Step away from Outragestan

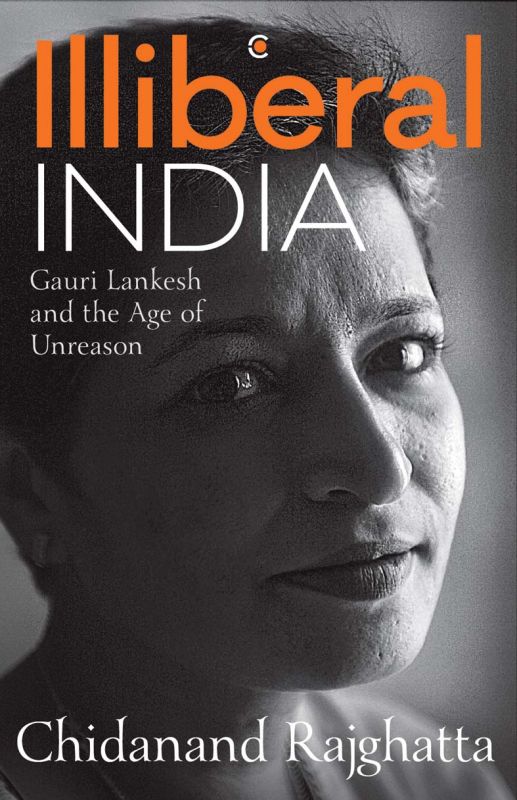

With the recent arrests in the Gauri Lankesh murder case, we interviewed her ex-husband.

This was a friendship that evolved after a marriage turned sour against the backdrop of India's changing political climate... Excerpts from the interview.

Excerpt: She was not just a self-appointed Godmother to her friends’ kids but even your own. She went on to adopt four student activists... Just curious that someone with strong nurturing instincts didn’t want to have a child of her own?

All I can say is we were very young and self-absorbed. We did talk about it, but we were married for only five years, and part of that time was spent apart in different cities as we navigated our careers, which seemed all-important at that time. Much later, she spoke of adopting, but eventually her sister Kavitha had a daughter, and she became Gauri’s daughter too, calling her “avva.”

Excerpt: Our rather bohemian lifestyle and lack of discipline and self control — mainly on my part — had its adverse fallout. Before long, our marriage was fraying... Considering that the two of you shared such a strong bond post divorce, it is unclear as to what exactly went wrong. Clash of egos?

Primarily, one of us had to step back (not give up, just step back) in our careers, and typical of the patriarchal, misogynist times and society we lived in, it alas had to be her. It made her resentful. When we first moved to Delhi, it was because I was making a career move and she had to “tag along” (her words) and when we moved back to Bengaluru, it was again because of me, and when I asked to move again to Delhi, she said adios. At this time I was a hopelessly misguided careerist, and an awful, insensitive male chauvinist to boot.

Shunya: A Novel Context Westland pp. 224, Rs 499.

Shunya: A Novel Context Westland pp. 224, Rs 499.

It’s been about 10 months since Gauri was shot dead. Was writing this book a cathartic experience?

A: I did relive some of our growing up years but I would not say it was cathartic. It is not so much a personal memoir, much less a biography, as it is a social and political commentary from someone who is now witnessing from 10,000 miles away India muddling along. So, I’ve tried to be dispassionate and unsentimental for the most part, just trying to understand and talk about what is happening in India today.

She was the force behind the Karnataka Communal Harmony Forum and had foreseen communal disharmony in the state for years. Did she ever share moments of fear with her loved ones. What happens to this forum now?

She certainly did not share any such thoughts with me and I don’t think she did with her family either. She was a tough kid, a tough woman, quite fearless. She had been attacked viciously on social media and heckled in meetings etc., but I don’t believe she thought she would be the victim of physical violence, and certainly not assassination. In that sense, those who killed her are cowards. I’m sure the forum will continue its work. The good thing about Karnataka, and about India as a whole, is that there are many more people who believe in social and communal harmony and in secularism than those who have a narrow, divisive vision.

One constant factor that arose in conversations post her death was, why wasn’t she given adequate security. She lived alone and refused to hire bodyguards…

Like I said, I don’t think she or anyone anticipated or expected such violence to be inflicted on her, least of all political violence. Her home is fairly modest — not large or ostentatious. I hadn’t visited her at home for the last 15 years, but it was fairly desolate at that time (early 2000s) I did, and I had spoken to her about safety issues around the year 2000. She had a dog those days, and she told me beat constables stopped by her house at night to sign in. I’d think since then, the area got more built-up and busy. But the point is crazed people can kill anywhere, anytime. I don’t know if security is a sufficient deterrent to extremism.

We were young and passionate liberals and freedom of expression meant the world to us... ironically it is this very freedom that cost her her life.

Do you think, in her overwhelming quest to take on right wing extremists, she had become somewhat careless about her own life?

We can say that in hindsight I guess. But again, she did not anticipate such physical political violence. She tangled with a lot of adversaries in social media and even in debates and arguments. But I don’t think she anticipated a lily-livered coward shooting at her.

Manini Chatterjee’s moving tribute talks about the contradiction in her personality Do you think she felt the constant pressure of not just fitting into her father’s formidable shoes, but finding ways to keep the paper running?

Yes, without doubt. In my book, I’ve traced how she gravitated back to her father’s literary and journalistic eco-system after being an English language journalist who was totally disconnected from her roots and her language. It was a difficult transition because, as you say, her dad’s reputation and output was formidable — not just in journalism but also as a poet, playwright, filmmaker and as a literary figure. He was a gifted, felicitous writer who had also honed his craft for decades, and he started the original Lankesh Patrike at a particularly receptive moment for the media — in the 1980s, when there was not much private television and no social media. She had to compete with all this, plus changing tastes of readers, the decline of magazine readership, and at the same time, be economically viable without taking advertising. It was a tough act, a very tough act, but she was admirable in her resolve to keep it going.

How satisfied are you with the investigations post her death?

The Indian police are not given sufficient credit for the kind of work they do and the results they get with their limited resources and manpower. We only hear of the screw-ups. I think the SIT has done tremendously and they will eventually crack the case; I suspect they already have, and they are only trying to tie up loose ends. The failure in India often is of the legal, prosecutorial and judicial process. It is sloppy and takes too long and very often criminals get away with delay and obfuscation. I hope this case is brought to trial and conviction quickly, not just to obtain justice for Gauri (she would not have cared much for herself) but to highlight the dangerous and slippery slope of illiberalism that India is on, something she worried about a lot.

You have managed to weave in the most recent political happenings in the state. Was this a book in progress till it went to print?

Gauri died early September and I began putting down some thoughts in October and November. I wrapped it up in March. Let’s say six months start to finish. But the story of illiberal India is an unfinished story; the final chapter will be written only when we have reclaimed our country, and make it a kinder, gentler one, not the angry and boiling vat of outrage that it is becoming.

Her last letter to you... thanks for having been a part of my life... did she have some kind of a premonition about her death?

I don’t think so. But we spoke a lot about old age and death in the last few years mainly on account of the illness and suffering and death of her father, and more recently, my mother. We hated the suffering and spoke often of how death should be a quick and painless.

Now that it is out in the public domain, how prepared are you for the brickbats and bouquets?

I’ve been a journalist for 36 years, so b & b is par for course. It’s bed and breakfast. The more important thing is if I’ve convinced even a few hotheads to head away from Outragestan to a kinder, gentler territory, I’d consider it a worthwhile effort, one Gauri Lankesh would have been happy with.