Weaving heritage with couture

Pavithra has travelled extensively across the country, working with weavers in a learning process she insists is mutual.

Not being able to speak Hindi (or Rajasthani) didn't deter Pavithra Muddaya, of Vimor Sarees, one bit when she travelled to rural Rajasthan in 2015. That endeavour would result in a stunning collection, part of the ‘Handmade in Rajasthan' project in 2015, when the first edition of Rajasthan Heritage Week was organised in the city.

Neither the glamour of the ramp nor her prestigious clientele come to mind first as Pavithra looks back, but then, resting on laurels has never been her style. Instead, she recalls, with much mirth, her escapades in Rajasthan, of using sign language and doodles to make herself understood among the weaver community. "If you know how the loom works and you have empathy, you will be understood," she says, mild mannered and self-effacing always, despite her great success. Pavithra has travelled extensively across the country, working with weavers in a learning process she insists is mutual. Broken sentences and gestures are the medium of communication, "hands, legs, whatever works," she laughs. She also whips out her trustee sketchpad, long after sketchpads had given way to computers. "My kids would make fun of me and so would the weavers.”

Then again, the weavers she has nurtured are well past the point of formalities. "They grumble at me, asking me why I'm still stuck!" By this, they mean Pavithra's refusal to go beyond a single store in Bengaluru, although she has an extensive list of clientele, including politicians, celebrities and prestigious families. "What can I say, that's just who I am. I have a skill and I want to do something larger with it," she says. The thousands of weavers who have passed through her hands over the years have gone on to script their own success stories, taking with them the designs and aesthetics they learned at the hands of their beloved teacher. "Yes, I am that, a teacher," she agrees.

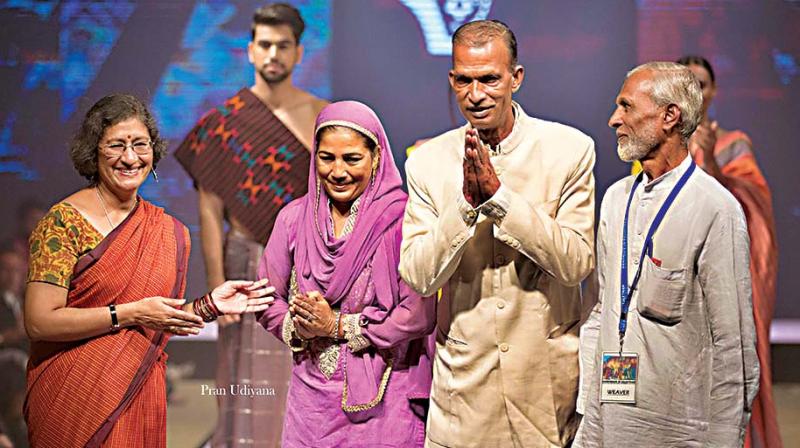

Pavithra Muddaya with Bannerghatta weavers.

Pavithra Muddaya with Bannerghatta weavers.

This is the idea behind Vimor, to mentor weavers and revive textile heritage. Our weaving traditions are largely undocumented, she explains, "upto 80%, really. A lot is said about royal textile but very little about the many, many indigenous practices that exist in the country." That, combined with the fact several of her clients walk in with their 'grandmother's sarees', only strengthened her belief in the revival and propagation of heritage weaves and motifs.

Pavithra is working towards a handloom museum, a place of inspiration for weavers, she says, where they can come to learn different techniques and aesthetic practices. She has, over the years, worked with a number of different yarns and motifs, all of them with a personal touch. The Vimor Foundation, offset of the Vimor Sarees, will work with waste silk, Pavithra explains and oral history. This involves collecting stories from senior citizens and translating those into wearable motifs. The designs they choose are usually reworked - "I don't make replicas, that's a different kind of elitism, I think, to replicate antiques and old traditions. I want my designs to have the weaver's personal touch and a more modern approach."

She refers to this as a 'mobile museum'; older weavers are shown old scraps and samples and asked to recall their own stories. "That's how we develop our design, for as I said, there is very little documentation. There will be very little left for tomorrow's generations at this rate." Research and documentation are an important part of the Foundation's work, too.

Weavers under her tutelage who have gone on to open their own stores and run successful businesses continue to thank her, "but there is no need for gratitude," she insists. "They are where I started, how I learned the craft." Her own journey began in 1974, when her father passed away. Her mother, Chimmi Nanjappa, was the first manager of Cauvery Arts and Crafts Emporium in Bengaluru. When, suddenly, they were left with nobody to rely on, it was time to put her extensive skills to use. "I was in Madras at the time," says Pavithra. "My mother would send me Channa patna silks, which I would print and send back to Bengaluru." Much of her learning was on the job, a trial-and-error process, with smaller workshops to which she was invited by the weaver community.

Her mother's association with cultural activist Pupul Jayakar would catapult them into prominence, even landing Vimor Sarees an order to design sarees for Mrs. Indira Gandhi. In 2017, she designed a collection of 108 sarees, doing pancholi work for the first time, in honour of Mrs Gandhi's centenary year. "I was shown 14 sarees for about an hour and a half and I had to recreate my designs based on my memories of those," she says.

The association with the Gandhi family continues, she says but tactfully holds back on the details. "They have treated me with a great deal of kindness, Sonia Gandhi has visited us many, many times."

There is little room for airs in Pavithra's presence, cars are parked a respectful distance away and "everyone carries their own bags," she laughs. Pavithra's own self-effacement is as much a part of her persona as her creations. "That takes a lot of work too," she says. "It's easy to be swayed, to have one's head turned by the praise and the recognition. And maybe that discernment comes with age and wisdom but I know that I need to stay true to myself." The words 'trust' and 'integrity' feature often during the conversation - "It amazes me that there are so many people who will trust me implicitly. It's a great gift and a responsibility, how many people are fortunate enough to inspire that kind of trust in another human being?" For herself, she says, "I don't have many needs and wants. I have found my purpose in life."