Satyagraha is Gandhi’s lasting contribution

In April, the government took lead in marking the centenary of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

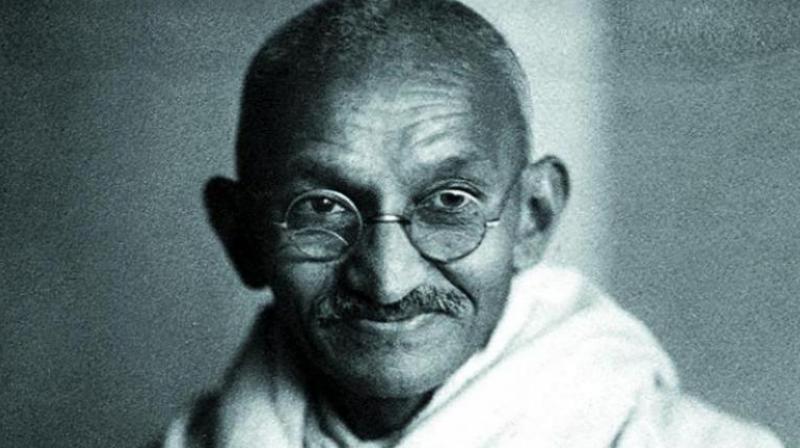

Despite a surfeit of recollections, essays and interpretations on Mahatma Gandhi to mark his 150th birth anniversary, the last word can never be said and there remains space for more. This is especially true as the real challenge to adhere to Gandhi and Gandhism begins now, after rituals have been observed, statements made and his political legacy sought to be co-opted. But, as we begin marking this landmark through the year, the moot point is if this year can be different.

Gandhi was not unidimensional. As a political leader and communicator par excellence, he was an astute practitioner of his craft; as negotiator and team-person, he bordered on being dogged and as a social and economic visionary, he certainly held archaic and often impractical ideas. Much before Indians get to understand the true political value of Gandhi, they are exposed to his “experiments” with truth and become the progenitor of a legacy that the youth wish to have to no part of. Much of Gandhi’s personal choices, his sexual abstinence contrasted by the constant companionship of young women, his culinary practices and his non-accommodative ways have for long been ridiculed.

Despite romanticising idyllic rural life, and it becoming a draw in recent years among the well-heeled in the autumn of their lives, migration from villages to urban settlements is the easiest way to personal progress and growth. In this backdrop, Gandhi’s village rootedness and assertions in the 1930s when he was quietly awaiting the appropriate opportunity to launch the “final” assault on British colonialism, stands out as odd. It is elements from this phase of Gandhi’s life, many of which surely retain value, that have been the emphasised by this government. The complete identification of Gandhi with the Swachchh Bharat campaign, essential and not one which can be doubted in its intent, may have done wonders for the campaign but has reduced the Mahatma to being a broom-wielding loin-cloth clad oddity that people will pay lip service to every now and then but whose philosophy they will miss out on.

In April, the government took lead in marking the centenary of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. The emphasis was either on issuing standard remembrances or on whether the British would issue a formal apology or not. Prime Minister Narendra Modi led the political leadership in paying tributes by saying that the “valour and sacrifices” of the martyrs “on that fateful day” can never be forgotten: “Their memory inspires us to work even harder to build an India they would be proud of,” he wrote on his Twitter handle. President Ram Nath Kovind termed the incident as a “horrific massacre, a stain on civilisation, (a) day of sacrifice (that) can never be forgotten by India”. Rahul Gandhi, who was still officially the Congress president, wrote on the visitors’ book: “The cost of freedom must never ever be forgotten. We salute the people of India who gave everything they had for it.”

None of the leaders mentioned above or others in their respective flanks recalled what led to the tragedy, after all it was not just a ritualistic Baisakhi Day congregation. General Reginald Dyer's panic reaction had a political backdrop - the first indication of the latent power of Gandhi’s Satyagraha, and the possibility of an anti-colonial struggle metamorphosing from being an annual or periodic jamboree into acquiring a mass character. It cannot be ignored that innocent people were gunned down because British officials feared the gathering nationwide campaign against the Rowlatt Act. There certainly was political purpose in people violating prohibitory orders in Punjab. People in large parts of the country were angered at restrictions on personal freedom being imposed by the draconian Rowlatt Act, formally called the Anarchical & Revolutionary Crimes Act, a war-time legislation which the British administration attempted to reintroduce with the objective of restraining nascent nationalistic sentiment.

Leaders paying tributes, especially those from the Opposition ranks, would have done better service to their political cause by recalling Gandhi’s role in giving courage to the people to stand up against the might of the British Empire. After all, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre must be recalled not just for the brutalities of the army but for the bravery of the people and the cause which they believed in. It has to kept in mind that the proposed law spawned one of the most memorable newspaper headlines, used by a Lahore daily, “No Vakil, No Daleel, No Appeal.” Mahatma Gandhi took the lead and successfully called for the first all-India upsurge against British colonialism at a time when such call to action was unheard of. It required the political vision of Gandhi to realise that politicisation of the people was not dependent on literacy levels and that the poor and powerless could be encouraged to stand up for their rights.

The Gandhian initiative against the Rowlatt legislation has particular value in contemporary India given the ease with which the government introduced amendments to the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act in the last Parliament session and the current political discourse, fanned with official patronage, which equates opposition to government with anti-nationalism. The call for Satyagraha, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and protests against it are not the only initiatives of Gandhi that require recollection. The centenary of each of these have to be clubbed together and celebrated with as much gusto as his 150th birth anniversary.

Events in 1919 also led Gandhi to include the Khilafat movement in the nationalistic agenda, merge it with the non-cooperation movement and lead the first mass protests against the British. It was Gandhi’s insistence on explaining to people that it is “the right recognised from time immemorial of the subject to refuse to assist a ruler who misrules” which gave courage to people. Gandhi also declared it was the duty of Hindus to “associate themselves with their Mohammedan brethren” on a religious matter. Indeed, in the 150th birth anniversary year, it is more important than ever to recall Gandhi’s messages on inter-faith harmony and the political rights of people.