Celebrating Jane Austen's world in modern society

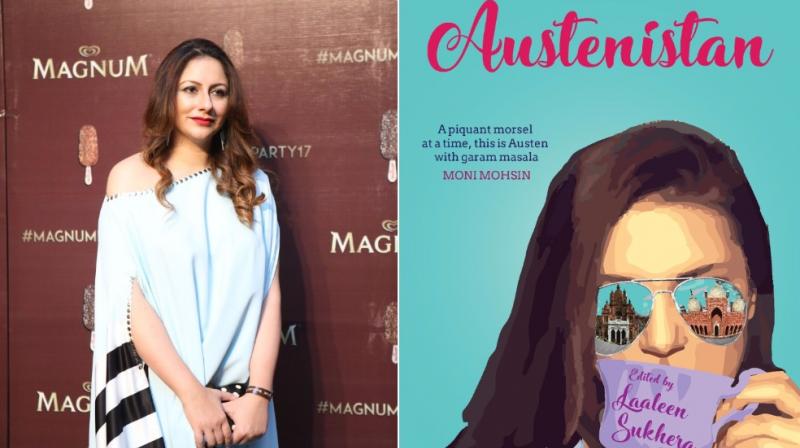

Founder of Jane Austen Society of Pakistan and editor of Austenistan, Laaleen Sukhera talks of weddings, families, second chances in love.

Are the works of Jane Austen relevant even today? Comprising seven stories set in contemporary Pakistan, Austenistan is a clever piece of work amalgamating a range of emotions, from savage sarcasm, to love and second chances in a contemporary society that is still holding on to the last shreds of sense and sensibilities from Regency England.

Edited by Laaleen Sukhera, founder of Jane Austen Society of Pakistan (JASP), the stories penned in the book are written by journalists, editors, lawyers and medical health professionals, and show in various degrees how Austen’s works still hold relevance in the modern society, at least when it comes to love, loss and the marriage market.

Speaking about how the collection came about, Sukhera says the idea was cooked up during the “tail end of a JASP meet up.”

“We toyed with the idea of writing fiction someday and I remember going home and thinking to myself, ‘why not now? What are we all waiting for?”

Shortly thereafter, Sukhera had written the concept down, invited story submissions, and—before the manuscript was even ready, the editor says publishers were competing with offers.

JASP, says Sukhera, is a literary community of like-minded enthusiasts of Austen’s novels and postmodern tributes such as period drama.

“There are about 1,800 online followers from 45 countries, and 90 per cent are women. We have chapters in Islamabad, Karachi, Lahore, and London, where we meet up in small groups of 6 to 12 at cafés and discuss all things Austen to our hearts’ delight,” she says, adding that they also host annual dress-up tea parties where they channel Regency fashion and Austen characters and “unleash” their eccentricities.

The stories compiled in the book, seemingly portray an affluent socio-political Pakistan background and Sukhera says that the writings are works of fiction and people write what they know. However, she begs to differ on the fact that it only highlights one section of the society.

The British-Pakistani writer says that many of the issues experienced by characters in the stories are not limited to a particular social class. She lists these issues as domestic abuse, financial insecurity, adultery, substance abuse, toxic relationships, and the claustrophobic wretchedness of unhappy marriages and closeted homosexuality.

“We’ve actually juxtaposed the upper echelons with middle and upper middle class characters and contexts as well,” she adds.

Speaking about the book itself, Sukhera says that while she wanted Austenistan to be like a wonderful ‘jewellery box’, having to edit stories to bring that effect was difficult.

“Reducing the word count can be a heart breaking process,” she says, adding, “I was fortunate enough to be working with Faiza S Khan of Bloomsbury and I have full faith in her shearing and pruning abilities.”

Going through the pages of the book, one can find a subtle undertone of Austen sensibilities playing through the lives of the characters in each story.

Sukhera puts it down as being the relevance of Austen’s works even in contemporary world.

“In South Asia, we often find ourselves in very Regency-esque situations. Whether it’s a marriage proposal received through one’s family or even a match arranged between cousins, it’s sometimes tricky to distinguish Austen’s era with the twenty first century.”

The book also sees short excerpts before each story that set the undertone or flavour for the same. She elaborates, “The quotes bear relevance to the stories and the main protagonists and their situations. I hope that Austen enthusiasts will enjoy them and that readers unfamiliar with Austen will find them illuminating.”

Ask her about the contrast of modernism and old world values that run throughout Austenistan, Sukhera adds, “It’s second nature for us because we’ve literally grown up in Austenistan with its quixotic mix of convention, misogyny, evolution, and decadence.”

She explains this by saying that contributor Gayathri Warnasuriya is Sri Lankan but she’s spent enough time in Islamabad to get closely acquainted with its society and culture to write about it with aptitude and eloquence. Similarly Sukhera adds that Nida Elley, who lives in Austin, Texas, partly grew up in Lahore too and has given a brilliant and evocative piece of writing to make the collection.

“As they say, you can take the gal out of Pakistan but you can’t really take Pakistan out of the gal!”

As for what the book hopes to convey, Sukhera emphatically points out that it attempts at conveying humour, hope, curiosity, fascination, and “a thirst for more savvy, sassy heroines who happen to be brown skinned and are relatable worldwide rather than exoticised.”

The author who has contributed one short story to the collection herself and believes that there would always be a possibility of another Austenistan (since “One can never truly run out of stories.”) adds on a parting note that drawing room novels -- like the works of Austen, and Austenistan -- would always be a part of mainstream society, even in a postmodern world.

“We might be scrolling Facebook and Instagram and responding to a dozen WhatsApp chats but we’re still doing it from our drawing rooms, for the most part,” Sukhera concludes.