Malayalees played the part to script saga of Singapore

Anitha had found in her research that there's little documentation on the migration and evolution of Singapore Malayalees.

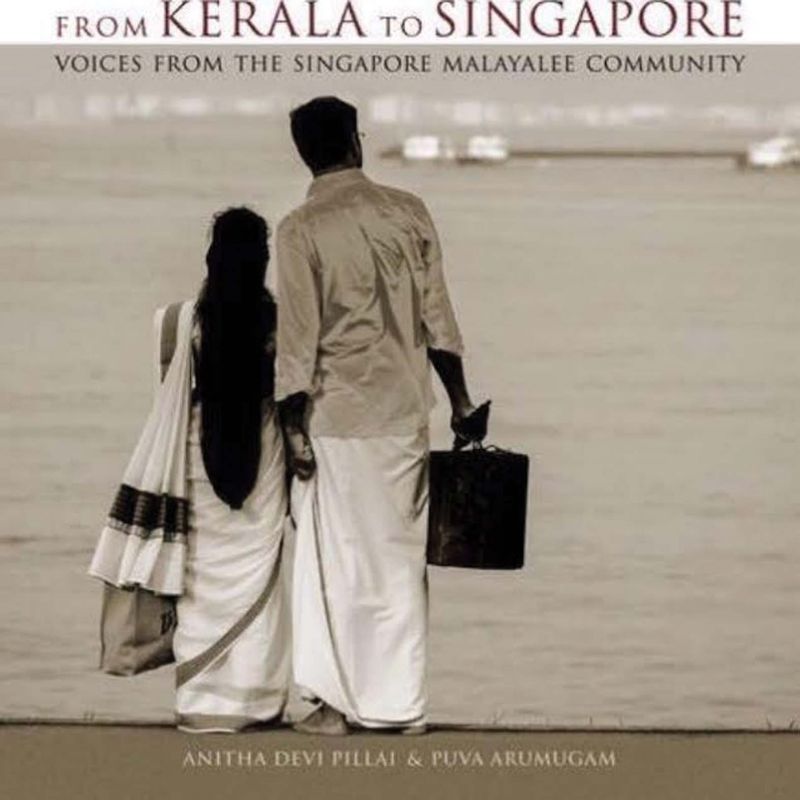

More than 130 interviews were conducted, each lasting an hour. About 400 photographs were collected and dozens of family trees drawn up. It was not easy for Anitha Devi Pillai and Dr Puva Arumugam to write ‘From KeralaTo Singapore: Voices from the Singapore Malayalee community’. Anitha, a fourth generation Singapore Malayalee, who has published several articles on the topic, had found in her research that there’s little documentation on the migration and evolution of Singapore Malayalees. “Malayalees are the second largest Indian community in Singapore and members of the community have made important contributions in the evolution of modern Singapore. So this book is as much an account of the Singapore-Malayalee community as well as an account of Singapore’s history,” Anitha writes in an email interview.

Anitha has a PhD in Applied Linguists and is teacher educator by profession. Her co-author is a Singapore born Indian playwright and poet with a PhD in Theatre and Cultural Studies. Discoveries the two had made while documenting stories of hundreds would continue even after the book got published. “For instance, I find out that my interviewees are related to one another or that someone’s aunt’s or uncle’s picture has been included. As a minority group within the minority Indian race, it is a tightly knit community,” Anitha says. One of her interviewees recalled that she used her knowledge of Malayalam to learn Malay. She’d found several similarities between the two languages.

“Although they were a small community, Malayalam was one of the languages used in a banner announcing a strike by Singapore Factory and Shop Workers’ Union in 1955. Potential political candidates delivered speeches in Malayalam as well in the early 1950s.” The community also boasts of having the only Malayalam daily newspaper outside of Kerala in the 1930s called Kerala Bandhu. The paper stopped operations in 1977. By then it was known as Malaysia Malayalee. Anitha could pour out scores of these community anecdotes. Like how it set up several libraries to serve the needs of the bachelors, who had moved to Singapore such as Naval Base Kerala Library and Udaya Library. “Perhaps my favorite anecdote and discovery in researching on Singapore Malayalees was that after Singapore obtained her independence, they launched their first definitive series of stamps. The theme chosen was Masks, Dances and Musical Instruments. The stamps reflected the culture of the three main communities, Chinese, Malayand Indians.

The two stamps that depicted the Indian community were one on Kathakali mask and the other a Bharathanatyam dancer, modelled after Mrs Shanta Bhaskaran, from Kerala. Despite being a minority community within the minority Indian race, we must have played a significant role to be featured in the first definitive series of stamps launched by Singapore in 1968, soon after independence.” Anitha’s research had shown her that people identify themselves as Malayalee in different ways. Some may not speak the language, but identify closely with the culture. Anitha herself can’t read or write in Malayalam but she speaks the language with ease. She grew up watching a lot of Malayalam plays, when there was limited access to movies and songs. That changed with cable television and other advances in technology. “The growing migrant community has actively created more opportunities for the youth to keep the language alive.” The story of Singapore should not just be told by the government. It is everybody’s story, said Prof. Tommy Koh, ambassador at large, who launched the book.