Martyrs' Day: Unravelling the myth of the Mahatma

The very people who had baulked at the idea of killing Englishmen to secure their country's freedom had no qualms when it came to killing each other.

Seventy years ago on this day he fell to an assassin’s bullet. He was Bapu to millions. He was the saintly liberator, the Father of the Nation, who had brought together common folk from every corner of the sub-continent to resist the mighty British Empire. And he had succeeded without firing a single bullet. He had enabled India to defeat brute force with soul force. This was the dominant narrative, one that was more or less globally acknowledged. Yet there had been Pakistan, and the agony of Partition, a heartbreaking orgy of violence that none could satisfactorily explain. The very people who had baulked at the idea of killing Englishmen to secure their country’s freedom had no qualms when it came to killing each other. The Gandhian creed of nonviolence had ended abruptly in a spasm of bloodshed. The nation stood divided and Gandhi was ‘father’ of one half, while the other half had another ‘father’, Mohammed Ali Jinnah. Then on January 30, 1948, Nathuram Vinayak Godse fired three shots from his limited edition ‘Fascist Special’ pistol, and the Mahatma was no more.

The killing and its aftermath India and Pakistan were at war over Kashmir. Hari Singh, the Hindu king of the predominantly Muslim principality, had appealed to India for help when the Pak army transgressed his western borders. He had hurriedly signed the Instrument of Accession and the Indian army had stepped in to defend Kashmir. As the war raged, the Nehru government decided to withhold Rs 55-crore corpus that had to be transferred to Pakistan as part of the Partition deal. Gandhi undertook a fast unto death on January 13, 1948 to compel India to transfer the money. Nehru capitulated – and the Hindu hardliners were incensed. The same day a conspiracy was hatched. On January 20, their first assassination attempt ended in failure with the capture of Madanlal Pahwa, a refugee from Punjab, who promptly spilled the beans. “They will be back,” he told the police. Nevertheless, the January 30 attempt succeeded.

Nathuram Godse, Narayan Apte, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and six others were arrested and a protracted trial followed. The defence did not bring a single witness. Godse gave a long ‘why-I-killed-Gandhi’ statement, which was quickly hushed up. Godse and Apte were hanged on November 15, 1949. Savarkar and Dattatreya Parchure were acquitted, Digambar Badge turned approver, and the others served long jail sentences. There were three absconders of whom nothing is known till date.

Among the jailed conspirators was Gopal Godse, brother of Nathuram. In a 1998 interview to rediff.com, Gopal stated that he never regretted the Gandhi killing. “We killed Gandhi because he was harmful to India,” he maintained. He also insisted that Gandhi had never said ‘hey Ram!’ Apparently, that was based on Nathuram’s testimony. Later Gandhi’s aide, V Kalyanam, claimed he was standing behind him when he was shot, and hadn’t heard him say any such thing. Whether Gandhi actually said it or not can never be ascertained, but the famous last words added to the veneer of the fallen Mahatma for years to come.

When Gandhi became Father of the Nation

In 2012, a Lucknow schoolgirl wrote to the PMO seeking the origin of the honorific title ‘Father of the Nation’. A flurry of activity followed. Finally everyone realized it wasn’t a formal title and no one had conferred it. The first recorded reference was a 1944 radio broadcast from Subhash Chandra Bose to Gandhi a few months after the death of Kasturba. Gandhi, Nehru and other nationalist leaders were in prison in British India. They had been jailed in 1942 following the ‘Quit India’ resolution. Netaji was in Myanmar and Malaysia-Singapore leading the INA operations. World War II was raging and the Battle of Kohima and Imphal (Britain’s greatest battle) was in progress. Indian soldiers were fighting on both sides. Bose’s Indian National Army was allied with the Japanese. It was a do-or-die moment for Britain as well as the INA.

On June 4, 1944, Bose appealed to Gandhi on Azad Hind Radio from Rangoon, "Father of our Nation, in this holy war for India's liberation, we ask for your blessings and good wishes." Gandhi did not bless the bold venture to liberate India by waging war .The INA lost, Britain won, Bose disappeared into martyrdom, the British quit India, the Partition ripped apart the social fabric of Hindustan, and Godse finally wielded his gun. On January 30, 1948 Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru in a radio address to the nation, announced, “Our beloved leader, Bapu as we called him, the Father of the Nation, is no more.” And Father of the Nation he remains to this day.

How Gandhi became ‘Mahatma’ in 1914

The grandiose title was conferred by Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore - if our history books are to be believed. Gandhi called him ‘Gurudev’, and Tagore in turn called him ‘Mahatma’. The date: March 5 0r 6, 1915. Gandhi had landed in India barely two months earlier, on January 9, to be precise. He had until then done nothing for his motherland. How then did he merit such an overvalued epithet?Fast forward 100 years. An RTI activist sends a query to the PMO. The matter goes before the Gujarat High Court. The nation hiccups. Researchers go into a tizzy. Amid the churning of historical narratives and oral traditions some fresh facts rise to the surface.

It turns out that before Gandhi’s final exit from South Africa in July 1914 a ‘journalist’ from Saurashtra had referred to him as ‘Mahatma’. Narayan Desai’s work mentioned that a journalist from Jetpur described him thus in an anonymous letter sent to South Africa. Shashi Tharoor in his meticulously researched 2016 publication, ‘An Era of Darkness’ (p.83) writes, “There (in South Africa) his ‘experiments with truth’ and his morally charged leadership of the Indian Diaspora had earned him the sobriquet of Mahatma.” Rajmohan Gandhi, in an earlier publication described the departure of Gandhi and Kasturba from South Africa in July 1914 for India via England.

He wrote, “In different South African towns (Pretoria, Cape Town, Bloemfontein, Johannesburg, and the Natal cities of Durban and Verulam), the struggle’s martyrs were honoured and the Gandhi’s bade farewell. Addresses in Durban and Verulam referred to Gandhi as a ‘Mahatma’...” On January 21, 1915, barely two weeks after his arrival in India, Gandhi visited the Kamri Bai School in Jetpur, Saurashtra. Here the businessman Nautamlal Bhagvanji Mehta addressed him openly as Mahatma Gandhi and presented him with a citation to that effect. (Copy of the citation is in the public domain.) From that day onwards Gandhi was ‘Mahatma’ to one and all. Even without the Internet and social media this was a propaganda miracle that actually worked. Gandhi went on to become Bapu and Gandhism soon became a national fad – but the Mahatma title came first.

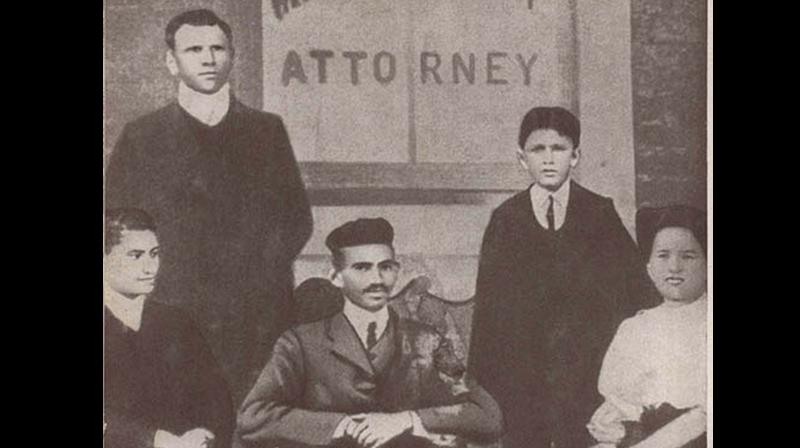

South Africa’s ‘Coolie Barrister’

In South Africa where Gandhi practised law for 21 years they called him the ‘coolie barrister’. He in turn called the indigenous blacks ‘kaffirs’. A laboriously researched book by South African professors Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed, titled “The South African Gandhi – Stretcher Bearer of Empire”, exposes some dark and grey shades of the future Mahatma’s personality. During his South African sojourn, Gandhi wrote:

• We believe also that the white race in South Africa should be the predominating race (1903).

• Should they (Indians) be assigned a permanent part in the Militia, there will remain no ground for the European complaint that Europeans alone have to bear the brunt of Colonial defence (1906).

• We have never asked for political equality...I have never asked for the vote (1914).

Gandhi’s non-Indian friends were invariably whites. What’s even more shocking is that this ‘great soul’ was indifferent to African suffering. In 1904 he wrote to the Medical Health Officer of Johannesburg, demanding the withdrawal of kaffirs from a predominantly Indian neighbourhood. During the 1906 Zulu Revolt in Natal he wrote in ‘Indian Opinion’, “It is not for me to say whether the revolt is justified or not. We are in Natal by virtue of British power. Our very existence depends upon it. It is therefore our duty to render help...” During the Boer War Gandhi served the Empire as a stretcher bearer. His political strategies included lobbying, whining, petitioning, negotiating, compromising and surrendering. He would conveniently sacrifice his core principle of non-violence whenever the Empire was at risk.

Gandhi was his own publicity agent, and a brilliant one at that. He had his biography written in 1909 by Joseph J Doke and published in England. The book titled ‘M.K. Gandhi: An Indian Patriot in South Africa’ had an introduction written by Lord Ampthill, a man who opposed every move in the direction of Indian independence. Gandhi purchased all 600 copies and had them distributed in Britain, South Africa, Rangoon and Madras. Later in the 1920s Gandhi would publish his famed autobiography.

The personal was even more peculiar than the political. In 1906, Gandhi announced his vow of celibacy. He was then 37 years old. Authors such as Kathryn Tidrick suggest that it was possibly in South Africa that he started the weird practice of sleeping with nubile nymphets to ‘test’ his self control. In May 1910 Hermann Kallenbach, a German Jew, purchased the 1100-acre Tolstoy Farm near Johannesburg for Gandhi’s use. The duo had met in 1903, shared a house from 1907-08 to 1910 and wrote letters to each other. The Indian Government purchased these letters for $1.3 million in 2012 and hid the contents. (Will someone please file an RTI?)

Gandhi’s Indian benefactors included the Maharajas of Bikaner and Mysore and the Nizam of Hyderabad. His mentor Gopal Krishna Gokhale visited South Africa in 1912 to boost his sagging political fortunes. In 1913, Gandhi formed the Natal Indian Association when he failed to get majority support within the Natal Indian Congress. Soon Indian workers in the mining and plantation sectors went on strike and Gandhi was arrested. On December 20, 1913, after his release from prison, he appeared at a public meeting at Durban in a dhoti-kurta ensemble minus the moustache. Gone was the elitist western outfit! On December 23, Gandhi wrote a letter to Marshall Campbell, “We were endeavouring to confine the strike area to the collieries only. Whilst I was in Newcastle I was asked by my co-workers in Durban what answer to give the coastal Indians who wanted to join the movement, and I emphatically told them that the time was not ripe for them to do so...” Six months later, in July 1914, Gandhi announced he was returning to India for good. And the rest is history.

(The author is IT professional, travel enthusiast and history buff)