a fleet of transport aircraft with its crew and ground support staff and equipment to Calcutta to ferry the excess refugees… to the new… [camps] set up in Madhya Pradesh.

The end of April and early May was also when the Bangladesh issue had become a major pawn in the chessboard of international diplomacy. China was the first major power to make a move by openly warning India “not to meddle in Pakistan's domestic affairs. If it did so, it would 'burn its fingers”. China's open threat to India caught the attention of all Indians, especially the Leftists of West Bengal. What sounded very odd to us was that the Chinese made no mention of the mass killings that Pakistan had resorted to, setting off history's biggest ever exodus of refugees into India... Instead of empathising with India, Peking stepped up its arms supply to Pakistan and informed Pakistan’s Bengali envoy, Khwaja Mohammed Kaiser, that it had already issued a veiled threat to India that it would intervene if the situation warranted it.

Not to be outdone, on 3 April, Soviet President Nikolai Podgorny delivered an ultimatum to Yahya to “immediately stop the genocide”, making headlines in all Calcutta dailies. On 17 April, Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin followed this up with a message to Yahya urging him to peacefully negotiate a political settlement with the stakeholders. He had stressed that any settlement must take into account the “lawful wishes of the parties involved in the crisis. Also, the interests of populations of both East and West Pakistan should be factored into consideration for finding a solution” (as reported by Russian news agency TASS). [The diplomat] Gurginov informed us that Kremlin, of course, had serious doubts about Yahya’s ability to work out such a solution because it was aware of the mindset of the regime that Yahya represented and also of the ongoing genocide in East Pakistan.

Kremlin’s apprehension had been conveyed to Mrs Gandhi’s advisers by the then Soviet envoy in Delhi, Nikolay Pegov. The Soviet leadership suspected that the Chinese were in favour of prolonging instability in East Pakistan as that would help them to make significant political inroads into the region… The Soviet leadership concurred with the Indian assessment that prolonging the liberation war might help the armed Naxalite radicals infiltrate and take control of the liberation war by resorting to political subterfuge.

Declassified Indian archival records reveal that even the Soviet defence minister, Marshal Grechko, had told the then Indian envoy in Moscow, D.P. Dhar, many times that the threat to India’s security was not so much from Pakistan, which Delhi could handle on its own. It was graver from its “unpredictable and dubious northern” neighbour, China. Grechko had suggested to Dhar that “some kind of treaty of friendship and co-operation” between India and the Soviet Union, would be a good preventive measure against Chinese and Pakistani aggression against India. The same treaty proposal had been conveyed to Mrs Gandhi’s advisers by the Soviet envoy in Delhi, Nikolay Pegov. The then Indian foreign minister, Sardar Swaran Singh, was lukewarm to the idea…

This assessment of China’s possible involvement in the East Pakistan imbroglio impelled Mrs Gandhi’s policy planners to provide an all-out support to the Bangladesh liberation war effort. It pursued this objective with single-minded devotion though China was firing salvo after salvo in its polemical battle against the Soviets. Peking’s position was that “Soviet revisionist and social imperialist” forces were in cahoots with “arch Indian reactionaries, running dogs of the Kremlin” trying to invade and annex East Pakistan in their bid to set up a “puppet regime there, in so-called Bangladesh”. Peking's salvo was in response to Soviet President Nikolai Podgorny's statement of 3 April, calling upon Yahya to “immediately stop committing genocide in Bangladesh”.

Almost at the same time, Indira Gandhi demanded an end to Pakistan's mass killings in Bangladesh in a shriller tone both inside and outside Indian Parliament. Peking’s provocative reaction to Podgorny’s appeal and Indira Gandhi's speech were not unexpected…

The Chinese Communist Party leaders hoped that their anti Soviet and anti-India blast would please President Nixon. The American president was at that time trying to build bridges of understanding with them and, according to declassified White House papers, had a “total dislike” for Indira Gandhi, whom he considered to be a “Soviet stooge”. For her father, he had “nothing but scorn and an intense personal aversion”. Besides, as those documents reveal, he harboured racial prejudice against Indian women… The Chinese leadership felt that the best way to tune in to the American line and cozy up to White House was by launching a virulent anti-Soviet and anti-India tirade.

It is very pertinent to mention here that at a time when no Bangladeshi leader was daring to take on the Chinese leadership for their nefarious anti-Bangladesh role, it was Maulana Bhasani, leader of a pro-China faction of National Awami Party, who had the temerity to dispatch scathing telegrams to Mao and Zhou Enlai, openly questioning them about their socialist and communist credentials for not standing by the oppressed people of Bangladesh… About the same time, a much-respected and noted literary icon of Dacca, Shaukat Osman, who had sought shelter in Calcutta, in an open letter addressed to the Chinese Communist Party leaders posed almost identical questions that Bhasani had asked but with such great literary panache and finesse that local Calcutta dailies could not but help publish it. Bhasani had sent the telegram after he came to Calcutta in mid-April and had held discussions with Tajuddin [Ahmad] in this regard. But it evoked no reaction, not even an acknowledgement from the Chinese Communist Party.

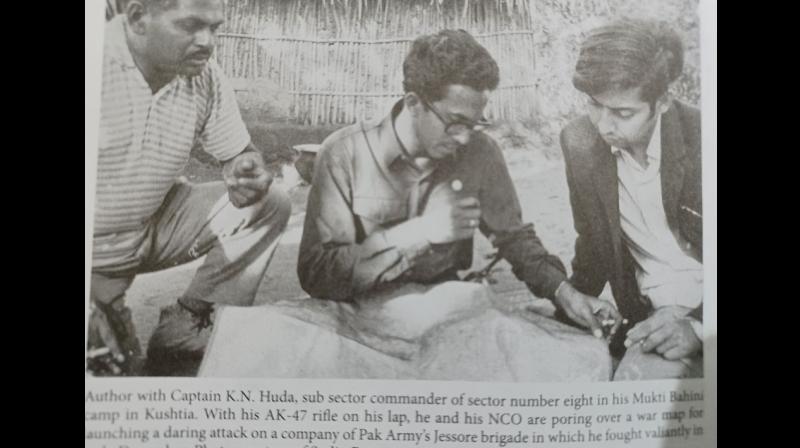

Excerpted from Bangladesh War: Report from Ground Zero (Niyogi Books, pp. 209) by Manash Ghosh. Ghosh had famously predicted the coming of the war in January 1971 as a cub reporter by writing an article in the Sunday Statesman. He was also among the few journalists who covered the war from the beginning to the very end on 17 December.