A life not seen through rose-tinted glasses

Sanjay Dutt is the third in my series of “untold stories†about famous film personalities.

Sanjay Dutt is the third in my series of “untold stories” about famous film personalities. When I was writing about Rajesh Khanna after he passed away, most of the people wanted to talk and share stories about “Kaka”. During the research on Rekha, nobody wanted to talk beyond her films. And in the case of Sanjay Dutt nobody wanted to talk about him at all. And now Sanjay himself, doesn’t want us to talk about him.

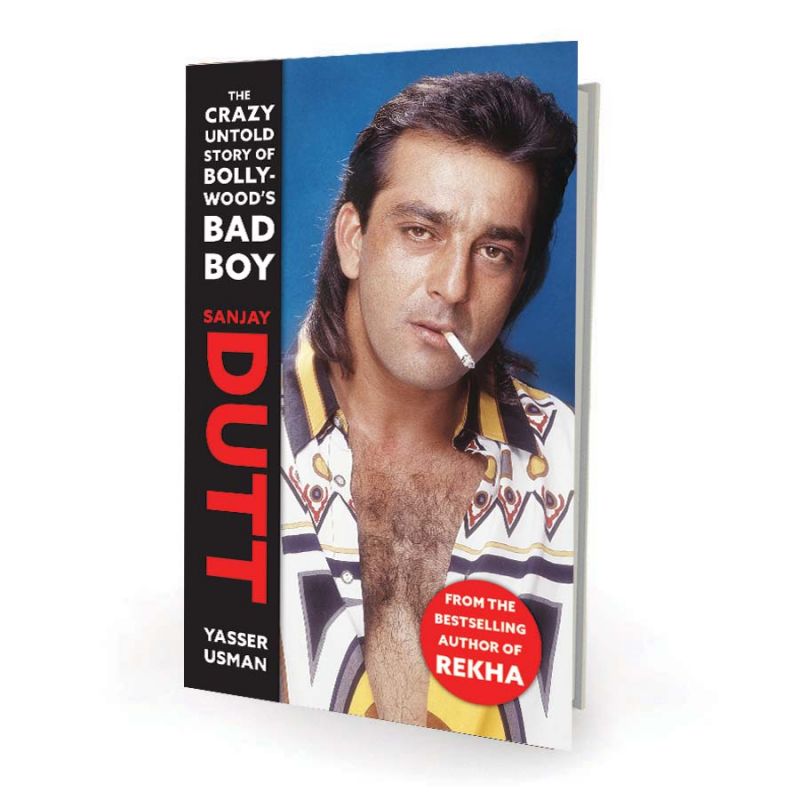

Sanjay Dutt: The Crazy Untold Story of Bollywood’s Bad Boy

Sanjay Dutt: The Crazy Untold Story of Bollywood’s Bad Boy

The decision to write the book, Sanjay Dutt: The Crazy Untold Story of Bollywood’s Bad Boy, was a personal one. In a family passionate about everything Bollywood — my father has been a great admirer of Sunil Dutt — every time the Dutt family passed through a frightening tragedy, it was Sunil Dutt who we empathised with. My book, essentially, is a father-son story and in many ways it is Sunil Dutt who towers over it. He put everything at stake for his incorrigibly errant son. Can you think of another life story that is more epic Bollywood in its reality? My attempt to document this story — the good, the bad and, at times, the disastrously absurd — is a journalistic one, complete with the conflicts, the mistakes, the many heart-breaking tragedies, and the overwhelming triumphs. It is the story of a family of film stars that is sometimes difficult to comprehend with such moments of insanity that are often stranger than any fiction. This is a spectacular story.

In a career spanning almost four decades and more than 100 films, Sanjay Dutt has only around 10 noteworthy films, a poor average by any standard. Then what did people see in him? Why was he such a big A-list star for years? Why did his fans emulated his macho personality, the rippling muscles, long hair, smoking and drinking? This intense devotion of his fans made me more curious. Also, as a keen observer of Bollywood, I was dismayed at how our perception of Sanjay Dutt shaped post-1993. How it over-defined him. And when I started researching, it was shocking to know that the signs were always there. How many people know, for instance, that almost a decade before the 1993 Mumbai serial blasts case, Sanjay was involved in a shooting spree in the posh Pali Hill area for which he was even arrested?

Sanjay Dutt was perhaps the first offender who made the offence seem cool, legitimised through the lens of Bollywood’s familial loyalties and stardom. And he let this get to his head.

In fact, when he was arrested for his alleged involvement in the 1993 Mumbai serial bomb blasts, the common narrative in the film industry and in a large part of the media was to project him as “foolish”, “stupid” or “naïve”. I strongly debunk this theory with anecdotal evidence. Sanjay told the police he acquired the deadly AK-56 and ammunition for the “safety” of his family from the rioters. In my book, it becomes clear that he already had three licensed arms and one unlicensed gun before he willingly acquired the AK-56 for which he was later incarcerated. Given the facts, how does one challenge Bollywood’s collective, persuasive perception that he was just a naïve fool?

It was easier said than done. This is where unauthorised but journalistic accounts come into play. I have personally always felt that many film books, biographies or memoirs on popular cinema are either “safe” insider versions that make everyone happy, or boring “academic” cinema books. Sometimes, the subjects try to look back at their lives through rose-tinted glasses. The “positive” events are talked about in detail, but uncomfortable facts are wrapped up in a few lines. For an unauthorised biographical account, the research is extremely long and tedious because there is no one-point reference source for all your information.

Very few wanted to talk about Sanjay at all. Some were scared, a few said this will affect his case (which is over) and some said that he is a misunderstood “boy” (of 58 years). It was a difficult and humbling experience chasing people who want to ignore you. I had to bear the suspicions and royal ignore of people from Bollywood. My requests for telephonic interviews or meetings regularly went unanswered. People either hung-up on me or had no time to meet or talk.

There were two instances where I even flew down to Mumbai and Chennai as a star and a filmmaker had promised to talk. They ditched. But, thankfully, over a period of time few crucial ones agreed to speak and gave great interviews. That’s how journalism works. No one can control everyone. In Sanjay Dutt’s book, it was Mahesh Bhatt, Sanjay Dutt’s classmates and teachers from school, co-stars and many police officers who shared their memories and stories of him.

People ask me if not talking to the subject and his family is a handicap. I agree, it would have been so much better had I got an opportunity to interview him at length apart from the ones I have done with him around his films. But then, how do you research and write about history? In the absence of the primary source, you look for the secondary sources for piecing the narrative together. Can you imagine the incredible media coverage that a controversial star of his stature would have commanded?

I went through hundreds of interviews, books and journals — some of them rare and definitive. The foremost challenge was to gain access to such archives and separate the wheat from the chaff. I spoke with his directors, co-stars, technicians and also journalists who interviewed him. I talked to a number of people to weave his filmography subtly into the narrative. The crucial films walk hand-in-hand with details of his personal life — both having affected each other, and being affected by each other. At the end of it, I believe, I have presented a star as a human with many dimensions.

So while Sanjay Dutt can question how can there be an unauthorised account of his life but that is a journalistic right that he cannot, and should not, deny anyone. A public life cannot just be seen through rose tinted glasses and selective amnesia.