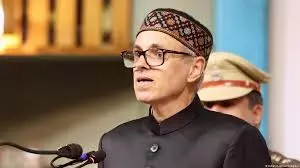

Kishtwar Zakat Regulation Not Arbitrary, Says J&K Chief Minister Omar Abdullah

Abdullah explained that community leaders had highlighted troubling instances where money was collected in the name of individuals whose identities or medical conditions could not be verified

SRINAGAR: Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister, Omar Abdullah, on Friday said that the administrative order issued by the Deputy Commissioner of eastern Kishtwar district to regulate the collection of Zakat and other charitable donations during the Islamic fasting month of Ramadan was neither arbitrary nor imposed without consultation.

What began as a local administrative measure—framed by officials as an attempt to ensure transparency and prevent the misuse of religious charity—quickly escalated into a contentious political and religious debate, drawing sharp reactions from across the spectrum.

But the Chief Minister Omar Abdullah, addressing the Assembly during the ongoing budget session in Jammu, clarified that the directive emerged from inputs provided by local Muslim leaders, religious committees, and community representatives.

According to him, the administration had convened meetings with district officials ahead of Ramadan, instructing them to coordinate with local stakeholders to ensure smooth preparations for the holy month. In Kishtwar, he said, religious leaders themselves raised concerns about the sudden proliferation of NGOs and individuals who appear only during Ramadan to collect donations—often in the name of patients or charitable causes—without any accountability regarding the use of funds.

Abdullah explained that community leaders had highlighted troubling instances where money was collected in the name of individuals whose identities or medical conditions could not be verified. In some cases, he noted, it was unclear whether the patient on whose behalf funds were raised was even alive. Such practices, he argued, not only mislead donors but also undermine the credibility of genuine NGOs working transparently throughout the year.

It was on the basis of these concerns, he said, that local religious bodies requested the Deputy Commissioner to introduce a regulatory mechanism to prevent fraud and protect the sanctity of charitable giving. “The DC did not issue the order on his own,” Abdullah emphasised, urging legislators not to politicise the matter. “We should not mix religion with politics. Some matters require dialogue and understanding at the local level rather than political confrontation,” he said

The controversy stems from a detailed order issued on February 18 by District Magistrate Pankaj Kumar Sharma under Section 163 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), 2023. The directive mandates that no individual, NGO, trust, society, or committee may collect Zakat, Sadaqah, or any form of charity—whether in cash, kind, or digital form—without valid registration and prior written clearance from designated authorities, including the Waqf Board Unit Kishtwar, the Imam of Jamia Masjid Kishtwar, the Majlis Shura Committee, or the concerned tehsildars. It requires authorised collectors to carry identification, maintain transparent records, and issue official receipts. The order also prohibits coercive solicitation, harassment, obstruction of public movement, or fraudulent practices, and activates a district vigilance helpline to report suspicious activity. While acknowledging Zakat and Sadaqah as sacred Islamic obligations, the administration framed the regulation as a safeguard against fraud, misrepresentation, and the potential diversion of funds to unlawful activities—concerns reportedly flagged by security agencies.

Senior police and administrative officers have been instructed to enforce the order strictly, with violations attracting action under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023, and other applicable laws.

Yet despite these official justifications, the directive has triggered strong political and religious reactions. Zakat—calculated as 2.5 percent of surplus wealth held for a full lunar year above the Nisab threshold—is one of the five pillars of Islam and is deeply rooted in personal faith and community trust. Sadaqah, being a voluntary charity, is even more personal in nature. Critics argue that both practices are traditionally managed within communities and should remain free from administrative oversight.

Deputy Chief Minister Surinder Kumar Choudhary had on Thursday cautioned government officers against overstepping into religious domains, stressing that matters of faith must be handled with sensitivity. While reiterating the government’s commitment to transparency, he warned that such objectives should not translate into actions perceived as encroachments on religious freedoms. Officers, he said, must operate strictly within constitutional and administrative boundaries.

Opposition parties have been far more vocal. PDP legislator Aga Syed Muntazir Mehdi condemned the order as unconstitutional, asserting that it infringes upon the religious freedoms guaranteed under Articles 25 and 26 of the Constitution. He described the directive as authoritarian and demanded its immediate withdrawal. Congress leaders, including Ghulam Ahmad Mir and Nizamuddin Bhat, echoed these concerns, calling the order “provocative” and “bad in law.” Bhat argued that charity in Islam is meant to be discreet—“the left hand should not know what the right hand gives”—and that subjecting such acts to administrative scrutiny undermines their spiritual essence.

In contrast, BJP leader and Leader of the Opposition Sunil Sharma defended the order as a necessary step to prevent the misuse of charitable donations, particularly in a region where anti-national elements may attempt to exploit religious charity for unlawful purposes. He described the directive as a “welcome and praiseworthy step,” aligning with the administration’s broader efforts to ensure accountability.