Thakur from Ballia: Biography in making

The authors also speak of how and why the then Karunanidhi-headed DMK government in Tamil Nadu was dismissed.

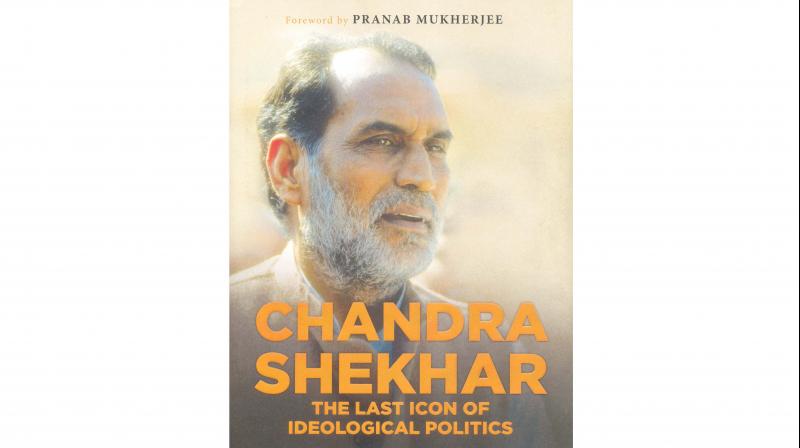

CHENNAI: It is historic. But to shorthand the story of India’s eighth Prime Minister, Chandra Shekhar, as being the ‘Last Icon of Ideological Politics’ is a bit of a stretch.

For one reason, the distinguished authors of this book, Harivansh, who had worked in Chandra Shekhar’s PMO and Ravi Dutt Bajpai, whose work display an enormous amount of research and seemingly driven to set the record straight, have in their subtitle sought to prejudge contemporary history.

One is only reminded of Karl Popper’s arguments that predictions in the social sciences - that includes History as well- are fundamentally unscientific. Today, even the Marxists would accept this proposition.

In partly explaining their rationale, the authors rue that people from humble origins “who have succeeded in holding the highest political office in the land” - have not been sufficiently acknowledged by the Indian elite, “who have a tendency to undermine people from Hindi-speaking regions.” But this is not always true, for India’s freedom struggle set the template for Indian modernization too, spawning a pan-Indian eco system of the ability to appreciate a galaxy of stalwarts in all fields.

To limit that larger vision to the halo around the PMO is disappointing, for even in post-Independent India, people have as much adored a Rajendra Prasad, Lal Bahadur Shastri, Jagjivan Ram, JP and the like, though their lives may not have caught the popular imagination with the intensity their individuality deserved.

Nonetheless, the authors’ preface does not detract from the larger value of this book on one of the extraordinary and decisive political leaders India has seen, rising from a lower middle class background from Ballia in Uttar Pradesh- even if upper caste by his Thakur clan credentials-, Chandra Shekhar.

Politically astute, sharp, even if rustic in his articulation, and for all his obduracy he was a committed Socialist from the beginning of his political career; his sensitivity to the big picture of India’s cultural diversity, secularism, the dissent in India’s intellectual traditions, right from Charuvakas who questioned the Vedic tradition and beacons of wisdom from Buddha to Christ to Mahatma Gandhi, one who was in and out of the Congress, spanning an extraordinary parliamentary career starting from 1962, his political sagacity that shone in times of crisis, all these and more show he was no straw man. And leaders have had their fair share of controversies as well, his use of Chandra Swami for instance.

For the man, as the authors recount, who could tell the Akali Dal faction leader Simranjit Singh Mann that he had a “bigger and even deadlier sword” at his ancestral home in Ballia, when the Sikh leader at a meeting during the Punjab crisis told him his sword was “very lethal”, Chandra Shekhar was unafraid to speak his mind in the best democratic traditions.

As the ‘Young Turk’, Chandra Shekhar stood with Indira Gandhi in her ideological fight against the old guards in the Congress. A complex relationship that evolved between the two and the ultimate irony of he being one of the ‘Opposition’ leaders arrested on the night Emergency was declared by her along with JP and others, has been penned by the authors with a lot of insider insights and vigour.

And when Morarji Desai, after becoming the first non-Congress Prime Minister in 1977, wanted to withdraw the security and the bungalow from Indira Gandhi in New Delhi, the authors recall that Morarji was trying to go by the rules. Desai even opined that the houses allotted to the families of Zakir Hussain and Lal Bahadur Shastri and Lalit Narayan Mishra, would be cancelled to enforce the rule.

However, as the authors write: “A defiant Chandra Shekhar then reminded Morarji of the irony and futility of withdrawing government housing from someone whose family had donated Swaraj Bhawan and Anand Bhawan to the nation and who had been the Prime Minister for the last eleven years. After a lengthy debate, Morarji finally conceded that he would let Indira Gandhi retain her official bungalow only because Chandra Shekhar was so insistent.”

Such anecdotes reveal that despite serious differences with various political leaders - even during his PSP (Praja Socialist Party) days he accepted Acharya Narendra Deva as his political ‘Guru’ and not the flamboyant socialist Dr Ram Manohar Lohia-, including with Rajiv Gandhi as Opposition leader (the unforgettable game-changing episode of two Haryana police constables snooping on PM’s house), Chandra Shekhar was no petty-minded politician. Yet, he fought ‘personality cult’ in politics, a plank that the anti-corruption movement would later appropriate.

By all accounts, Chandra Shekhar proved to be an effective Prime Minister, in the eight months after the V.P. Singh government fell on November 7, 1990- he did not fail to point out how confused the Raja of Manda could be in office-, till third week of June 1991, a month after the tragic assassination of former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi on Tamil Nadu soil-. The authors disclose that Chandra Shekhar cautioned Rajiv Gandhi to “be careful of his personal safety.”

Perhaps, Chandra Shekhar’s best moments as PM was when he ably handled the BoP and foreign exchange crisis in 1990, when the unseemly prospect of a sovereign default started at India and RBI had to ship our gold to save the country’s prestige. His logic was simple and direct, the country had to do it just as it is common in Indian households to pledge family silver to meet a crisis, if we risk excessive external borrowings and live beyond our means.

Whether it was allowing the controversial refueling of the US planes on Indian soil that gave his government a leverage to negotiate with the IMF for a much-needed financial window, his reshuffling of the top echelons in the Finance Ministry with a new dynamic team of Finance Secretary, S.P. Shukla, the brilliant S Venkitaramanan as RBI Governor, an outstanding economist in Dr Manmohan Singh as advisor to the PM, C Rangarajan as Deputy Governor of RBI, Deepak Nayyar, incumbent Chief Economic advisor, and last but not least Gopi Arora who led the Indian delegation to the IMF, his handling of this major crisis stands out.

Chandra Shekhar’s ‘blunt talk’ with Nawaz Sharif after Rajiv Gandhi’s funeral in Delhi, on Pakistan’s responsibility when a crisis was brewing over the LoC, is a pointer that that concept of ‘strategic strikes’ is not something new. The authors say that Chandra Shekhar would have then even resolved the Ayodhya issue had he stayed more. Quoting his then Law Minister, Dr Subramanian Swamy, they speak of how the then PM made RSS call off the ‘Kar Seva’ scheduled for December 1990, “by deputing Chandra Swami to engineer a rift between the VHP and the assembly of saints in Ayodhya”. Chandra could never subscribe to RSS’ policies.

The authors also speak of how and why the then Karunanidhi-headed DMK government in Tamil Nadu was dismissed in the wake of escalation of pro-LTTE activities in the state; but that chapter is incomplete without the other side of the story being told. In fact, many years later, Karunanidhi made a detailed statement in the State Assembly on the Centre’s and DMK’s role vis-a-vis the LTTE and other Sri Lankan Tamil militant groups.

Though the book in terms of its documentation scope is absorbing, illuminating and tries to give a fresh perspective on Chandra Shekhar, there are bits and pieces of information that are repeated across chapters.

Yet, the gestalt of this remarkable rural grassroots man ascending the PM’s Gaddi is yet to emerge.