Talks with Pakistan a weapon, use it wisely

Speaking recently at the Kautilya International Foundation in New Delhi, I said that Chanakya should be mandatory reading for all diplomats. In saying this I was not only paying tribute to the author of the world’s first substantive treatise on statecraft, the Arthashastra, written sometime around 150 CE, a millennium and a half before Machiavelli wrote The Prince in the 16th century CE. I believe that the Arthashastra is essential reading because, even if things have changed greatly by now, the treatise contains essential lessons about the conduct of diplomacy and war that are surprisingly relevant today.

The first thing Chanakya stresses on is clarity of objective. That clarity can only be arrived at by unemotional appraisal and a rigorous application of mind. If we conflate this advice with the present, what it means for India is a clear understanding that we face two — not one — endemically hostile states on our northern border — Pakistan and China. Our objective must be to deal with them in a manner where our national interests are served and we can adequately protect our sovereignty and territorial integrity.

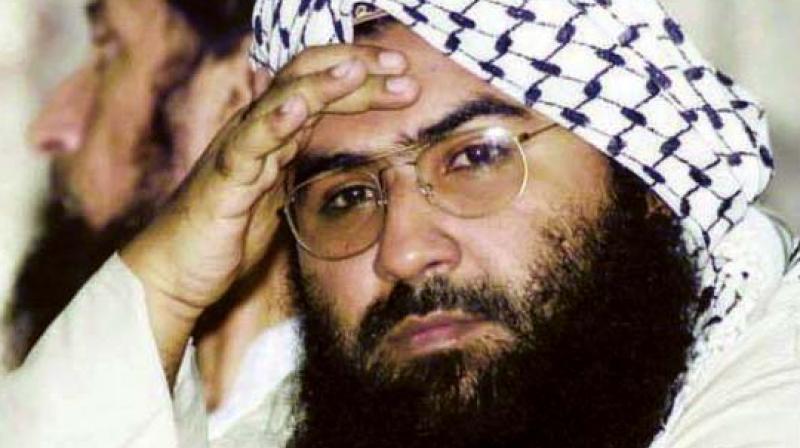

The recent veto by China on the UN’s banning of Masood Azhar, and our reaction to it, presents a good example of what is realistic appraisal. Pakistan and China are “all-weather friends”, and will unhesitatingly collude with each other against us. We should, therefore, have expected that China will not forsake Pakistan. Once this was clear, our diplomatic reaction should have been threefold. One, we should have dispensed with expending so much energy in persuading China to change its decision. Two, we should have devalued the dividends of a ban by the UN, and stressed that India is prepared to fight its battles alone in the goal to eradicate international terrorism. After all, Lashkar-e-Tayyaba chief Hafiz Saeed, has been designated an international terrorist by the UN, but roams around free in Pakistan pursuing his terrorist activities. And, third, instead of lamely expressing “disappointment” when China did use its veto, issued a bold statement condemning China for being an accessory to global terrorism.

Chanakya stated that once the objective is clearly defined, it can be pursued by several means. These means are essentially four: sama, dama, danda, bheda — reconciliation, inducement, deterrent action and subversion. There is also a lesser known fifth instrument — asana — or the strategic art of deliberately sitting on the fence. Each tactic has a definite use. All instruments can be used collectively or individually or in combination. There is never a situation of either-or. Each situation merits a careful application of the instrument(s) required.

I sometimes feel that Pakistan and China have mastered Chanakya better than we have. Pakistan uses a well-tried policy of aggression (danda) followed by appeasement (sama). This was demonstrated clearly in the Pulwama attack, and the events that followed it. First, Pakistan used the terrorist organisation, Jaish, to inflict unacceptable casualties on a CRPF convoy through a suicide bomber. Immediately thereafter, PM Imran Khan issued a conciliatory statement inviting India for talks. Pakistan is adept also in the policy of subversion (bheda). The ISI has successfully recruited local Indians to further its proxy terrorist war against India. Its covert infrastructure within India is widespread and it can activate sleeper cells at will within our borders.

China, too, is a past master in Chanakyan politics. It engages with India (sama), but never loses sight of its principal goal of containing India (danda). Only such a policy can explain the major Chinese military incursion in Chumar in Ladakh even as President Xi Jin Ping was on a state visit to India in September 2014.

Following Pulwama, our precision airstrike against Jaish terrorist bases in Balakot is a good example of the correct use of Chanakyan principles. It must be remembered that Chanakya privileged peace over war. War, he said, must be the last option, when no other means allow coexistence with dignity. In response to the magnitude of the Pulwama attack, and the ceaseless use by Pakistan of terrorism against us, restraint at any cost was not commensurate with national dignity. The airstrike on Balakot was clearly the need of the hour. But, since our aim was not war, it was good that the air strike was calibrated to be only against terrorist bases, avoiding military installations or inflicting civilian casualties.

Chanakyan politics is clear in its goal, but strategically supple. I am, therefore, surprised when I hear statements from people that India must never agree to talks with Pakistan. Any one cognisant with Chanakya’s thinking will know that talks are a means to an end, and not an end in themselves. Pakistan is a neighbour. We cannot say that we will never talk to it. What we need to understand is that talks must take place at an agenda and time of our choosing, as part of our strategic matrix, and without nullifying other instruments at our disposal to deal with Pakistan.

There is much else, too, to learn from Chanakya. He stresses on the importance of a clear line of command and control. National interest, he says, is best pursued by the deft use of diplomacy, defence preparedness, and intelligence gathering. All three are important, and no one can be a substitute for the other. Success in war and diplomacy is dependent on inner strength, which he defines as an adequate treasury, a harmonious countryside, and a strong army. He focuses, too, on the art of making and cultivating allies, and negotiating treaties. A key factor is a deep study of the workings of the enemy state. (In this context, it is a pity that the Policy Planning Division in our foreign office is more or less defunct). Good counsel (mantra) is pivotal, and the King (in current times the government) should make institutional arrangements to receive it. War, when necessary, can be of four types: war by counsel (mantra yuddha), open war (prakash yuddha), psychological war (kuta yuddha), and clandestine war (guda yuddha).

We may have taken decisive action in attacking Balakot, but often our strategic responses are reactive rather than pro-active, ad hoc, lacking in anticipation, and waffling. This is unfortunate for a nation that produced some two millennium ago a genius in statecraft like Chanakya.