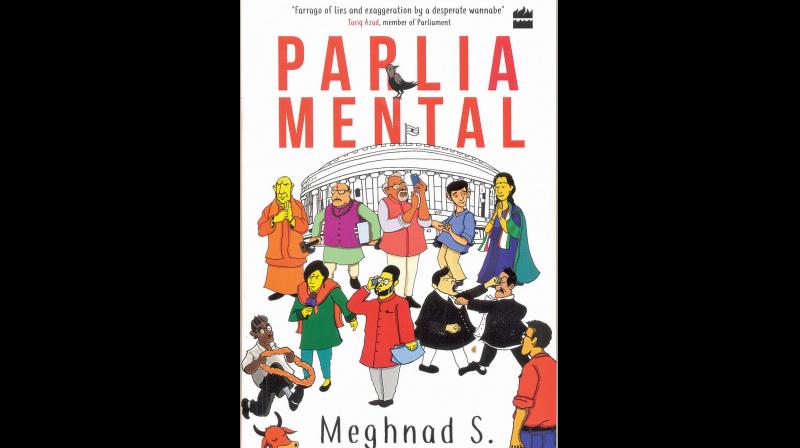

A fluffy take on the seamy side of power play in Parliamentary practice

There is yet a pun in the way the author has stylised the title word, without being unparliamentary of course!

CHENNAI: It is uneasy to guess whether’Parliamentary’has been given short shrift to consciously sound’Parlia Mental’, the title of this fictionalised personal account by S Meghnad, a columnist, public policy professional and podcaster who worked eight years with at least six MPs’before essaying this text.

There is yet a pun in the way the author has stylised the title word, without being unparliamentary of course!’Parlia Mental’can also be seen as a theatre - in our instance a big circular building in Lutyen’s Delhi - where ideas and procedural actions, which are not always laudatory, are in a hotbed of confrontation, tempered by a numerical consensus in shaping the country’s legislative destiny.

But there is much more to making laws by the lawmakers as Meghnad tries to show his readers in this book, without naming the real heroes for obvious reasons. Several layers of personal, political ambitions, party gains and larger avowed public interests have to be decoded, and some of which get fleshed out in the political classes’interface with the media. One gate in Parliament complex is earmarked for the media stand, the new broadcast gateway.

And today the media is more synonymous with its dominant sections of the visual, Internet and social media; thus the protagonist of this thinly veiled memoir, Raghav Marathe from Nagpur - it’s a coincidence that the RSS also has its headquarters there - who moves over to Delhi as secretary and political analyst of the first-time MP of a regional party RJM, Mr. Prabhu Srikar, elected to the Lok Sabha from Nagpur, deftly uses his media contacts as much as the media would like to use him for its scoops! His Twitter handle is his best bet.

Writing speeches for his MP, Raghav realises from close quarters the power of those words going places, particularly if one were to be like the Bollywood actor-turned MP Ranveer Chopra, as in the book, who “had eleven million followers on Twitter, forty million on Instagram and over a hundred fan pages on Facebook.” “There was a cult around him, plain and simple, which was obsessed with everything he did. Raghav imagined him speaking in Parliament and how his cult would react after that,” writes the author with great deal of vigilance. Any similarity to present Parliamentary reality is at best coincidental, he confides.

But when the Government of the day wants to introduce a new bill, the’Social Media Regulation Authority (SMRA) Bill’to control the social media, more so after the online media had torn into the regime’s intentionality of a law on’electoral bonds ‘that gave immunity to political parties from disclosing their’donors’, and going hammer and tongs on a huge scam in a cooperative bank in Maharashtra’s sugar empire, the first-time MP, Prabhu Srikar has a mind of his own. This despite the fact his party RJM wants to support SMRA Bill, and fields Chopra to back it.

But Srikar does not take this lying low. He tells his colleague, “Ranveer, this is not just about abuse. It is also about the government controlling the narrative, don’t you see? If any posts anything that the government is uncomfortable with, they will take action against that person. They will launch an investigation. Even arrest them.”

“Chopra chewed on his lower lip. He quickly took the phone from Raghav and tapped on it.’Look at this. The Prime Minister’s profile; He follows me. Just open any tweet and see how vile people are to him! How can they talk like this against the government? This has to stop!’ “But the Prime Minister is not the government, Sir,’said Raghav, unable to control himself. He looked at Srikar to see him shaking his head gently, signalling him to stop. Chopra looked at Raghav and said, ‘what? What do you mean? We all voted for him! Of course he’s the government’. This was too much to handle for Raghav, writes the author at the end of that passage.

Such is the flavour of this narrative, in easy, informal, conversational style, abusive at times, sardonic, patronising and the mutual admiration club that parliamentary party meetings can turn into, by which the author Meghnad has given his text a touch of radical realism! The story flows from one scene to another, underpinned by the conversation of the context. It is interesting and revealing as he seeks to tell the story as a’Parliamentary insider’of sorts when key legislations are passed and how the chaos in the House generates its own dynamics, at times its own sub-plots!

But when freedom of expression is under threat and fired-up MPs’do their part to fight it with help from the media, the author shows how complex the outcome can be when something is’bulldozed through with impunity’. And if the Bill does not still get the Rajya Sabha’s nod, there is always the Ordinance route! The fighter at one point is so exasperated that he almost gives up and has other fishes to catch, other deals to be made, as the author seeks to show quite candidly.

Raghav Marathe’s own troubled past, the way he knots in with Srikar, who was not expected to win the Nagpur LS seat in the first place, a bank scam, the investigative drive of a young woman journalist who covers politics for a US-based’youth friendly website, The Daily Plug’, and a rising YouTube star, are all weaved into the narrative in a matter-of-fact way. They all come together for a cause only for the cause itself to exceed them! Politics is not just idealism, the author shows.

After all the firings, suspensions, finally when the ‘good to be back’tune is being played out, Raghav finds himself comfortable taking selfies with the Neta-class in front of the’perfect picture’. Guess who? Veer Savarkar. That, through the author’s prism, gives a sense of the political context of the day. So, after all the realism of this novel, it closes on a cynical note. Hard way, perhaps, to know the real!