Book review: New ways of looking at old texts, a charm and a sting

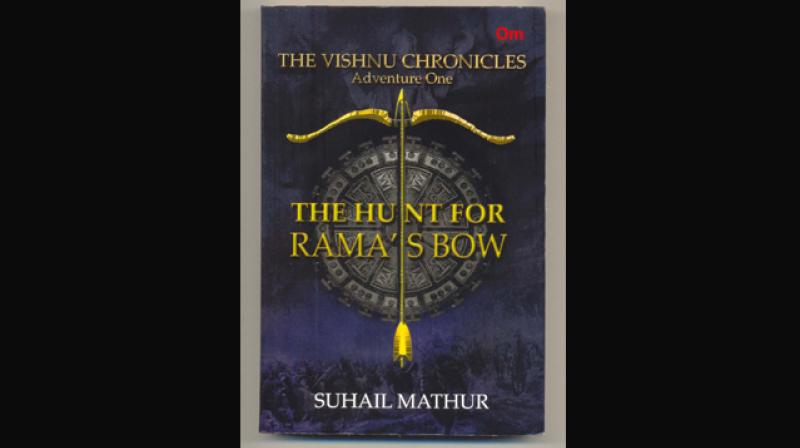

Author Suhail Mathur's latest book offering, The Hunt for Rama's Bow' fiction that is laced with history, Hindu mythology.

Try consciously distinguishing a ‘boat’ from a ‘ship’. Semiotic theorists like De Saussure and C.S. Peirce who contributed immensely to the field of ‘study of signs and what they signifiy’ would tell us, the very utterance of these words – ‘boat’ and ‘ship’- evoke different images and what they stand for. The ‘boat’ is a ‘small float’, while the ‘ship’ is a ‘vessel’ of much bigger size and significance. Going further, Semiotic theorists would say, an entire ‘text’ can be seen as a ‘semiotic system’.

Author Suhail Mathur’s latest book offering, ‘The Hunt for Rama’s Bow’ – fiction that is laced with history, Hindu mythology and set in the backdrop of contemporary events-, seeks to re-articulate the relevance of one of our oldest epics, ‘Ramayana’, through the adventures of its superhero-cum-protagonist, Mohan Sharma, a New Delhi-based graduate.

Energetic Sharma, keenly interested in history and archaeology with a profound Hindu touch, and ably supported by his local guardian and an eminent archaeologist Dr Sujit Chandra and his team of archaeologists and historian friends, could have happily got married to his girlfriend in Delhi University, the vivacious Ms. Samaira Tandon, who has a thousand admirers on campus and who also happens to be a central minister’s daughter.

But before all that they-lived-happily-ever-after scenario unfolds, a strange ‘paranormal’ voice from an eerie past, through a communication on a piece of paper that keeps latching on to Mohan’s house window, pulls him to the village of Sahastapur, in modern Uttar Pradesh, “believed to be part of the legendary city of Ayodhya, Lord Rama’s birthplace.” “It was severed from the holy city when the vast and swift flowing river Sarayu, changed its course after the village was cursed by a sage,” so says the author.

And once at Sahastapur, when Mohan meets an incredibly concerned old man who claims to be his grandfather- Ekashringa by name – his namesake being the Sage who married King Dasaratha’s little known daughter, Shanta, in the epic ‘Ramayana’-, Mohan realizes that the calling of his present ‘janma’ is to undertake a long odyssey, to redeem the village of its possibly ‘Treta yuga’ curse, by journeying backwards in time, so to say.

The narrative moves at different levels- semiotics again seems to be at work here - in that it is both fictional and real at the same time, traversing radically different time orders, from a linear to a cyclical motion, with the sole help of the once-mighty Hindu King Shivaji’s sword ‘Bhavani’, to reclaim the meaning and legacy of the ‘Ramayana’. Mohan moves through forests and valleys, virtually overlapping the geography of the Epic, has to deal with several demonic forces, until Dasavanakoka, the evil force on the other side of the Palk Straits (allegorical for the former Lankan king Ravanna) is “vanquished” for good. That is what makes Mohan’s mighty journey, ‘The Hunt for Rama’s bow’.

All this happens when, in another corner of this earth, Mohan’s archaeology friends, as part of a Central Government-appointed Committee, are busy cracking at Rameswaram, whether the ‘Ram Sethu’, the bridge that Lord Rama’s monkey’s army is believed to have build to take Ram, Lakshman and others to Sri Lanka to defeat the evil force Ravanna and redeem Sita, was indeed man-made or just a natural formation. This question had to be fairly, squarely and authoritatively decided upon, even in the novel, before the Government could go ahead with the ‘Sethu Samurdam Ship Channel Project’!

How the two worlds finally connect in a climax, to help redeem the meaning and significance of the ‘Ramayana’ as an extraordinary text informing modern predicaments as well by solving the ‘Ram Sethu’ puzzle, and by implication re-directing people’s faith in the great epic itself, forms the rest of this novel. The narrative is never dull, as it races through slices of Hindu mythology, history and archaeology. However, is all this possible in the age of the mighty Republicans and post-Truth, one might be tempted to ask.

But the author, speaking through his chief character in the novel, would retort thus: “Mohan blurted out, admonishing his uncle (Dr Chandra) for finding logic in a tale where people are possessed with supernatural powers.” For the author, the likes of Mohan Sharma, seem part of a ‘yagna’ of revisiting and re-articulating the ‘Vishnu Chronicles’ in the context of the new millennium, to try and find new meanings and re-authenticate old role-models of ostensible moral power that people hanker for amid techno miracles of ‘selfies’ and ‘WhatsApp’. That’s why one began this review with a note on ‘semiotics’.

Multi-level fusion literature of this genre comes with a sociological price though. Even until say 50 years ago, epics like the ‘Ramayana’ or ‘Mahabarata’, or tales from various ‘Puranas’ were better heard and learnt by children through a quasi-oral tradition, on grandma’s warm laps. Its freshness and richness was of a different order altogether.

For many others, who stepped into the portals of modern education, it was unadorned texts like Rajaji’s re-telling of the two great epics, supplemented by a sundal-filled evening discourse of a Sreedhar Thathachar or a Kripananda Variyar that reassured people of the values of mainstream religious traditions in India. But in the age of 24/7 television and the Internet all that is largely gone. Texts now come in various formats and colours. The ennobling value of a ‘religious view of life’ amid human infirmities, as Dr Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan would say, should hopefully not be lost in the clutter!