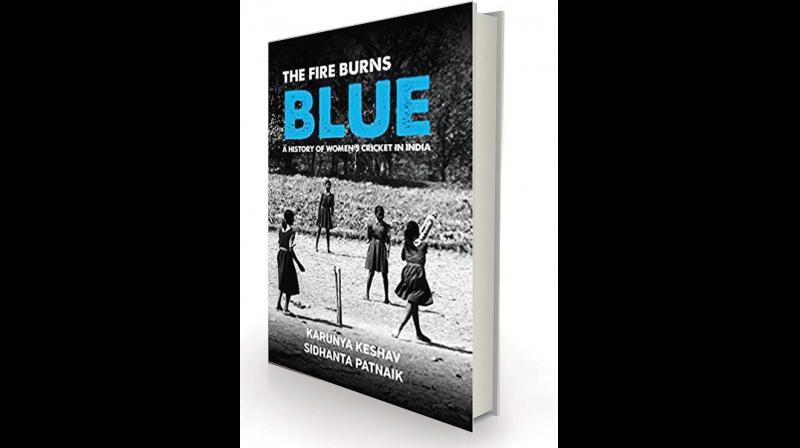

The rise and rise of the women in blue

This is in stark contrast to the long decades when women cricketers struggled for recognition.

For future generations, India’s runner-up finish, by a narrow margin in the 2017 women’s World Cup in England and the bravado in ousting favourites Australia in the semi-final will be seen as the turning point for the women’s game. Since then interest in women’s cricket has spiked and the girls are also getting more recognition, financial deals and even sponsorship.

This is in stark contrast to the long decades when women cricketers struggled for recognition. The Indian women’s cricket team played their first official Test against the West Indies in 1976 and in nine World Cup (limited over) tournaments, from January 1978 to June-July 2017. They missed the 1988 Women’s World Cup. For most cricket fans, however, details of the 41-year-old journey, 1976-2017, remain unclear. Only a few persons like Shanta Rangaswamy (India’s first captain), Mithali Raj (India’s longest serving player who has played for two decades since 1999 and most successful batter), Anjum Chopra (elegant left-handed batter and renowned commentator), Neetu David (skilful left-arm spinner), Diana Eduljee (gutsy all rounder and administrator), Shubhangi Kulkarni (crafty leg-spinner and right-hand batter) and Jhulan Goswami (the evergreen pacer, once the fastest in the world) were talked about. Documentation was scarce.

This void has now been filled by this excellent work. What was till date mostly oral history has been developed through meticulous research and probing interviews into a connoisseur’s delight. The free-flowing narrative makes for easy reading as it is often the versions of the main protagonists — the players and administrators — many of whose stories have been recorded for perhaps the first time— that get an airing. There is fun and frolic like borrowed bats and dormitory pranks but the authors don’t shy away from the more difficult issues, such as how to deal with one’s period if it starts in the middle of a vital match.

Creditably, the book is not just documentation of matches, statistics and players but also provides many sociological insights. It traces the growth of the women’s game from the 1970s to the era of liberalisation, the coming of satellite TV and the 21st century. There is an emphasis on the hidden histories of women’s cricket, the personalities, anecdotes, stories behind the scene, and facts.

The authors deserve credit for providing little nuggets of information, like how the young Arundhati Ghosh, who played 19 internationals between 1983 and 1986, became a cricketer so she could meet Indira Gandhi, the woman she was fascinated by. The book also reveals how Mrs. Gandhi was behind the first telecast of a women’s Test match in India. At the 1984 Delhi Test match vs Australia, the skipper, Shanta Rangaswamy, complained to the then Prime Minister that only highlights of their matches were shown on TV. Mrs. Gandhi beckoned a bureaucrat and instructed him to get the next Test match in Mumbai telecast live. We are also told that current batting star Harmanpreet Kaur’s jersey number till 2016 was 84, a tribute to the victims of the 1984 riots.

The book traces the pioneers of the game in India. Shireen Kiash, the gutsy Parsi girl from Kolkata, represented India in three sports, basketball, hockey and cricket, in the 1970s. Shireen was ambidextrous and could throw and catch with both her left and right hands. After marriage the family migrated to Australia and she died of cancer in 2006.

The authors also focus on the people who laid the foundation for women’s cricket in India. Their stories are fascinating: Aloo Bamji, the Parsi widow from South Bombay who started a cricket club the Albees for girls in Mumbai and gave the players Cadbury chocolates after each practice session, Neeta Telang and Nutan (Sunil Gavaskar’s sister) who founded the Indian Gymkhana cricket team in Mumbai, Mahendra Kumar Sharma, from Uttar Pradesh, who set up the Women’s Cricket Association of India (WCAI), registered it under the Societies Act of Lucknow and held the first women’s national cricket championship in Pune in 1973.

Sex bias and the societally-imposed dilemma of career versus chores, which has affected so many women cricketers, are also spotlighted. Using government data the authors have shown that the median age of marriage for women as per the 2011 census is 21.2 years. In a series of interviews, Keshav and Patnaik have shown that due to social stigma (“you will get tanned and nobody will marry you”) many women had to choose between marriage and a sports career. For some the support systems were either understanding husbands or parents but many remained single. The book records many instances of renowned women cricketers who got married and separated within three to five years, fed up of the “politics in the house”.

Individual cases are examined. The story of Punam Rawat, member of India’s World Cup runners-up squad of 2017, who scored a century against Australia in the group game, is fascinating. Her father encouraged her to play cricket. She made it to the Indian team and then decided to get married to a fellow cricketer. Middle class expectations after marriage, like household chores, stopped her from training, leading to a decline in form. She was dropped from the team. Punam went back to the nets with renowned coach Chandrakant Pandit. Two years after being dropped and single again, she led the run charts in the domestic circuit and returned to the Indian squad for the 2017 World Cup. She built a house in Bandra with the money she got and along with her parents moved from the chawl in Borivili to a new house in a respectable middle class neighbourhood. In other cases, like Neha Tanwar’s, the husband and in-laws supported the cricketer and let her fulfil her dream, even after giving birth to a son. But Neha had a tou

gh schedule and woke up daily at 4.30am to make breakfast and lunch for the family and get the child ready for school. Then again, the father of Andhra Pradesh’s R. Kalpana, an autorickshaw driver, wanted to marry her off early, as the prospective groom was willing to waive dowry. However, her coach and state association officials helped change his mind and Kalpana now plays for India.

The Fire thus covers all aspects of women’s cricket in India, from the early days of travel in second or third class compartments, matches being cancelled due to poor playing conditions or political unrest, mediocre living conditions, to flying business class to compete in global tournaments, cheered on by a TV audience of millions. The controversies have not been glossed over. In 1995, on India’s tour in New Zealand, then India captain Purnima Raut was slapped by chief coach, the late Sreerupa Bose. The provocation was trivial and Purnima was in tears. Purnima claims that she wanted to stay in a shared room, not the single room she was allotted as captain.

In another shocker, a player was named captain of the side, only to be dropped from the playing XI soon after. Ego problems among administrators led to Mithali and Jhulan Goswami alternating as captains. Rangaswamy, one of the pioneers of women’s cricket, had emerged from the dressing room with a placard reading “Down with Murugesh”, a selector, protesting parochialism in selections. The rebel tours of Europe, the US and the West Indies in 1979 when the Women’s Cricket Association of India (WCAI) struggled to give the national team international exposure are also highlighted.

There were good Samaritans too. Former president of WCAI Anuradha Dutt pitched in to reward the team with a Hong Kong trip after their historic overseas win. Actress Mandira Bedi helped procure sponsorship and Infosys let the national women’s team use their playing facilities. The role of Tej Kaul, coach, trainer and physiotherapist of the National Institute of Sports (NIS), in the 1980s is also lauded. The role of the Railways and Air India in providing employment to women cricketers and exposure in domestic tournaments is written about in great detail.

It took Keshav and Patnaik three years to research this book. Women’s cricket, meanwhile, has come a long way. “We never thought about what we would gain or achieve... We loved the game, we were mentally free... we just played,” says Lopamudra Bhattacharji, a former medium-pacer.

Hats off to the women in blue for helping change Indian society for all Indians. Chak de India!

The author is a sports commentator and writer