The Hague fight for Kulbhushan

How India overcame Pakistan’s arguments in Kulbhushan Yadav case at International Court of Justice.

The International Court of Justice has issued its judgment in the case brought by India against Pakistan, in the case concerning Kulbhushan Jadhav. India claimed that Pakistan was in breach of international law in sentencing Mr. Jadhav, an Indian national, to death, after a trial by a military court. ICJ found that Pakistan had violated the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (VCCR) by: (i) not informing Mr. Jadhav of his right to receive assistance from the Indian consulate; (ii) delaying the communication to the Indian consulate regarding Mr. Jadhav's detention; (iii) not allowing Indian consular officials access to Mr. Jadhav, including for the purposes of legal assistance. Consequently, the court ordered Pakistan to provide "effective review and reconsideration of the conviction and sentence". The court has also ordered Pakistan not to carry out the sentence until this review is completed.

While the judgment is relatively short, in 40 pages, it addresses several procedural and substantive objections that Pakistan raised, and Indian responses to them. Below is a summary of these objections and how they were tackled.

Preliminary objections

First, Pakistan asked the court to declare India's request inadmissible, on the ground that India had failed to draw the court's attention to the possibility of a clemency petition under Pakistan's constitution, while requesting provisional measures in this case. Second, Pakistan argued that India had failed to explore other means of dispute settlement under the VCCR, like arbitration, before approaching the court. In Pakistan's view, both of these constituted abuse of the court's procedure.

The court rejected both arguments. It held that while Pakistan's law did provide for appeals and clemency petitions, there was "considerable uncertainty" associated with them. The court also found that the VCCR did not stipulate other dispute resolution mechanisms as mandatory preconditions for approaching the ICJ.

Separately, Pakistan asked the court to reject India's claim because India had not submitted Mr. Jadhav's Indian passport as evidence of his nationality.The court rejected this argument, since both parties had treated him as an Indian national.

Applicability of VCCR

Pakistan argued that Article 36 of the VCCR, which contained the relevant obligations regarding detention of foreigners, was inapplicable for various reasons. Article 36 was inapplicable in cases involving espionage, it argued. India responded saying VCCR did not contain such an exception; the possibility of an exception was indeed discussed during the negotiation of VCCR but it was not accepted. Agreeing with the Indian argument, the court observed that it "would run counter to the purpose of (Article 36) if the rights it provides could be disregarded when (a) state alleges that a foreign national in its custody was involved in acts of espionage".

Pakistan argued that a 2008 bilateral agreement between India and Pakistan had replaced the VCCR as between them. The 2008 bilateral agreement requires "humane treatment" of persons in custody, but contains less stringent requirements than VCCR. India argued that the VCCR and the 2008 agreement co-existed, and that the bilateral agreement was not intended to derogate VCCR. The court agreed with India, noting that "given the importance of the rights concerned in guaranteeing the 'humane treatment of nationals of either country arrested, detained or imprisoned in the other country', if the parties had intended to restrict in some way the rights guaranteed by Article 36 (of the VCCR), one would expect such an intention to be unequivocally reflected in the provisions of the (2008) agreement". Since there was no such explicit provision, the court held that Article 36 continues to operate between India and Pakistan.

Violations of VCCR

Having rejected Pakistan's preliminary objections, and found Article 36 of the VCCR to be applicable, the court proceeded to examine whether there were violations.

The court first examined whether the competent Pakistani authorities had failed to inform Mr. Jadhav of his rights under the VCCR to receive assistance from the Indian consulate. Pakistan had not denied this failure. Also, given Pakistan's position that VCCR was inapplicable, the court found sufficient basis to hold that the authorities had not informed Mr. Jadhav of his rights under VCCR. This was a violation of the VCCR.

The next question was whether Pakistan had failed to inform the Indian consulate of Mr. Jadhav's detention promptly. The court noted that when Mr. Jadhav was arrested, he was in possession of an Indian passport, albeit in a false name. This provided sufficient basis for Pakistan to know at that time that he was likely an Indian national. Yet, the authorities did not inform the Indian consulate for three weeks. The court found this to be a violation of Article 36. While Pakistan argued that the requirement to inform the consulate would be triggered only upon a request by the prisoner, the court found that Mr. Jadhav was in no position to make such a request given Pakistan's failure to inform him of his rights.

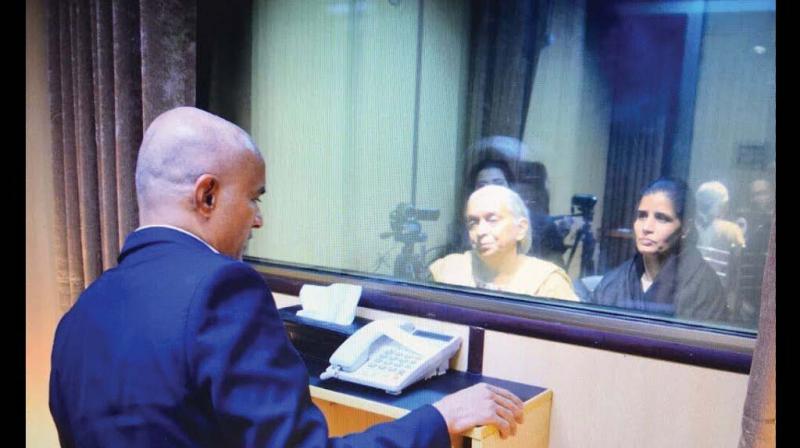

Finally, the court considered Pakistan's refusal to give Indian consular officials access to Mr. Jadhav. It argued that this was a response to India declining Pakistan's request for assistance with the investigation against Mr. Jadhav. The court agreed with India that the obligations under Article 36 were not conditional. Consequently, the court found that Pakistan had breached Article 36 in refusing consular access.

Allegations against India

Pakistan raised several serious allegations against India at various stages of this case. Pakistan argued that Mr. Jadhav was an Indian agent, sent illegally across the border with a false passport, for espionage and terrorist activities. It presented this argument both in support of its request that the court dismiss the case preliminarily, and as a justification for its violations of the VCCR. In making this argument, Pakistan referred to statements by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and national security advisor Ajit Doval, indicating that India had planned covert operations in Baluchistan.

However, given the court's characterisation of the rights under Article 36 of the VCCR as "unconditional", the Court did not find it necessary to examine these allegations. These allegations, even if true, would not justify a derogation from VCCR obligations.

Not the End

The court has ordered Pakistan to provide an "effective review and reconsideration of the conviction and sentence" to cure deficiencies arising from its failure to provide consular access. While the court did not specify how exactly the review must be undertaken, it emphasised that the review must be "effective".

Should there remain a disagreement as to the effectiveness of the review, at the end of that process, India can approach the court again, seeking a clarification on the implications of its direction.

Finally, it must be noted that the ICJ can adjudicate disputes only with the consent of both parties involved. That consent was located in an optional protocol to the VCCR, which India and Pakistan have both signed. Consequently, the court's jurisdiction does not extend to matters outside the VCCR. The court declined, for example, to examine additional claims brought by India under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. As a result, legal proceedings at the ICJ are limited to ensuring that Mr. Jadhav gets consular assistance.

(The author is a lawyer at the Geneva office of Sidley Austin LLP. All views are personal)