Book Review | In ‘Songs’ Of City, An Unequal Music

Lindsay Pereira’s first two novels were both set in Mumbai, the city where he grew up. His debut novel, Gods and Ends, was a cacophonous melody of sound, set in a Goan neighbourhood in the city, admirably alive to the texture of Indian English in its various guises

What do novelists turn to the short story for? Perhaps for practice, as in Ray Bradbury — who wrote one a week as a kind of riyaaz ahead of the more serious business of novel-writing. Others might claim, like Borges did, that the novel in any case is nothing more than a series of shorter stories; that an “abundance of pages is a promise of boredom or mere routine”.

Lindsay Pereira’s first two novels were both set in Mumbai, the city where he grew up. His debut novel, Gods and Ends, was a cacophonous melody of sound, set in a Goan neighbourhood in the city, admirably alive to the texture of Indian English in its various guises. One can forgive the unevenness of his second — The Memoirs of Valmiki Rao — for the writer’s willingness to venture into uncomfortable territory and expand and complicate the canvas of the city which features so prominently in his work.

In these short-stories, we see a different side to the writer. The opus that was Valmiki Rao leading us, perhaps understandably, into a collection that might perhaps constitute a clearing of the throat. Here, Pereira varies his line and length: the bombast and narrative plenitude of his earlier works gives way to a sparer style — but to mixed results.

On certain occasions, as in the opening piece featuring a god-fearing antique dealer, these stories offer snapshots that bring us into our cultural present but might frustrate readers averse to loose ends. Yet too often big cities in fiction can feel pre-fabricated rather than genuinely realised: some of the depictions here fall short of the standards Pereira has set for himself. The Chor Bazaar antique dealer, fat and conniving, is an easy caricature; the depiction of a dead-eyed saleswoman conducting insurance fraud scams from a nocturnal call-centre a heavy-handed portrait of neoliberal India. And why do only lower-class men scratch their balls in Indian writing?

Two excellent stories, nestled between the warp and weft of the city, make me wish I tempered some of these complaints: in the first, an old Parsi man ruminates on his strained relationship with both his wife and his broken dream of conducting the Bombay Symphony Orchestra. In another, a police sketch artist memorably leaves in the features of Pamela Anderson in every drawing he makes.

The best stories in the collection arrive at the very end, as if the writer were warming up with every passing effort. Here, we foray further afield to Paris and London. Loss, migration, and the metabolising function music plays with regards to both are prominent preoccupations throughout the collection; in its final short story, which also lends the book its title, we see a grieving Sikh family in Southall during the sixties, tossed into the rolling tide of Beatlesmania. It is a touching ode to both music and the disorienting modes of belonging that so mark the Indian diasporic experience. Though not all the stories in this collection work to equal effect, they suggest a writer admirably exploring newer, bolder horizons. His readers are all the better for it.

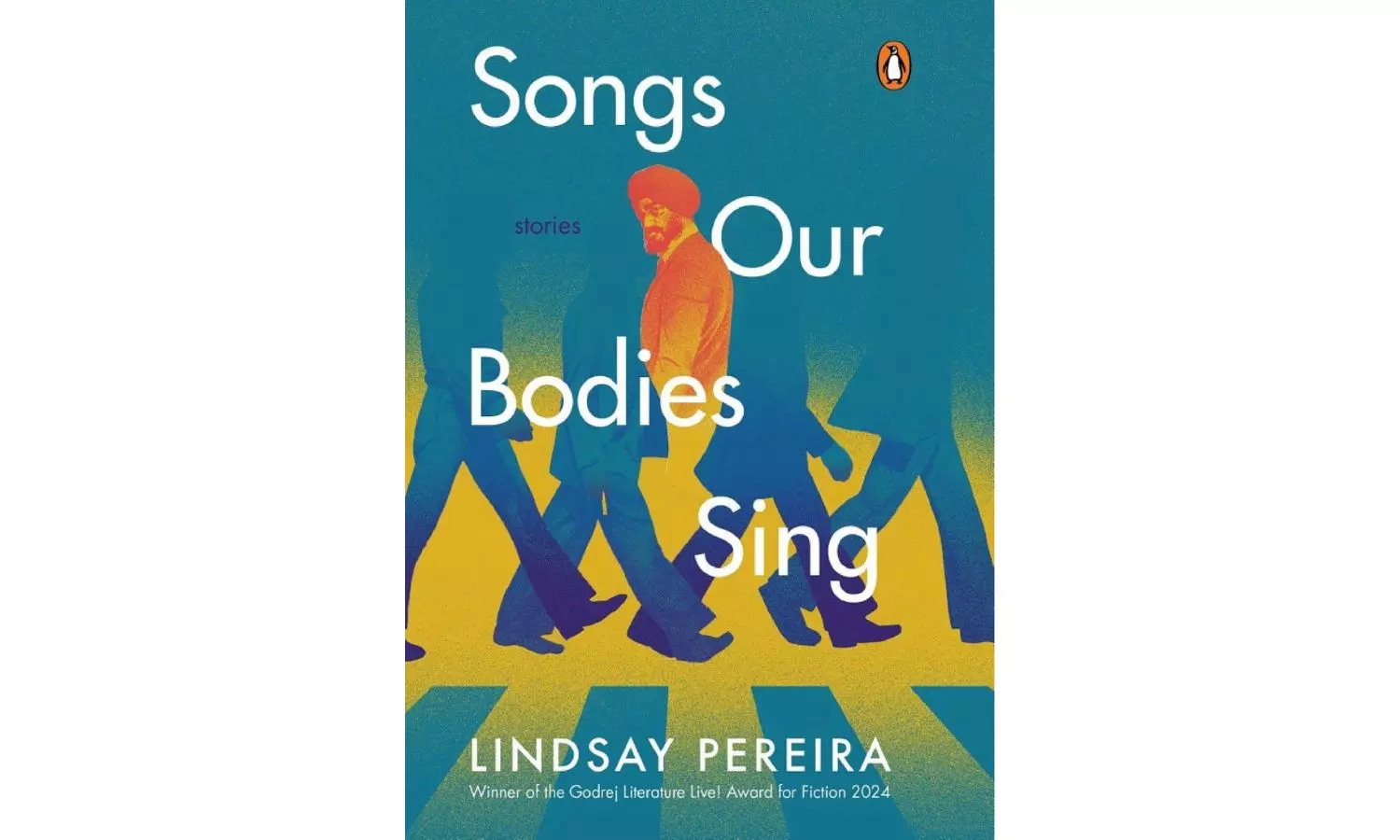

Songs Our Bodies Sing

By Lindsay Pereira

Penguin Vintage

pp. 256; Rs 499