Modified polio vaccine may help extend life for brain cancer patients

For most patients whose glioblastoma has recurred after treatment, the average survival is 12 months.

Some 21 percent of patients with advanced brain cancer treated with a modified polio vaccine were alive after three years, compared with 4 percent of patients with similar tumors who received standard therapies, U.S. researchers said on Tuesday.

The findings, published online in the New England Journal of Medicine, are the latest update on an experimental cancer vaccine developed at Duke Cancer Institute in Durham, North Carolina, for patients with glioblastoma, a deadly form of brain cancer.

For most patients whose glioblastoma has recurred after treatment, the average survival is 12 months. Treatment typically involves a mix of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation and targeted treatments.

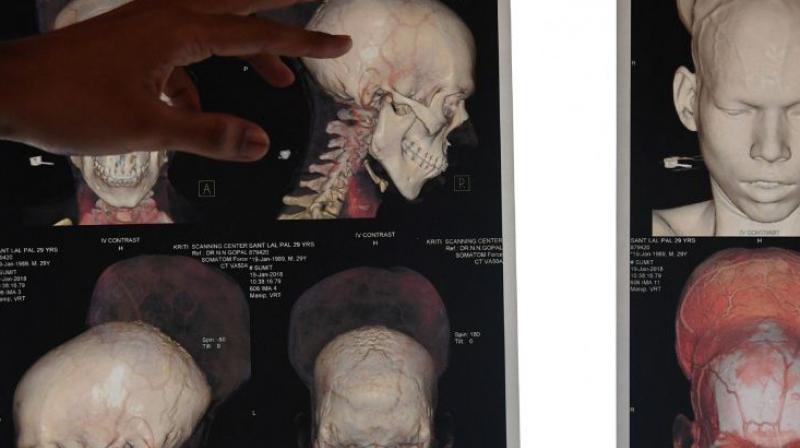

The experimental vaccine involves a genetically modified form of polio, which is infused into the brain tumor through a surgically implanted catheter. The vaccine works by provoking the immune system to specifically target tumor cells.

The phase 1 trial was designed to find a safe dose. It involved 61 patients treated with the poliovirus vaccine whose progress was compared to historical records of similar patients treated with standard therapy. Several patients who received a higher dose of the vaccine had brain swelling and seizures, and most had their dosage reduced.

The vaccine showed a dramatic response in some patients, with two remaining alive at least 69 months. But most did not benefit and many - 69 percent - had side effects attributable to the vaccine.

For all 61 patients, half were still alive at 12.5 months, a measure known as median overall survival, compared 11.3 months in the control group.

For patients who survived two years, the impact of the cancer vaccine became more evident.

At two years, 21 percent of vaccine-treated patients were still alive, compared with 14 percent of the historical control group. That rate remained stable at three years, with 21 percent of the vaccine patients still alive, compared with 4 percent of the control group.

“Similar to many immunotherapies, it appears that some patients don’t respond for one reason or another, but if they respond, they often become long-term survivors,” Dr. Annick Desjardins, one of the study authors, said in a statement.

Desjardins and several of the researchers hold patents to the treatment, which Duke has licensed to Istari Oncology, a startup company. A phase 2 study is underway.