World moving towards protectionism since crisis, 7,000 measures introduced

A research found that the United States and European Union were each responsible for more than 1,000 of the restrictions.

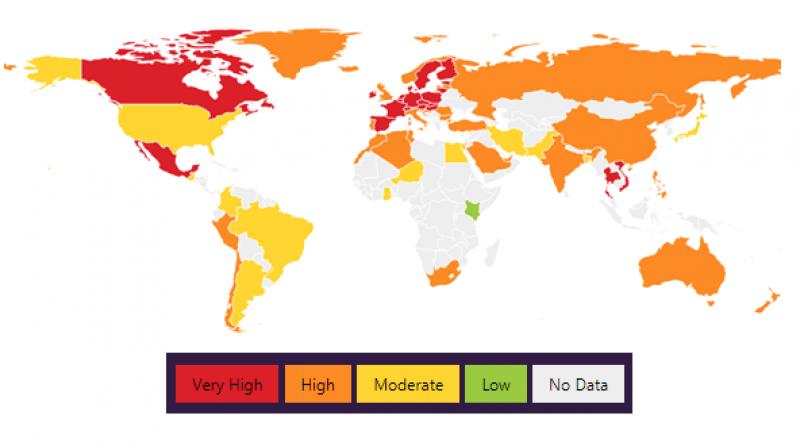

London: The world’s top 60 economies have adopted more than 7,000 protectionist trade measures on a net basis since the financial crisis and tariffs are now worth more than $400 billion, a study of global data showed on Wednesday.

The research, which drew from World Bank, Heritage index and Global Trade Alert figures, also found that the United States and European Union were each responsible for more than 1,000 of the restrictions.

India was next with over 400 followed by Argentina, Russia and Japan all with between 365 and 275, while only three countries - Brazil, Saudi Arabia and Tunisia - had liberalised trade rules on a net basis over the period.

Last year meanwhile saw the highest level of protectionism in percentage terms since 2010, at just over 61 per cent of all the trade measures introduced or modified.

“Donald Trump is getting all the headlines at the moment but everybody’s doing it,” said David Lowe, head of international trade at law firm Gowling WLG, which produced the report.

The study, which mostly looked at the eight years before Trump gained power, did not put a severity weighting on the measures it identified that ranged from automotive tariffs to regulations on more unusual products like pet collars.

Nor did it identify sector trends, but it did show the trade relationships between different countries and who was affecting who the most.

For all but nine of the 60 countries where data were suitable, it was the United States that was having the most impact. Russia and China also scored highly due to Russia’s exports of oil and commodities and China’s worldwide export base.

It also showed who had the most to gain and lose from protectionism potentially. The United States for example has a very low reliance on trade as percentage of its GDP at 28 percent.

That makes it only “moderately susceptible” to protectionist changes, whereas Russia and Germany have much higher trade to GDP ratios of 51 per cent and 86 per cent respectively.

“You can see why Trump is talking so tough about deals like NAFTA,” Lowe said. “Because he can.”

Britain could also be susceptible. Trade, much of which is services in its case, is worth 57 per cent of its GDP which is higher than China’s 41 per cent.

Lowe said Brexit was one of the reasons why his UK-based office compiled the data. Brexit supporters say quitting the EU will give Britain more freedom to trade with countries around the world, but protectionism could make it more difficult.

Striking a new deal with the EU will also be haggling with a bloc that has been increasingly protectionist.

“Leaving the EU is being presented as entering the land of milk and honey. But there is no such thing as free trade anywhere,” Lowe added.

It also carried out a separate survey of the heads of 350 UK companies, the majority of which trade with between 6-20 countries, and 150 general counsels.

Roughly 80 per cent of the total 500 respondents expected protectionism to continue to increase, while just under 80 percent also thought there would be a global recession in the next five years.

The broader survey showed too that trade tariffs imposed around the world totalled $401 billion. Brazil is one of the few countries that has liberalised trade overall but it still pulls in $39 billion from tariffs.

In the United States it is $39 billion, in China it is $62 billion, while in Mexico and Germany the data showed it was around $20 billion.