How legal luminaries clashed in Indira Gandhi election case

CHENNAI: On the eve of another anniversary of the declaration of the National Emergency on the night of June 25, 1975, by the then Indira Gandhi regime, this book under review is much more than yet another version of those politically dark days in post-Independent India.

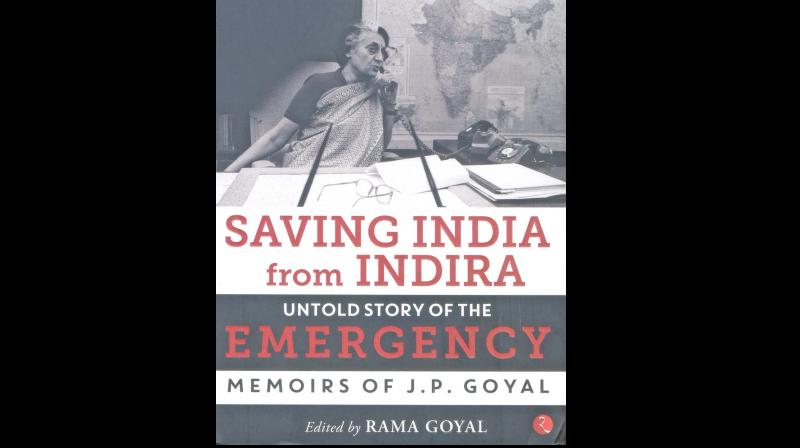

Put together by Ms Rama Goyal, daughter of one of the distinguished senior lawyers of the Supreme Court, Sri J.P. Goyal, who passed away in 2013, this highly instructive personal account of the late advocate, titled, ‘Saving India from Indira, Untold Story of The Emergency- Memoirs of J.P. Goyal’, has two equally distinguished contemporary personalities endorsing it, former Finance Minister Sri Arun Jaitley and Sir Meghnad Desai, Emeritus Professor of Economics, LSE.

Though to the outside world at large it is Sri Shanti Bhushan, later Union Law Minister in the Janata Party government led by Sri Morarji Desai, who is known as the glamorous lawyer of the Lohia socialist-in-rags Raj Narain, who had challenged and won the famous election petition against Mrs. Indira Gandhi, not many know that another equally astute lawyer hailing from U.P., J.P. Goyal, was another lawyer for Raj Narayan, who played a quiet, solid role in the legal tussle.

There were certain aspects of this historic case, which drew worldwide attention, that only J P Goyal as an “insider” was privy to; and he himself had played a key role in shaping the course the case ultimately took, both in the Allahabad High Court and later in the Supreme Court when Mrs. Gandhi’s appeal against her disqualification was admitted by Justice VR Krishna Iyer with some conditions. Goyal had written about it, yet made no effort to publish them.

But as destiny would have it, as his daughter Rama Goyal says in her preface, when she was going through her parents’ papers and other belongings in October 2017 after their demise, “I found a file of papers of my father with the label, ‘Unknown Facts Relating to the Emergency Period (1975-77).” The papers contain “material dictated by him sometime in the year 1979 and contain many hitherto publicly unknown facts related to the legal case of Raj Narain versus Indira Gandhi, the attempted review in 1975 of the Kesavananda Bharati judgment of 1973, and other legal matters and events during the Emergency of 1975-77.”

While it still intrigues Rama Goyal why her father did not choose to publish his papers then - perhaps “he did not wish to offend his colleagues as these were very sensitive cases leading up to and during the Emergency-, she now felt that it was her “duty as a citizen of this country and as Goyal’s daughter to publish these papers as a matter of historical record. If some egos are hurt, then so be it.”

For the post-Emergency generation, these would come as huge revelation, notwithstanding old timers in national politics and the legal profession knowing it in bits and parts. One major aspect of this book is that it brings out the ‘serious differences’ between two legal luminaries, the family of the Bhushans and of Sri Goyal, while handling the Indira Gandhi case, notwithstanding that both lawyers were working for Raj Narain.

Despite Raj Narain making history, first legal and then political by defeating Mrs. Gandhi in the 1977 election in Rai Bareily constituency in U.P. by a margin of 55,000-odd votes- strangely this number squares with the margin Smriti Irani of the BJP now in 2019 defeated Rahul Gandhi in Amethi-, Goyal’s account is a telling pointer how lawyers can make and unmake a case. But the ‘unity of purpose’ in this case - to unseat Indira Priyadarshini Nehru Gandhi- was big enough and the political context in the backdrop of the JP Movement too huge not to make that happen amid all the moves and counter-moves by a Prime Minister in power.

Goyal’s account candidly says had Shanti Bhushan accepted his advice, while dealing with the election case, particularly on the former taking a position not to take up arguments in the review petition filed by Mrs. Gandhi until the Emergency was lifted as taking recourse to Article 14 during the Emergency period would be futile since President’s proclamation had suspended operation of those basic articles, the course of events could have been different. It forms a very fascinating chapter in the book, details of which should be relished in its reading.

There is also the extraordinary ball-by-ball account, of how the eminent Jurist Nani Palkhivala argued before the 13-member Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court, presided by then Chief Justice A N Ray, whose appointment itself superseding three senior Judges of the Supreme court was a big controversy then. The bench was set up, writes Goyal in November 1975, “clearly with the intention to overrule the judgment in the Kesavananda Bharati case, in which by a majority decision, the Supreme court had held that the Parliament had no jurisdiction to pass a Constitution (Amendment) Act if it violated the basic structure of the Constitution.”

Had that judgment been set aside by the A. N Ray-presided bench, legal luminaries including Palkhivala felt the implications for Indian democracy would have been far more serious, but it was stopped on its tracks then and there by the historic arguments presented by Palkhivala in the Apex court. If the Kesavananda Bharti case judgment was overturned, it would have been easy to even declare a monarchy in the country, Palkhivala felt, as he conveyed his feelings to Goyal before rushing to New Delhi to appear in the Supreme Court.

“I have heard Sri Palkhivala arguing cases in the Supreme Court before and after this case. I can say that his performance in the present case was truly superlative. For one complete day, he argued as to why the Supreme Court could not sit to decide the correctness of the judgment in the Kesavananda Bharati case,” writes Goyal. As a miracle would happen, three days later, that Bench itself was dissolved. “It was a great success for us and Shri Palkhivala received thunderous applause when we came out of the courtroom. It was a great victory for the nation,” says Goyal who was part and parcel of those Apex court proceedings.

In this account there are also revealing little known details so far, those related to the role ‘interrogatories’ played when the election petition was heard in the Allahabad High court and how Goyal was diligent enough to save Raj Narain’s case. Shanti Bhushan himself had recalled in his later memoir that had not Mrs. Gandhi replied to those ‘interrogatories’, she might not have been in trouble!

Rama Goyal also spells out another reason for publishing her father’s memoir now as she felt that Shanti Bhushan son Prashant Bhushan’s account of the case in his famous book titled, ‘The Case That Shook India’, “some of the things have not been correctly or fully mentioned therein.” Thus, publishing this book became a necessity, she avers, as Goyal’s role in this very complex election petition with twists and turns, had not been explicitly acknowledged earlier. Well buttressed with legal citations and other nuanced details with notes, excerpts from sources like the unpublished ‘JP Papers’ and ‘The Emergency Files’ and from Home Ministry files in the National Archives, New Delhi, this book should help to understand the ‘gaps’ in the big picture of the Emergency days. Interesting anecdotes add spice to this account: To savour just two, Atal Bihari Vajpayee at one stage advised Raj Narain to withdraw his election case against Mrs Gandhi after the victorious war against Pakistan leading to birth of Bangladesh; second, Indira Gandhi acceding to the request of the Swatantra Party leader Piloo Mody, an architect-politician, to allow his two ‘Irish Setter dogs’ to accompany his wife to meet him in jail when he was under detention during the Emergency! A detailed set of appendix, documents from proclamation of Emergency, press censorship and so on enhance the historical value of this memoir.