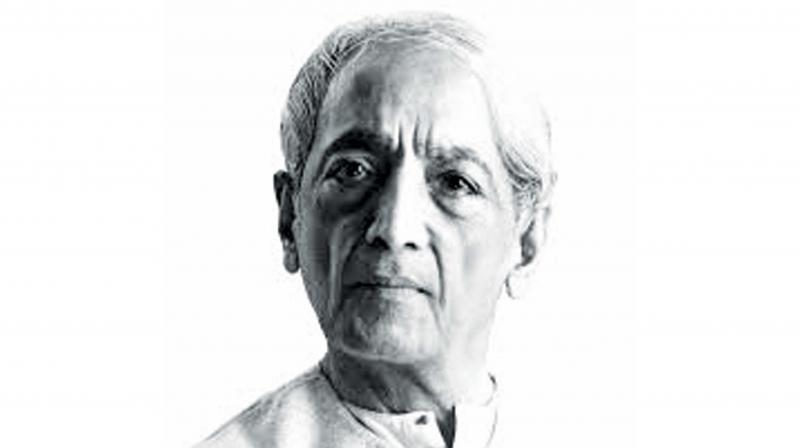

Remembering Jiddu Krishnamurti in his 125th birth anniversary year

If there was another \'JK\' as profound in Tamil Nadu, it was perhaps the Tamil writer Jayakanthan.

CHENNAI: In these days when assimilation of a caste identity to a religious identity could be so seamless, an uncommon philosopher-thinker like Jiddu Krishnamurti seems so peripheral on the earth's time's horizon.

Yet, Chennai, in particular Adyar, which was his transit home in many ways, has a place for his orbiting memories, measured and deeply contemplative talks with a gift of the gab that showed the transparency of his being as we are in the 125th birth anniversary year of JK (1895-1986), as he was widely known. If there was another 'JK' as profound in Tamil Nadu, it was perhaps the Tamil writer Jayakanthan.

'Vasanta Vihar' has lined up a several events to mark the quiet year-long commemoration of J Krishnamurti's 125th birth anniversary from May 11, 2019 to May 11, 2020 including at Rishi Valley, the school he founded; he was a radiant symbol of that universal, cosmopolitan-yet-spiritual outlook. Born in Madanapalle in Chittoor district in later day Andhra Pradesh, a coveted find of the Theosophical Society with its international headquarters in old Madras, now Chennai, he travelled and spoke in many cities of the world until his endlessly questioning spirit left his physical frame admired for its Greek-like aesthetics in Ojai in California in February 1986; however, what strikes most is his oft-repeated Socratic poser at his talks, “Sir, are you listening?”

When Dr Annie Besant had declared, “The World Teacher has arrived,” JK was not the one to get carried away. Unmindful of censure or alienation, he dissolved the “Order of the Star” as early as December 1929 - mind you amid years of the Great Depression in the West - returned all the estates he could have well commanded for the rest of his life after his initial initiation into the Theosophical Society, resigned from it the following year and walked his talk as a solitary reaper until his last breath, true to his famous dictum, “Truth is a pathless land.”

For Jiddu Krishnamurti, it was not texts, dogmas, rituals, or organised religions that mattered, but the Buddha's insight, “Be a light unto yourself.” It is self-discovery like by the Upanishad seers that points the way to emancipation, as another great Indian philosopher Dr Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, whom we all remember on September 5 every year on 'Teachers Day', would say.

Krishnamurti cannot be pigeonholed into any intellectual 'isms' or identified with any fixed positions, though his later dialogues reflect a flavour of the 'Mahayana Buddhism'. In fact, one of his oft-repeated thought used to be, “we are human beings first, not Hindus, Muslims, Christians or Buddhists.” That was the basis of his secularism, humanism and compassion for a suffering humanity in a world where there is preponderance of pain over pleasure.

A deep sense of wonderment about the miraculous and inexplicable aspects of Nature was a constant undertone in his talks. “Have we learnt to just look at a sunset?” he would ask, in a bid to disjoin the usual categories of thought that divides people, while 'intuition' brings people on to a convergence mode. “You kill a bird, there is another bird, you can't take away everything,” Krishnamurti put it poetically in what turned out to be his last public talk in Madras in January 1986.

'Physical danger'- we all instinctively and immediately respond to save oneself, as we see in the repeated man-animal conflicts in the western districts of Tamil Nadu in recent years - But Krishnamurti was always mystified by what he termed, 'psychological danger', man's response to which is clouded by inertia. Often people tend to “rationalise” it or escape from it, but not quite really confront what is the 'I' or the 'me' within that drives the whole world. Jiddu would not essay an answer to such fundamental questions, but leave it to the explorer.

Remarkably, Krishnamurti never called himself a 'Guru'. As students, many of us could hardly try to comprehend what he was trying to say. In youthful zest and defiance, we dubbed him a combo of an 'existentialist and romanticist', 'elitist' and musing 'airy nothings', though by and large it was the English-speaking middle class who would attend his talks at Adyar.

But none would disagree on one thing, that he was calling upon, albeit earnestly, subtly and very tangentially without moralising, to look inwards into the 'quality' of the human mind in a world of severe economic competition, violence and mind-boggling technologies. Jiddu was a true modernist, resented the cult of the individual and unsparingly realist in that sense, rare virtues today.

Two biographies of Jiddu Krishnamurti, one by Mary Lutyens and another by Pupul Jayakar, are equally remarkable. In his life-sketch on Pupul Jayakar, former Governor of West Bengal, Gopalkrishna Gandhi so gracefully brings out the flavours of a bygone era. The author himself has with intuitive precision titled his work, “Of a Certain Age - twenty life sketches” (Penguin Books India, 2011).

“They flocked to her official residence, ma'amed and propitiated her when she was perceived to be one of the zodiac. But with Indira Gandhi's end, word went round that the new stellar formations did not include Pupul Jayakar. That was not quite the case, but it sufficed for New Delhi's fawners of power,” is how Gopal Gandhi begins his brief memoir on Pupul Jayakar.

“The house, which had needed until then to be stretched out into its garden spaces for visitors, shrank to its core: her drawing room of which the magnetic centre was an oil painting by Anjolie Ela Menon of a sharp-chinned and white-haired man who everyone assumed to be Jiddu Krishnamurti,” writes Gandhi.

He further goes on:

“J. Krishnamurti and the Dalai Lama were in Delhi around the time of Indira Gandhi's assassination; they were to have met at Pupul's instance, over lunch, Indira Gandhi joining them. That could not happen; the trauma and the mayhem that followed had changed the environment for such a meeting.”

“The following year, Krishnamurti's health began to fall. I was secretary to Vice-President R. Venkataraman at the time. He too was an admirer of that philosopher of unconditional awareness. Pupul kept me posted - for the vice-president's information - of the phases in Krishnamurti's glowing sunset. When the ashes were brought from Ojai in the US to Delhi, Pupul had the urn kept under a flowering tree in her garden- a tree he had spent many hours under when staying with her. One part of Pupul ceased to care for life thereafter. She continued with her writing of course, and went on to complete the Indira book, as well as the new one on Krishnamurti. But in a crucial sense her life now became residual - except when she 'threw herself' into the Krishnamurti centenary celebrations.”

While observing that it is “hard to find a commonality” between Indira Gandhi and Jiddu Krishnamurti, Gopalkrishna Gandhi has beautifully captured JK's life: “If his early years had not been spared intrigue and betrayal, he had grown into his own teaching, his own living, where he taught without taking classes, spoke without making speeches, travelled without becoming a passenger. Liberated in a very unique sense, he liberated others around him. His awakened intelligence was his best friend.” These words are a fitting tribute to JK even today.