Atwood’s fresh take on patriarchy examines women’s dilemmas

Thirty-four years after its publication, the world of The Handmaid’s Tale does not yet exist, but perhaps it feels even closer than in 1985.

And so I step up, into the darkness within; or else, the light.” It is with these ambiguous words that Margaret Atwood ends The Handmaid’s Tale, a novel that has remained a cult classic ever since its publication in 1985. The Handmaid’s Tale describes a near-future dystopia, where the United States government has been overthrown by a Christian-fundamentalist theocracy. Its replacement, the militarised and insular Republic of Gilead, enslaves and subordinates women, treating them as nothing more than domestic servants, caregivers, or fertility machines. The Handmaid's Tale follows the story of Offred, one of the women tasked with birthing children for Gilead’s ruling class. It ends with her salvation — or betrayal — we are not told which.

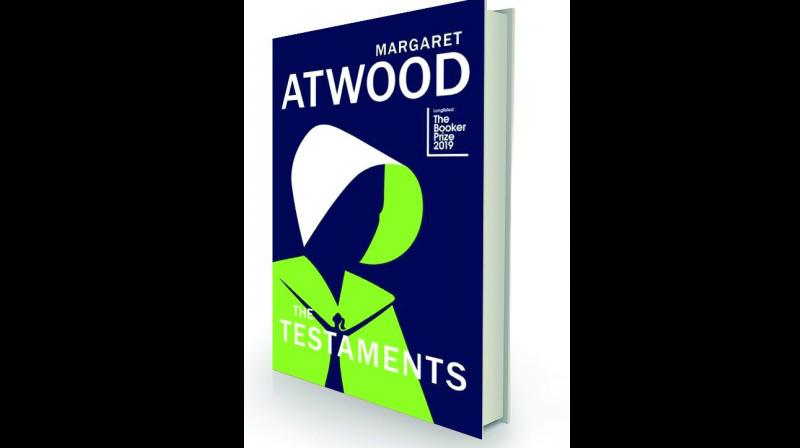

Thirty-four years after its publication, the world of The Handmaid’s Tale does not yet exist, but perhaps it feels even closer than in 1985. Principles of gender equality that formed the cornerstone of liberal democracies — that were treated as settled all these years — have been thrown into doubt. Whether it is the erosion of abortion rights in the United States, the attacks upon “gender ideology” by extremist leaders in Brazil and Hungary, or the backlash against #MeToo, the hard-won gains of decades past appear increasingly under threat. There could be no better time then, for the publication of The Testaments, the sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale — a sequel long promised by its tantalising ending.

If The Handmaid’s Tale was about how an ordinary individual negotiates, resists, and adapts to a brutally oppressive society, The Testaments takes us into the inner workings of that society. Much of the sequel's action takes place in Ardua Hall, the seat of power of “the Aunts” — four women who assist Gilead's (male) rulers to keep and maintain order in the Republic. We are provided the back-story of how, at the time of Gilead’s violent creation, these women were bribed or coerced into assuming; but we are now told that their leader, Aunt Lydia (one of The Testaments’ three narrators), has been biding her time all this while, intent on Gilead's overthrow. To accomplish this, however, Aunt Lydia needs help: help that arrives in the form of Offred’s two daughters (Offred herself remains offstage for most of the novel, although we learn early on that she did manage to escape across the border and into Canada — into “the light”.) One of them, Agnes, has grown up in Gilead, and is on the verge of being given over to Commander Judd, one of Gilead's most powerful men, before Aunt Lydia adroitly brings her to Ardua Hall; the other, Daisy - who is known throughout Gilead as the “missing baby Nicole”, a diplomatic prize — was born in Canada, placed in the care of activist foster-parents, and grows up learning about Gilead’s human rights abuses. Having succeeded, against the odds, in bringing them all together in Ardua Hall, Aunt Lydia must now risk everything on one final plan —that will either bring down Gilead, or destroy them all.

The Testaments picks up where The Handmaid’s Tale left off: we encounter once more Gilead’s brutal and callous ruling class (“the Commanders”), its terrifying law enforcement officials (“the Eyes”), and its hierarchical social structures (with the division of women into Aunts, wives, handmaids, and the “Marthas” and the “Econowives” (domestic labourers)). In addition, we encounter the “Pearl Girls”, who advance Gilead’s foreign policy by traveling to other countries to proselytise for it. The Testaments fills in and fills up the world of Gilead, the history of how it came into being with such suddenness and brutality, and the structures that keep it going: laying bare the mechanics of how easily such a world could come to be.

But while The Handmaid’s Tale focused upon the impact of totalitarianism upon the individual — and how the individual acts when all avenues of resistance or challenge are closed to her — The Testaments is concerned more with the gears and sprockets that keep totalitarianism running — and what it might take to spike them. The centrality of Ardua Hall is a powerful reminder that no authoritarian system can survive without soliciting collaboration from sections of the very class that it aims to subjugate and enslave. It is also a reminder that there will frequently be enough individuals willing to collaborate, through fear, opportunism, or even through a genuine belief in their own inferiority. At the same time, though, it raises the question: is collaboration with an authoritarian regime justifiable if it is done in order to gain access to the levers of power that may some day allow you to challenge it? Is it preferable to an open resistance that only ends in annihilation? And is hindsight the only way to judge between these two paths?

These questions are left unanswered; but most importantly, The Testaments reminds us that every Empire has an expiry date, no matter how invincible or permanent it may seem; and that individual human actions can — and do —advance that date to a time that is closer than anyone would have thought possible. And the more futile resistance feels, the more urgent it is.

The writer is an editor and reviewer of science fiction. His first novel is due to be

published soon