The Great Leaders' syndrome amid a political churning in Tamil Nadu

The last of them, though able to recognize people, has been ailing at his Gopalapuram residence for over a year, as the author puts it.

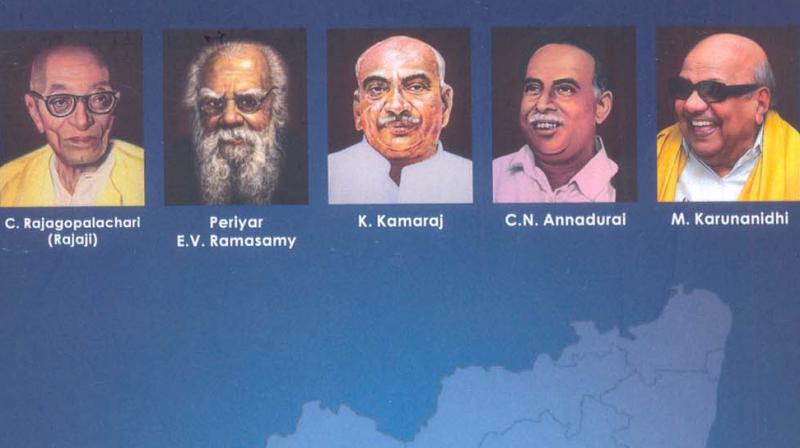

Chennai: Reading a nice little recently published book of essays titled ‘Five Great Leaders of Tamil Nadu’, by Prof N. Bakthavathsalu, a former Chennai-based Professor of History and a researcher who has contributed to the Encyclopedia published by the Tamil University, Thanjavur, one thought it was an enlightened way to focus on the ‘Great Leader’ syndrome. This issue pops up, wittingly or unwittingly, amid a silent political churning the state has been going through after former Chief Minister J Jayalalithaa’s death in December 2016.

A qualified M. Lit. research degree holder from the University of Madras, Prof. Bakthavathsalu has with a breezy brevity run through for a tech and social media savvy younger generation for whom Humanities makes no bread, the lives and times of five “Great Leaders” who have hugely impacted society and politics of modern Tamil Nadu.

Mahatma Gandhi’s ‘conscience keeper’, C. Rajagopalachari, popularly known as Rajaji, the audacious social reformer Periyar E V Ramasamy, Kumaraswamy Kamaraj, C N Annadurai and Muthuvel Karunanidhi in that order have been portrayed. The last of them, though able to recognize people, has been ailing at his Gopalapuram residence for over a year, as the author puts it.

There are some little known interesting facts about each of these leaders resurfacing in Prof Bakthavathsalu’s essays. Significantly, except for the iconoclastic Periyar, the rest were all famous Chief Ministers in their own way and who also made an impact on the national political scene in different eras.

Equally significant, from a historian’s point of view, is that these ‘great five’ in their political innings post-1920s’ have also defined the contours of political Tamil Nadu, despite the state having thrown up other big leaders too like the Justice Party founders- Dr C Natesa Mudaliar, Sir P Thyagaraya Chetty and Dr T Madhavan Nair-, and later Congress leaders like S. Satyamurthy and so on.

This slim volume on the ‘five greats’ thus underscores the basic bi-polar polity that erstwhile Madras Presidency nurtured – power alternating from the Justice Party to the Congress, and then to the two main Dravidian parties, DMK and the AIADMK, which trace their political roots to Periyar’s Dravidian Movement after the rationalist leader from Erode took over the leadership of the Justice Party. The Left parties too have played a key, catalytic role but within this band so far.

What is interesting, which people today in a hurry for political change seem to duck, is that this relatively stable two-party system that this big southern state has been able to evolve over a century, was amid two profound, turbulent and wider process of social change that took place those days, albeit slowly.

On the one hand, the Justice Party and even sections of the Congress to an extent were willing to work with the Constitutional reforms with limited suffrage that Imperial Britain had offered in doses, from the Chartered Acts of 1909, the 1919 Act and then the Government of India Act, 1935 that for the first time offered ‘provincial autonomy’. On the other hand, since Gandhi came, there was an incredible and extraordinary ‘Self-rule’ (Swaraj) wave unfolding itself, which also threw up a new crop of political leaders of all hues from the grassroots upwards.

The erstwhile Justicites and the Congress, though ideologically poles apart, were also providing a template for a non-violent change, and both movements impacted on each other as time moved. The political evolution of these ‘five great’ leaders of Tamil Nadu, whether it was Rajaji, Periyar, Kamaraj, Anna or Karunanidhi, show how diverse political traditions have intermingled despite strong differences. Beyond the caste equations, there was common humanity.

Periyar, anguished by the upper caste bias, moved from the Congress to the Justice Party through his ‘Self-Respect Movement’. Kamaraj, an uncompromising grassroots Congressman till the very end, was sensitive to the social justice tenor of the ‘Dravidian Movement’ when he stoutly opposed Rajaji’s ‘Kula Kalvi Thittam’, a controversial Educational policy that led to Rajaji’s resignation.

Annadurai’s stirring speeches in the Rajya Sabha made even Nehru take serious notice, while Karunanidhi in national interest supported Mrs. Indira Gandhi’s socialist policies. These are just few examples of how the progressive socio-political crucible of 20th century Tamil Nadu, was able to throw up ‘great leaders’ in politics, in what was the beginnings of a new charisma in the state’s politics.

Today, in the post-Jayalalithaa era, when people talk of a ‘political leadership vacuum’ in Tamil Nadu, they tend to overlook this valued historical legacy. It is not that non-Congressism is new to Tamil Nadu. One only needs to look at how the DMK made common cause with the V P Singh government, whether it was nudging the then Centre to set up the Cauvery Waters Dispute Tribunal, or in implementing the Mandal Commission report on OBC quotas at the national level.

Again, both the AIADMK and DMK have also been part of BJP-led NDA regimes at the centre. In the same breath, despite their other shortcomings, both Karunanidhi and Jayalalithaa had consistently argued and pressed for the state’s rights, irrespective of their political fates. This is an operational principle that again draws inspiration from the other ‘great leaders’ who preceded them.

Unmindful of the fiscal burdens, the AIADMK founder M G Ramachandran, despite his wavering attitude towards the Centre, had extended the limits of the welfare state, beginning with the school noon meal scheme; MGR liberalized the higher education scene that has now helped a new generation of Tamil Nadu students take advantage of the vast opportunities in the world of computers, information technology, Tamil Internet/computing, medicine and biotechnology.

While the lack of an “assertive” political leadership does not necessarily mean a ‘political vacuum’, the gains of the vision and thrust provided by the “great leaders” of Tamil Nadu is what is keeping the clock ticking. Undoubtedly a churning is on among the major OBC communities in Tamil Nadu, given the multiplicity of uncertain political developments with uncommon rapidity after Jayalalithaa’s death. No ‘great leader’ has a magic wand for exorcising all social ills.

But Prof Bakthavatsalu’s essays come as a timely reminder that the basic political framework has not been entirely lost in a forest of allegations. The Edappadi K Palaniswami- O. Pannerselvam-led current dispensation in the state knows that quite well, though their wafer-thin majority in the House has trimmed their sails.