Untranslatable Souls: The Radical Art of Literary Translation

Heart Lamp proves literary translation is more than technical.

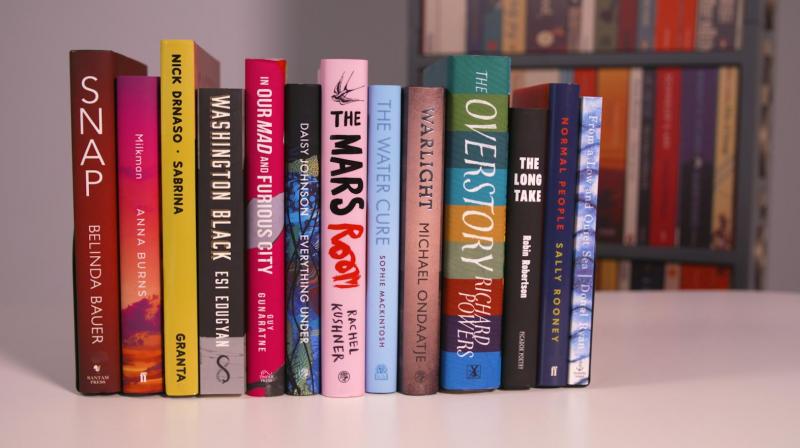

Representational image

Translating literature, from Dostoevsky to Banu Mushtaq, demands more than linguistic accuracy—it requires a writer’s instinct, cultural awareness, and radical sensitivity to language. Recent controversy over poor translations of Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov highlights the renewed relevance of translation criticism. The 2025 International Booker Prize, awarded to Heart Lamp, a collection of Kannada short stories by Banu Mushtaq translated by Deepa Bhasthi, marks a historic first: the first win for a short story collection and an Indian translator.

Heart Lamp proves literary translation is more than technical. Bhasthi selected 12 stories from Mushtaq’s 50+ tales, capturing the emotional lives of southern Indian women. Prize judge Max Porter called it “a radical translation… genuinely new for English readers.” This radicalism lies in both content and approach.

Translation, with sensitivity and imagination, is literary creation. As Vishnu Khare said, “Translating great literature demands as much genius as creating it.” Literary giants like Agyeya, Raghuvir Sahay, and Nirmal Verma excelled in translation, capturing a work’s soul through nuanced language.

Bhasthi’s Heart Lamp uses “an English with a Kannada hum,” or “translating with an accent.” She avoids simplifying Kannada for Western readers, aiming to “expose the reader to new words,” as she told Scroll.in. This resists exoticism and cultural flattening, making translation storytelling.

In India’s Hindi heartland, Kabir’s mysticism, Ghalib’s ghazals, or Phanishwarnath Renu’s Bihari realism resist easy translation into English. Poor translations can be destructive—one Hindi translation turned “steaming jungles of Indonesia” into “flowing forests,” and another mangled a metaphor about energy redirection into a literal transfer.

In contrast, Heart Lamp celebrates “a multiplicity of Englishes,” preserving the original’s vitality. Booker judge Sana Goyal noted the stories’ range, from quiet to comic, rooted in women’s lived resistance through memory.

Bhasthi joins translators like Gregory Rabassa, Anthea Bell, and Tim Wilkinson, who co-created works. Rabassa’s translation of One Hundred Years of Solitude was preferred by Márquez himself. Bhasthi’s fidelity ensures Heart Lamp resonates in both Kannada and English.

This Booker win, elevating Kannada fiction to world literature, reflects a shift—validation now flows from South India outward. As Mushtaq said, “Literature is a sacred space where we live inside each other’s minds.” Translation, when done well, enables this, making it not just wordplay but world-making and, in Heart Lamp’s case, world-shaking.

Written by: Hariom, University of Hyderabad, Intern.

Listicle: All Indian Booker and International Booker Prize Winners (Up to 2025)

1. Arundhati Roy – The God of Small Things (1997) – Booker Prize

First Indian to win the Booker for her poetic Kerala-based novel.

2. Kiran Desai – The Inheritance of Loss (2006) – Booker Prize

A moving exploration of migration, loss, and identity.

3. Aravind Adiga – The White Tiger (2008) – Booker Prize

A satirical take on class and ambition in modern India.

4. Geetanjali Shree (Author) & Daisy Rockwell (Translator) – Tomb of Sand (2022) – International Booker Prize

First Hindi novel and Indian-language book to win the International Booker.

5. Banu Mushtaq (Author) & Deepa Bhasthi (Translator) – Heart Lamp (2025) – International Booker Prize

First Kannada book and short story collection to win the prize.

( Source : Deccan Chronicle )

Next Story