Retelling an epic-like struggle in Kerala in a contemporary setting

CHENNAI: “Even now no one knows how many people perished in the Vayalar shootout,” sighs Aparajitha, a research student from Delhi who comes down to Punnapra-Vayalar to get “an accurate account” of the Communists-led October 1946 uprising in those two villages of Kerala.

The young woman researcher was also trying to trace her own roots with her late father hailing from Kerala and mother from Bengal. Aparajitha discusses with her friend Disha, also from Kerala, on how historical researchers have estimated the casualty figure in the Punnapra-Vayalar shootout, ranging from 500 to 7,000!

Disha at that point exclaims she wished she could fly backwards in time as in HG Wells ‘time machine’, an idea with which Aparajitha concurs after hearing the story of comrade Anakahashayan’s role in that great struggle; it later exploded into a ‘rebellion’ by an assorted mass of working class people- fishermen, toddy tappers, agriculture labour, coir factory workers, Dalits and so on-, against the exploitative and highly oppressive regime that Sir C P Ramaswamy Iyer, widely known as CP, as then ‘Diwan’ of erstwhile Travancore state was trying to impose on the people, even toying to introduce the ‘American model’ of executive Presidency in that small princely state, reducing the King to a mere figure-head and allegedly wanting to assume all executive powers unto himself!

“Aparajitha spread her hands like wings. ‘Let me also fly backwards along with Anakhashayan….through him, we shall witness those soul splitting scenes.

Disha sat in the shade of the lone tree on the top of the sand hill. Kochhu Raghavan master was narrating the story of Anakhashayan…Not exactly story, but history, said Kochhu Raghavan master.”

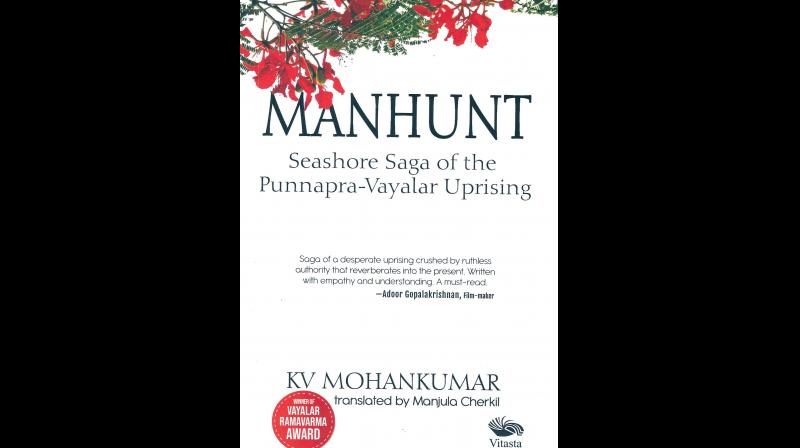

These lines do give a flavour of this masterly epic-like historical novel by one of Kerala’s very distinguished novelist, KV Mohankumar, IAS, whose award-winning novel in Malayalam, ‘Ushnaraashi- Karappurathinte Ithihasam’ has now been translated into English by Manjula Cherkil, as ‘Manhunt: The Seashore Saga of the Punnapra-Vayalar Uprising’. Significantly, this felicitous, gripping English translation comes on the eve of “hundred years of the formation of the Communist Party of India (CPI).”

The massive 609-page novel that seeks to retell the history of a turnaround period in modern Kerala’s economic and social history, from about the late 1930s’ till Sir CP Ramaswamy Iyer “relinquished his powerful position and left Travancore forever” four days after India got her Independence on August 15, 1947, as the author puts it-, in a quasi-fictional mode, sparkles as stories within a story, capturing the pathos and tragedy of the subalterns, of the underprivileged that climaxed into a bloody confrontation of spears and stones against the guns and bullets of the erstwhile Travancore state police and army. The ‘might is right’ dictum of the ruling class of landlords and their associates, is seamlessly juxtaposed with ‘sprouts’ of a class struggle that throws up people with fortitude, empathy and ultimately willing to fight injustice.

Spanning over three generations, this non-linear narrative also throws light on how the Communist movement in Kerala under leaders like A K Gopalan,P K Kunjambu, EMS Namboodripad, to name a few was given shape, aided by scores of comrades trying to take forward the Marxist ideology; countless people killed or jailed during the Punnapra-Vayalar revolt, charged under draconian sections, had to wait for their dawn until the first elected Communist party government in Kerala took office in April 1957, under the helm of EMS, Achyutha Menon and K R Gowri. “Ocean of humanity roared. The cremation ground turned crimson with thousands of red flags fluttering……..The leaders were paying homage to the martyrs (of the Punnapra-Vayalar Uprising) with flowers. After that they went to the memorial of Comrade Krishna Pillai and raised their fists skyward,” the author captures that mood in dramatic words.

However, even as this saga unfolds through the eyes of who may be called the third generation of comrades’ kin - Aparajitha and Disha generation-, Mohankumar’s text bristles with multiple levels of meaning; it is also a throwback, albeit briefly in parts, to the ideological differences within the Left movement in the country, the post-war fallout of B T Ranadive’s ‘armed struggle strategy’ provoking Nehru to declare CPI as “illegal”, the Left parties then changing their strategy, the subsequent emergence of a more radical Maoists movement to contemporary right-wing currents amid globalization; all these and more lend to the larger story a continuity with breaks, and yet affirming a thin hope in keeping alive ideals of Marxism as a universal form of egalitarian humanism to this day.

There is a finale twist to the tale, even if the story is told. The reader is left wondering whether Aparajitha will complete her book on the ‘Punnapra-Vayalar uprising’, for which she digs into various libraries of Malayalam newspaper offices to ascertain factual details of the struggle from the reportage of those days, talks to several old comrades who recount specific aspects of the struggle down little details of which camp was organised where, and who was assigned what when the Communist leaders directed the struggle even if it got crushed later. There are meditations on whether CP should take all the blame, the ‘Maharaja’ or both.

Move on and Aparajitha is having a conversation with Vasudevan Master-himself a mine of information and on the verge of completing his historical novel on the uprising for which he has been collecting, researching material, backed by his own insider’s grasp and writing over the years-, when she receives a shocking information; the laptop on which she had put all her writing for her ‘Saga of the Seashore’ has been seized in a police raid. The cops are probing a suspected Maoist link of her friend Disha’s brother! In the next parting scene so to say, Aparajitha has to leave for Delhi on some urgent work and before boarding her flight, she suggests a title for Vasudevan Master’s book as ‘Scorched Earth’, a lamp for writing her own book!

The author thus ends on a soul-searching note, posing as it were whether the writing is more important than the telling of a complex story or is writing less relevant in the context of action. The descriptions of the violence that people face from police brutality, the poverty in the villages that turned action-points inspired by the Communist ethos, moments of deadly confrontation on the seashore when the sands turned red, ignominy of submission and assaults that women have had to undergo under feudal lords, spread across different chapters, are chilling.

Do words exceed deeds or can words ever capture such deeds, is for the readers to really ponder. But the translator’s style is lucid and compelling that one cannot drop the book. M.A. Baby, CPI(M) Politbureau member, puts the narrative in his studied political perspective: “The author has captured even the most complex historical moments and delicate nuances, portraying them as significant and gracious. The magic with which history is retold is mesmerising.”