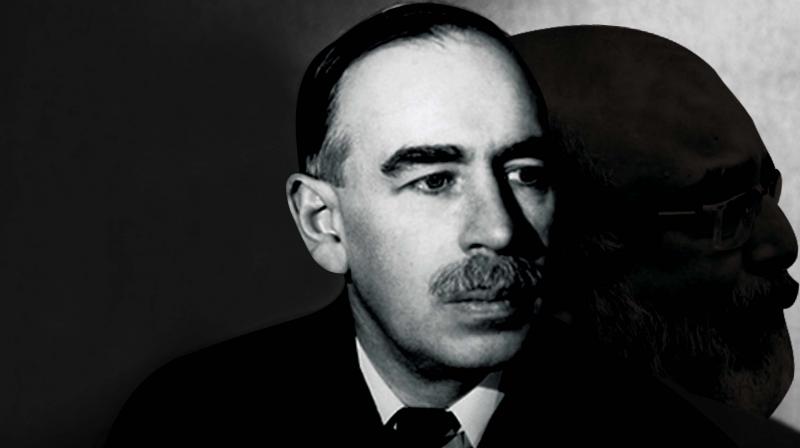

Romancing Keynes

As with every other state finance minister, Dr Isaac\'s idea has a direct connect with the pristine Keynesian line of thinking on active fiscal policy.

Finance minister Dr Thomas Isaac's capital idea to roll out a ‘Marshal Plan' to rebuild Kerala after a flash deluge left the state economy devastated might work provided the government sticks to economy in its expenditure plans. It may be interesting to watch how he translates his Keynesian maxims into praxis.

If legendary British economist the late Lord John Maynard Keynes happens to visit Kerala today, he will have a swoon seeing the swelling crowd of followers he has in the state which incidentally has a Communist party-led coalition running the government.

The latest convert to his school of thought is none other than the academic-turned-politician and state finance minister T.M. Thomas Isaac who has his ideological moorings running deep into the text and tenets of Marxist political economy. His idea to redeem Kerala from the wreckage of the so-called 'Kerala Model' by rolling out a 'Marshal Plan' - setting up of mega infrastructure projects financed solely through public spending (borrowing) a la the European Recovery Programme set in motion by the US post World War II - has the Keynesian economic thinking written all over it.

As with every other state finance minister, Dr Isaac's idea has a direct connect with the pristine Keynesian line of thinking on active fiscal policy. To say that Keynes rooted for mindless spending of public money to finance wars or on revenue regressive and cash flow negative propositions in a bid to put the economy back on a purple patch is a misnomer and elementary. Instead, Keynes supported financing high-return public investments in productive and revenue generating sectors such as roads, irrigation, power, healthcare and education, etc. that would be economically and socially rewarding. This is because such investments would create quality and high paying jobs leading to higher income, and consumer spending and above all abet capital formation (including private capital and human capital) ultimately adding to the overall growth and wealth of the economy.

This Keynesian scheme of things hinges on how the invisible hands of multiplier play out - meaning how the Re 1 spent on productive public expenditure translates into its multiples as income in the hands of people leading to an elevated level of (effective) demand. Though the textbook play of the Keynesian multiplier has its flip side, a growing body of recent research has found that it did and does work in economies feeling the heat of a slowdown, though the rate of change in economic expansion may vary. (Skeptics may please turn to IMF working paper 'Growth Forecast Errors and Fiscal Multipliers' authored by Blanchard and Daniel Leigh for a quick refresher course). But putting the borrowed money to finance unproductive projects would be counterproductive since it adds to the financial burden not only of the already stretched current generation but the generation next as well.

It is against this theoretical setting that one should look into the state government's move on recalibrating its fiscal policy by stepping up public investments through deficit financing and off-budget financing of systemically important core projects. It goes without saying that the finance minister's idea to fund mega infrastructure projects with huge sunk costs through a mix of domestic and overseas borrowings at a relatively higher capital cost - interest rate - risks fiscal slippages. But there is solid evidence to show that austerity measures such as cutting back public spending at a time of moderation in economic growth would do more harm than good for an economy in recession. Hence fiscal stimulus through prudent public spending is an effective weapon in the tool kit of policymakers to perk up the activity level.

This might have been the reasoning that prompted Dr Isaac to pitch for the Keynesian line of thinking to pump prime the economy. It is foolhardy to believe that he is expecting the textbook play of the Keynesian multiplier effect. But arguably such massive spending will definitely have a cascading effect on an economy that is flat as an ocean. Therefore, it is only logical to conceive that the Re 1 spent by the government on revenue accretive projects would translate into a conservative Rs 1.50 or Rs 2 as income for workers. If the theory works to that level in real life situation, then his idea of fiscal stimulus - revving up the economic growth through enhanced public spending - could be considered as a mission accomplished.

Naysayers and fiscal fundamentalists could argue that the state government should have gone for resource mobilisation using the weapons in the budget tool kit to finance its fiscal stimulus plans rather than borrowing more money from the market. This line of argument is based on flawed premises since it is a well-known fact that the state governments have little headroom to raise resources through taxes and levies ever since the uniform Goods and Services Tax (GST) kicked in. Further, the state of the state economy leaves the finance minister high and dry in his bid to raise budgetary resources as data shows that the government has managed to trim deficits by cutting back on expenditure, specifically capital expenditure. Capital expenditure as a percentage of Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP or the size of the economy) shrunk by a whopping 14% in 2017-18 to 1.05% from 1.64% in the previous fiscal.

Dr Isaac also has to face tough challenges in his budget math since he has to address legacy issues of blotted salary bills, pensions and finance cost. For instance, the state government shelled out Rs 0.57 or 57.14 paise of every Re 1 spent on revenue expenditure on paying salaries, pensions and interest payments in 2018-19. This is despite the economic expansion showing a reading of 7.18 per cent during the period.

Also the strict glide path of fiscal consolidation set by the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act which makes it mandatory for the states to peg fiscal deficit at 3 per cent of the GSDP and have a zero revenue deficit going forward also weighs against the state. And higher deficit readings have left states like Kerala with little space in borrowing money short-term from the Reserve Bank of India since the central bank has put a cap on borrowing under the ways and means accounts. A third window of raising money through the State Development Loans (SDLs) looks like a lost opportunity thanks to its inherent shortcomings, and it is unlikely to open wide any time sooner. This is because there is no investor appetite for SDLs since they are notoriously illiquid as they are not listed on any trading platforms and hence give no exit options for investors. Though monetising the assets of chronically sick state-owned public sector enterprises may be an easy way out, the idea risks a political backlash. Only a government with the proverbial will could find a way forward.

Considering these facts, Dr Isaac's new found love with Keynesianism throws up no surprises. However, much of the success of his plans depends on the government sticking steadfastly to economy in expenditure. As the reformist communist leader of China late Deng Xiaoping once said: "It doesn't matter whether the cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice". It may be interesting to watch how Dr Isaac translates his Keynesian maxims into praxis.