From church of Mary Magdalene to moonwalk

Our major missions are conducted in the full glare of live media spotlight and the world can learn in real time of our success or failure.

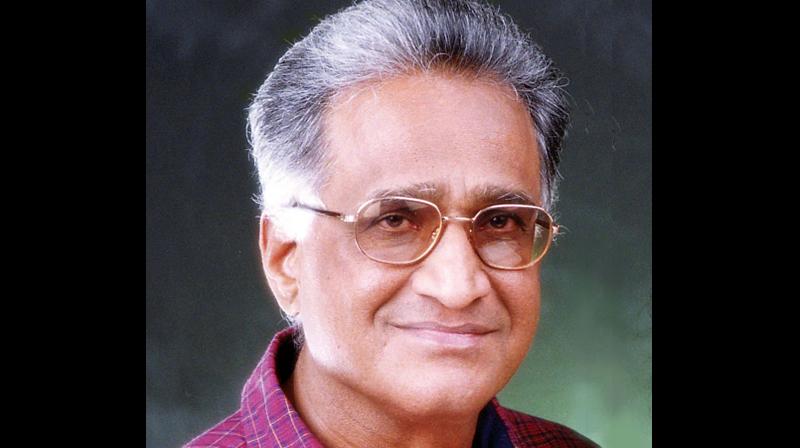

SRIHARIKOTA RANGE: For Dr Ramabhadran Aravamudan, the first rocket scientist picked by Dr Vikram Sarabhai for the Indian space programme, or C R Sathya, an engineer walking along with the cone of the French Centaure rocket precariously balanced on a bicycle in the black and white iconic picture shot in 1966, the Chandrayaan-2 mission is of a magnitude which they can never imagine.

“Chandrayaan-2 has far exceeded the vision of Dr Sarabhai. It’s a giant leap. Even he (Dr Sarabhai) would not have dreamt of such advances in technology, accomplished without external support, over the last five decades, the content of programme, and the number of people working in Isro,” Dr Aravamudan, who along with colleagues like Dr A P J Abdul Kalam, spent the early days assembling rockets inside the Church of Mary Magdalene in Thumba (near Thiruvananthapuram), told Deccan Chronicle.

Mr Sathya, whose picture with the rocket cone and cycle, by renowned French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, mirrors the humble beginning of the Indian space programme in 1960s, said though he was thrilled about Chandrayaan-2, he was unhappy about the fact that the space agency has embarked upon such grandiose programmes which Dr Sarabhai did not envisage. “We are forced to do what he (Dr Sarabhai) did not want to because we have to fall in line with global standards in space including interplanetary missions or manned missions.”

Dr Aravamudan, Sathya and their peers in the space agency attributed the success of Isro in rocketry and manufacture of state-of-the-art satellites to the unique work culture and an integrated approach to every mission with thousands of engineers working together sans any interface problems.

In his book ISRO: A Personal History, Dr Aravamudan, who served as Director, Satish Dhawan Space Centre (SDSC), Sriharikota Range, and U R Rao Satellite Centre, Bengaluru, comments on the work culture “because of its strategic nature, space technology is closely guarded by its creators. ISRO, therefore, had to develop its own technology from a scratch with great deal of trial and error. But our results have always been open for free scrutiny by the public. Failures and successes are in our field are splashed across the sky for all to see.

Our major missions are conducted in the full glare of live media spotlight and the world can learn in real time of our success or failure.”

Interestingly, the Apollo 11 landing had a key impact on India’s space programme. While the Indian National Committee for Space Research (Incospar) was set up in 1962, Isro was incorporated barely a month after the iconic Moon mission in 1969. Today it is one of the six largest space agencies with a mission of sending an Indian into space in 2022.

Reacting to the Moon landing, Dr Sarabhai was quoted as saying “Our perspective of the universe must alter fundamentally when we understand how the solar system and the important objects in it were created…The impact of this should be as significant as when man learnt that the world is a sphere and that it is not at the centre of the universe.”

Though globally Apollo 11 was an inspirational moment, Dr Sarabhai and his colleagues realised its importance at that point of time, their sights were always on taking other agendas forward: that of well-being, better livelihood, mass education and development in India.