25 years on, urban local governance still undermined in Tamil Nadu

The Constitution (74th Amendment) Act, 1992, also known as Nagarpalika Act, came into force on June 1, 1993 with an aim to strengthen grass root democracy in urban areas. Even though 25 years have gone by, participation of people and their representatives in the planning, implementation and evaluation of the programmes at local level is still a distant dream.

The prevailing model of urban governance, increasingly clouded by the presence of a range of parastatal agencies (serving the state indirectly), has resulted in reduction of the democratic spaces available for urban citizens to participate in the decision-making processes. This can only lead to further marginalising the deprived urban communities such as migrants, homeless and fishers.

In Tamil Nadu, establishing parastatal agencies towards accelerating urban development and providing services is one of the preferred approaches of development. International financial institutions heavily influence the decision-making process through the parastatal agencies while implementing people-welfare schemes, circumventing democratic processes in the ULBs. This trend has resulted in the transition from a welfare-based to market-centric reforms in urban governance.

Increasingly, parastatal agencies are bestowed with powers to address the basic needs of the citizens, which is primarily the Constitutional mandate of the State. Key focus areas including urban planning, infrastructure, finance, water supply and sewerage, transportation and water bodies are being implemented by various parastatal agencies like the Tamil Nadu Urban Infrastructure Trustee Company Limited (TNUITCL), Tamil Nadu Urban Finance and Infrastructure Development Corporation (TUFIDCO), Tamil Nadu Urban Infrastructure Financial Services Limited (TNUIFSL), Tamil Nadu Water Investment Corporation (TWIC) and Chennai Rivers Restoration Trust (CRRT).

The roles of these parastatal agencies are overlapping the functions of the urban local bodies thereby hindering the implementation of the Nagarpalika Act in its true spirit. While the State Government claims that such overlapping is sometimes necessary to improve the quality of services and to minimise delays in implementation of processes, the participation of the citizens in the decision-making process is undermined.

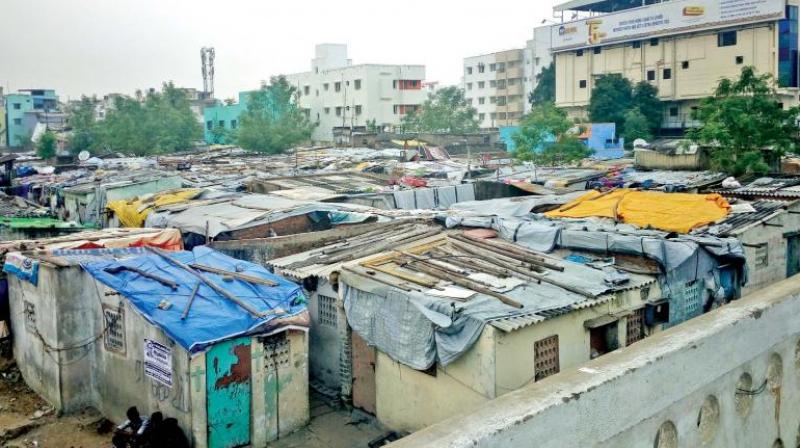

Further, the impact of the limited role of the ULBs can result in disparities of services among the poorest of the poor as provision of infrastructure facilities to areas of habitation of the urban poor could be viewed 'economically' unfeasible as basic infrastructure projects are funded based on the feasibility and credit worthiness of the projects proposed. This could worsen the quality of living of the deprived urban citizens.

After the enforcement of the Nagarapalika Act, 'Slum Improvement and Upgradation' and 'Urban Poverty Alleviation' are now under the jurisdiction of the ULB. The state municipal laws were also amended to ensure that the changes were incorporated. However, these amendments made in the state municipal laws are only on paper and not implemented. The Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Board (TNSCB) continues to be the nodal agency for improvement of informal settlements and the role of the ULB in this regard is still not clearly demarcated.

The decreasing democratic spaces even after 25 years of enforcement of this legislation has prevented the roots of democracy from reaching out to the urban citizens, especially those in the marginalised segment.

(The writer is the founder of Information and Resource Centre for the Deprived Urban Communities, a community-centric information hub in Chennai designed to educate and empower the deprived urban communities.)