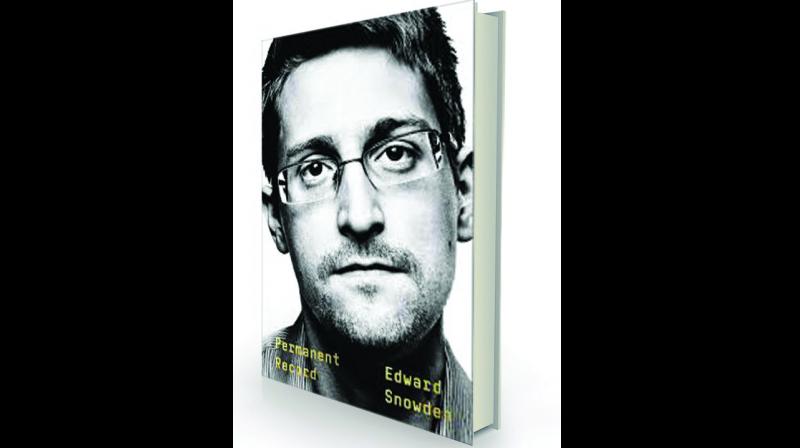

Is Big Brother watching us? Alarm bells go ding-dong in Snowden retold by Snowden

Penning the memoirs of a life retold several times over must have been a challenge.

Being Edward Snowden and telling your story isn’t easy. For a start, what more is there to add to the reams of newsprint, a Hollywood film and countless books already devoted to dissecting his adult life as America’s most written about and documented whistle-blower? Indeed, the Snowden the world knows so well is the systems engineer and overnight hero who risked his life in June 2013 to expose the US intelligence establishment and its illegal mass surveillance programme. It was a revelation that not only shook the world but also brought into focus privacy concerns in the internet age.

Penning the memoirs of a life retold several times over must have been a challenge. To bring freshness to the narrative, Snowden devotes one half of Permanent Record to his under-exposed early years in North Carolina, his patriotic family who served in the government, his obsession with the internet, computer games and the teenage ambition of becoming a super model. It is, if you like, a portrait of a whistle-blower as a young man minus any Joycean flourishes or literary pretensions.

To his credit, Snowden, through very accessible prose effectively chronicles his childhood and the rise and fall of his faith in the internet. Initially, as a teenager, he saw it as a magical medium that would liberate, unite and create a new world order without boundaries. But soon this fascination turns to disillusionment: “To grow up is to realize the extent to which your existence has been governed by a system of rules, vague guidelines, and increasingly unsupportable norms that have been imposed on you without your consent,” he writes.

This disenchantment became that much more pronounced after he began working for the CIA and later as a contractor for infotech corporations which serviced the National Security Agency (NSA) that coordinated invasive and unwarranted mass surveillance after 9/11.

The real juice in Snowden’s memoirs relates to the six years he served in the Intelligence Community. The corroding of the young system engineer's faith in the US surveillance system and the suspect intentions of the CIA and the NSA dominates this part of the narrative and culminates in Snowden fleeing the United States in 2013 with evidence of mass surveillance and handing it over to journalists in Hong Kong. He has been in exile ever since and currently lives in Moscow. This is the stuff that thriller novels are made of.

What value-adds to Snowden’s story is that it is interspersed with explanatory passages detailing the dangers of mass surveillance in the age of internet and smartphones. While most of us can comprehend how big businesses can monetise personal information to target us with preferred products and services, we are not equally clear about how the state can misuse information sourced through phone records, emails, internet activity or medical information. In fact, one widely held myopic notion is that privacy is a concern only for those who have something to hide.

But Snowden argues that privacy is sacrosanct and cannot be compromised in any democracy. To quote: “Ultimately saying that you don't care about privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different to saying you don't care about freedom of speech because you have nothing to say. Or that you don’t care about the freedom of the press because you don't like to read. Or that you don’t care about freedom of religion because you don't believe in God. Or that you don't care about the freedom to peaceably assemble because you’re a lazy, anti-social agoraphobe."

He even imagines a scenario when armed with stored personal data a government could “select a person or a group to scapegoat” and go searching for evidence of a suitable crime. In its effort any “proof” would suffice-old deleted emails, a casual remark made on the social media or associations from the past. At a time when any device connected to the net and equipped with a camera and microphone-be it a smartphone or a laptop-can be made to pick up conversations in your personal space and transmit visuals, creating evidence is easily said and done.

Snowden’s revelations included a classified government document that authorised the NSA to carry out “bulk collection” instead of “targeted collection” of communication data. The agency’s mission was also transformed from “using technology to defend America” to using it to also tap the “private internet technology communications” of citizens which was redefined as “potential signals intelligence”. This paved the way for mass surveillance.

The startling disclosure triggered a “national conversation” in America about privacy. The US Congress launched multiple investigations into NSA’s abuses. The agency and the government, which had so far denied any mass surveillance, were finally forced to acknowledge it. Internationally, debates were revived about surveillance and privacy was discussed across liberal democracies as the fundamental right of every citizen. Businesses worldwide altered their websites replacing http (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) with the encrypted https which helps prevent third party interception of Web traffic. Apple was quick to secure its iPhones and iPads while Google made its Android products and Chromebooks less vulnerable.

Snowden fired the first shot. But the mass surveillance machine is still very much operational and will return to haunt us. At least, Permanent Record seems to suggest that. We simply cannot afford to let our guard down.

The writer is a senior Delhi-based journalist and author