Exploring the roots of Bengali exceptionalism

The British had their capital in Kolkata and Bengalis were among the first to receive the benefits of Western education and enlightenment

Every community or people has its own complex set of attributes, of excellences and idiosyncrasies, of foibles and faultlines. It has its share of grand and ignoble history, cultural quirks and civilisational signposts. Bengalis, the largest ethno-linguistic group in the world after the Han Chinese and Arabs, are no different.

But maybe they are particularly worthy of analysis because of their singular place in the history of the subcontinent during and in the aftermath of the British Raj.

It’s what a Bengali, filled with his sense of singularity and uniqueness in the world, might tell you without the slightest hint of irony. There is no dearth of irony, though, in Sudeep Chakravarti’s The Bengalis: A Portrait Of A Community.

The Bengalis: A Portrait Of A Community

The Bengalis: A Portrait Of A Community

By Sudeep Chakravarti Aleph Rs 799; pp. 496

Indeed, the book is a brilliant tour de force, a stunning biography of a community — as much a scholarly exploration of its history, evolution and culture as it is a witty takedown of its absurdities and its puffed-up sense of the self.

Nothing illustrates the Bengali’s colossal self-regard as that inimitable phrase, “non-Bengali” or “Obangali”. It is our generic appellation for a person who belongs to any other community. “It is closer to non-person than persona non grata, but that would be splitting hairs, which the Bengali can perform even when asleep,” writes Chakravarti, who dwells at length on the typical Bengali’s absolute conviction that he is culturally and intellectually superior to such lesser mortals as “Obangalis”. Hence, every other community, and especially those who reside in Bengal or in its vicinity, is dismissed with contempt and a suitably derogatory epithet. The Bihari is a “khotta”, the Odiya, Uré, the Assamese, Ashami (which also means convict in Bangla), and the most loathsome of all, the Marwari — the “duplicitous” business people whose forefathers betrayed Siraj-ud-daulah to Robert Clive and the John Company in 1757 — the utterly reprehensible “Mero”, or, if you happen to be from East Bengal (now Bangladesh), the more lilting, “Maura”.

Of course, part of the Bengali snobbery against what the author prefers to call the “not-Bengali” lies in the fact that Bengal was at the forefront of modern subcontinental aspiration in colonial India. The British had their capital in Kolkata (then Calcutta) and Bengalis were among the first to receive the benefits of Western education and enlightenment — a process that contributed to the so-called Bengal Renaissance. For about 100 years from the late 18th century onwards, Bengal witnessed a remarkable cultural efflorescence, spawning a number of writers, thinkers, social reformers, educationists, and so on. The Bengali’s smug assumption that he is the centre of a largely brutish world is a throwback to those glory days.

Chakravarti, a veteran journalist and author of several works of non-fiction and fiction, explores the roots of Bengali exceptionalism at some length. As a subjugated people often ridiculed by its colonial masters, it was perhaps natural that the community would be aggressively proud of its achievements and refinements. The Bengal Renaissance, one of its supreme distinctions, also led to another quintessentially Bengali cultural construct: the bhadralok, the polite, civilised gentlemen, as opposed to the chhotolok, the little (or lesser, inferior) people — rough of manners and crude of taste. The bhadralok is at the top of the Bengali social heap, writes Chakrabarti, although even this refined universe has numerous stratifications such as bonedi (old aristocracy), moddhobitto (middle class), uchcho-moddhobitto (upper middle class), and nimno-moddhobitto (lower middle class) — that vast underclass populated, in the main, by clerks or those with small salaried jobs.

Chakravarti’s “Banglasphere” encompasses Bengalis in West Bengal and elsewhere in India, the people of Bangladesh and the Bengali diaspora scattered the world over. Their modern history is fraught, marked as it is by two bifurcations of Bengal — one in 1905 by Lord Curzon, Governor-General and Viceroy of India (this was reversed in 1911), and the other in 1947 at the time of Partition. Both divided a people along religious lines — Hindus and Muslims cast into western and eastern parcels of the land. What is now Bangladesh underwent a third round of convulsion and bloodletting when it threw off Pakistan’s yoke and came into being in 1971. In a sense, Chakravarti is ideally suited to tell the story of a people riven by history and religion. His family has deep roots in Opar Bangla — the Bengal on the other side, as opposed to Epar Bangla, the Bengal on our Indian side — and part of his extended family are Muslims in Bangladesh. Indeed, the narrative is the richer for his at times emotional, and always acutely observed, personal anecdotes.

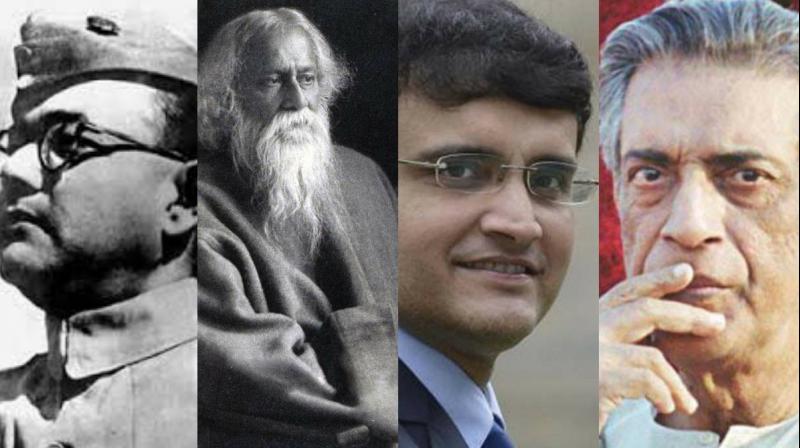

Much of The Bengalis is devoted to the community’s cultural landscape — its prejudices, racism and misogyny, its glorious tradition of adda and the verve of its patois. It talks about the Bengali’s obsession with food, his often virulent politics, the Naxal movement that started in 1967, and the growing tide of radicalism in Bangladesh. It dwells on the Bengalis’ fierce pride in their icons and revolutionaries, the adoration heaped on a Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, a Rabindranath Tagore, a Satyajit Ray or a Sourav Ganguly. But the football-mad Bengali venerates other heroes too. He will claim a Pele or a Maradona as his own and become quite frenzied with joy if they happen to visit Kolkata for a day.

Charkravarti’s tone is wry and he is particularly delightful when he dwells — albeit with the slight uppityness of the mission school educated — on the linguistic pratfalls of our fellow Bongs — the travel-mad Bengali enjoying the “sinikbewty” of a “seebitch”; or, roaming Darjeeling in bracing spring weather clad in “pullobhar” and “mankicap” (monkey cap, the Bengali’s fail-safe shield against irreversible head cold); the Bengali who talks of “labhmarrej” or follows up a question in Bangla with its corresponding English interrogative — a “hoayi” (why) or a “hoaat” (what) — for added significance. (I was reminded of Nihar Ranjan Gupta’s fictional detective character Kiriti Roy who was often wont to say, “Kintu keno? Why?” Chakravarti is spot on.)

Extensively researched, deeply felt and engagingly narrated, The Bengalis is a compelling read. The many editing errors could have been avoided. But that apart, the book will strike a chord with every Bengali. And perhaps some not-Bengalis too.