Earnestly rendered compilation portrays a flawed genius

The Progressive Writers Union was the undoing of quite a few talents.

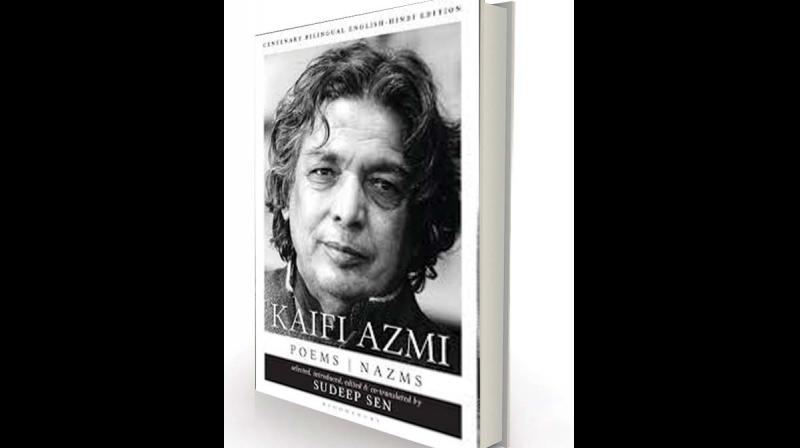

In his centenary year, it is meet to pay tribute to Kaifi Azmi, poet, lyricist, activist, member of the Communist Party and a fine self-professed secularist. In 1959 I saw the film Kaagaz ke Phool at least twice for the Waheeda Rehman scene where the song, sung by Geeta Dutt, written by Kaifi Azmi — waqt ne kiya kya haseen sitam — is played. It is poorly translated by Sumantra Ghosal in this volume. Simple lines like “Tum bhi kho gaye, hum bhi kho gaye/Ek rah par, chalke do kadam” have been rendered in translation as “Treacherous the path, quick to betray/You lost your way, I lost my way!” Where is there any mention of treachery or betrayal in the poet’s lines? The translation goes against the grain of the film. Things unravel in the movie because of circumstance, because of the manner in which life and fortune turn, not due to treachery or betrayal.

The volume contains a fine section on archival photographs. A short introduction tells us Kaifi Azmi, obviously hailing from Azamgarh, belonged to a land-owning family, quit Urdu and Persian studies to join the Quit India movement of 1942, joined the Communist Party and became a card-carrying member. He was a member of the Progressive Writers’ Movement. He went to Bombay and joined Ali Sardar Jafri and wrote for Qaumi Jang. Later of course he turned lyricist and made a name for himself.

Each translator has a section of poems which he has translated — Husain Mir Ali, Baidar Bakht, Sumantra Ghosal, Pritish Nandy and Sudeep Sen. There are two aspects to Kaifi Azmi the poet. There is the political-cum-mushaira poet, who is run-of-the-mill and pretty predictable. But the public was wahwahing this kind of poetry, just as they did the Balakote episode of recent memory.

This kind of syndrome generates a poem like ‘Ibn Maryam’, ‘Son of Mary’.

It starts with “Are you God/Or son of God?” Then starts the lambasting: of smugglers of bhang, ganja and liquor; an attack on machines, (he was leftist after all) a de rigueur line or two on Vietnam, and then the coup-de-grace, “Jesus, you need to mount the cross again”.

One should not be too harsh. A poet, or artist is a creature of his or her times, and slave to prevailing trends. Those were the days you picked up big and obvious subjects. Sahir Ludhianvi wrote on Taj Mahal.

I come from Sahir’s college incidentally. (He was expelled for falling in love with a Sikh girl). Kaifi Azmi also has a poem on the Taj and talks of inequality, has the same sentiment running through his piece as Sahir’s poem has.

The Progressive Writers Union was the undoing of quite a few talents. The authors had an agenda — a leftist one, which is better than the rightist one these days, but an agenda still. Poetry cannot be placed in a hamper — attack capitalists, zamindars and owners of industrial units. These writers were do-gooders. Now doing good may be good for Quakers, but not necessarily for poetry. In a poem ‘Somnath’, Kaifi blunders similarly. What can you write on Somnath? I too am an idol-worshipper, he says.

A poem brimming with righteousness falls flat. He has a poem on unemployment (‘Bekari’), equally flat. There is a poem on ‘Womankind’ — has to be a disaster. Write on a flesh-and-blood woman, not the feminine in abstract.

When Kaifi brings satire to the table, the poems light up. ‘Doosra Banwas’, the ‘Second Exile’, starts on December 6. Ram has hardly washed his feet in the river Saryu when he notices the goons in his house. No point going on, read the poem, as Ram leaves Ayodhya.

This kind of a poem should be in school anthologies, but people like Dina Nath Batra, who had Wendy Doniger’s The Hindus banned, ruled the roost with a certain HRD minister.

Some poems stand out in translation. For instance, Baidar Bakht has translated ‘Wasiyat’ (‘My Will’) or Sumantra Ghosal’s rendering of ‘Dayira’. Sudeep Sen uses two words, when one would do.

For instance, in the poem ‘Two Nights’, the first two lines run as follows: “Jumbled-confused emotions, ask not about them/Scared-frightened favours, ask not for them.”

A single word, “jumbled”, and in the second line, “scared”, would have sufficed and the inversions grate on the ear — “ask not”. These don’t read like lines from a poem.

Pritish Nandy’s renderings sound good in the target language, but both he and Sen don’t know a lot of Urdu. Nandy also takes liberties and skips over lines. In the well-known poem, ‘Anarchy’, an excellent line like “dimag pichle zamane ki yadgaar sa hai” finds no mention in the translation.

It is in his personal poems, love poems, that the music comes out and the poet Kaifi stands out. Most of these poems in this volume have been translated by Sudeep Sen, the best translations in the book. Poems like ‘Tabasum’, ‘Hosla’, ‘Do Rathen’, ‘Doosra Toofan’ (Second Storm) are fine poems. The poem, ‘Mashviren’ (‘Advice’), is rendered excellently by Sen.

But the publisher or Sudeep himself need to be circumspect with the usual eulogistic description of Sudeep Sen as “widely recognised as a major new generation voice in world literature”. In a poetry volume by Sen, this kind of a blurb may pass (though some fellow writers may smile) but this has no place in a book on Kaifi Azmi on his centenary celebration.

The writer won the Commonwealth Poetry Award for Asia