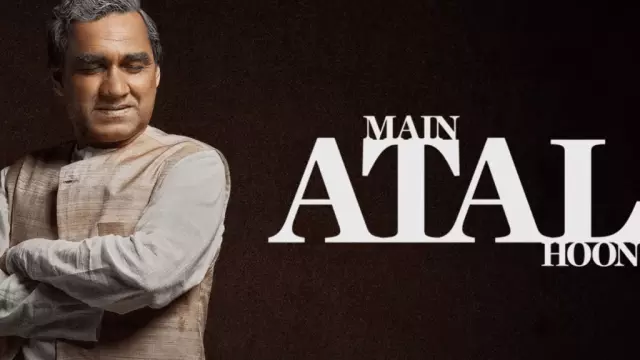

Movie Review | Main Hoon Atal: Factually correct, imaginatively poor

Cast: Pankaj Tripathi, Piyush Mishra, Raja Rameshkumar Sevak, Daya Shankar Pandey, Pramod Pathak, Payal Nair

Directed by Ravi Jadhav

Authenticity in purpose is often the first casualty with biopics in the Indian context. Time it as a planned narrative, and things get worse. Paradoxically (read inadvertently), Atal Behari Vajpayee echoes Nehru more often than he would for a forerunner of the contemporary lotus ideology. There is an eerie hangover from Georgi Gospodinov’s ‘Time Shelter’. To the uninitiated, the latter is a metaphysical work on taking a life back to the past in the present — living in the paradox of contemporary wisdom and inexperience of the past, the cynicism of the present that is coloured by the naïve hope of the past.

Arguably, former prime minister Vajpayee led a colourful life and had a life story that was pregnant with possibilities and opportunities. Juxtapositioned with questionable honesty and denominated by times when the New Historian is on the lurch, the script is intellectually dishonest. Factually just correct, imaginatively poor it turns into yet another florist collective than showing the warts and beauty of India’s tenth prime minister. Atalji’s life is perhaps a thematic reflection of Gospodinov’s words: “The cosmic future also seemed unclear and suspicious to him, the new order, the new people — all of it sounded so distant and hollow. The bright future gives me heartburn, he once told a group of friends…. My objections to the system were not so much political as aesthetic”. Atalji’s life stops in ‘Main Hoon Atal’ with the Kargil story. Strange is it not that a messenger of inclusivity finds the high point in a war. Also, for a biopic, the central character is a tad too enthusiastic and involved in marketing himself.

Tangential references to historic ups and downs are the engineered format of filmmaker Ravi Jadhav. Typically, life starts off in a village school and, a la Winston Churchill, Atalji begins as a defendant speaker. Arguably one of India’s greatest speakers alongside Dr Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Pandit Nehru, who would believe that the butterflies in his stomach would seal his lips! Dad Krishna Behari Vajpayee (Piyush Mishra) inspires Atalji. He even joins law school and shares a hostel pad with his son. The regulars Deendayal Upadhyaya (Daya Shankar Pandey) and M.S. Golwalkar (Prasanna Ketkar) have miniscule roles suggesting peripherally their impact in the making of Atalji as the most accepted (historically) face of the right wing party. The streaks of the government that for political reasons could blur the lines between faith and belief are visible by accident or for lack of sufficient flesh to contribute for nearly 140 minutes. The film records Shyama Prasad Mookerjee (Pramod Pathak) establishing the BJP, seeking albeit in vain a political marriage with the RSS. The prophecy of Atalji and his vision (mission!) to garner and build the “largest party in the history of the country” rings true but for architectural deficiencies thereafter. His tryst with Hastings is lost. His defeats hidden. His victories highlighted. In fact, it would have made for an amazing script to present the humane face of Atalji in the hours of his struggle and failure. Instead, crass pot-shots at Article 370 are taken. The fights with the British stop short of being a carry cager. The man who saw the 3 per cent to 30 per cent growth is in his heaven. Perhaps watching in confusion from the worlds elsewhere at the subsequent growth of his political party if not his political vision. The closure to the Nehruvian era is punctuated by minor interactions between the two giants — Nehru’s hope in Vajpayee and the latter’s respect for the former are defining moments and pleasantly survive the contemporary painstaking narrative. The death of Deendayal Upadhyaya under suspicious circumstances, the camaraderie between Atalji and L.K. Advani (Raja Rameshkumar Sevak) garnered as much space as the death of Lal Bahadur Shastri.

Interestingly, Atalji’s famed bullock cart ride to Parliament protesting fuel prices may see partymen run for cover again. Perhaps today’s diehard partymen do not share Advani’s passion for Bollywood. Another area that could see a changed strategy from the days when the lotus began to bloom to the time when it flourishes is Atalji’s consistent advocacy for inclusivity. The Black Wednesday, the formation of the Janata Party, the famed Nehru portrait episode are known footnotes of history or the scribbles of the well-known times. The poet, the artist, the romanticist, seeks and craves for space. The seeds for kar seva and the road to January 22 are laid. Two interesting Vajpayee statements stand out if they do not mock. One, “only he can remove hatred who loves the nation” and the other, “there is no place for hate in the nation of love”. The Buddha Laughs statement as India entered the nuclear club is intentionally suspect since it does not refer to the first nuclear picnic at Rajasthan under the leadership of Indira Gandhi. The film suggests that even the home minister did not know about it. As the dramatic ambassador of peace with the neighbour, the Lahore bus ride and the turn of events leading to the Kargil victory are obviously highlighted. Interestingly, at India’s inclusion in the nuclear club, Atalji says “Jai Jawan Jai Kisan Jai Vigyan.” Atalji blames the Congress for horse trading — life has come a full circle.

The growth of the lotus party is poetically summarised in a way that only Atalji has: “Dalonke dal dal me ek kamal”.